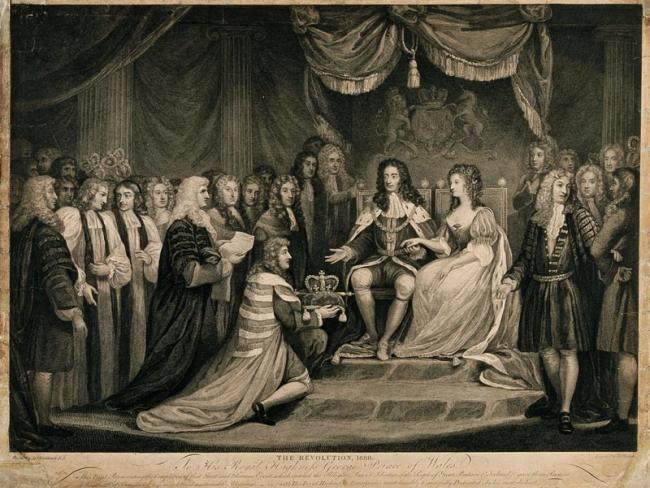

William III and Mary being presented with the crown of England. Image Wellcome Collection.

A revolution that paved the way for modern Britain is often derided as reactionary and backward looking. The opposite is true…

Revolutions are made by people. They rarely happen in a straightforward way and the results are often uncertain. The removal of James II in 1688 is such a case.

Called the “Glorious Revolution”, it is usually portrayed as a peaceful restoration of ancient liberties and a religious conflict. The alternative view is that it created a new type of state and contributed greatly to the modern world. Neither a coup d’état nor a foreign invasion, it was a popular revolution that led to ideological change.

In his book 1688: the first modern revolution Professor Steven Pincus uses original sources to show how the conflict was about who rules rather than religion. He argues that the changes brought about were truly revolutionary and positively influenced the future of England and Scotland.

After restoration of the monarchy in 1660, Charles II and later James carried on in much the same way as earlier Stuart kings. Political discontent was widespread, and not only due to the Catholic king’s lack of religious tolerance.

Support

William, Prince of Orange, invaded England in November 1688, with the encouragement of some politicians and possibly to forestall the return of an English republic. William received overwhelming support once he landed. Within a few weeks James was gone, allowed to escape into exile.

Pincus points out that “… unlike James and his advisers, the revolutionaries imagined that England would be most powerful if it encouraged political participation rather than absolutism, if it were religiously tolerant…and if it were devoted to promoting English manufactures rather than maintaining a landed empire.”

This political participation was wide and deep. The nationalist sensibility that James II challenged “…led the English to insist that ultimate political authority lay in the nation – though they disagreed whether the nation meant Parliament or the people more broadly defined.”

Allegiance was to English liberty, religion and law and not to a particular king – beliefs shared by all social classes. The transformation of the English state and society in the 20 years afterwards was only possible because of the civil wars and other ideological events in the 1640s and 1650s that transformed conceptions of state, religion, and society.

Conventional historians reduce the revolution to an anti-Catholic crusade, anti-papist versus papist. Other scholars focus on the central role played by a small group of Whig opponents of James II.

Pincus challenges both. “Both groups deny that the revolutionaries had any transformative political or social agenda. Both groups, then, depict 1688-89 as a conservative revolution, a revolution in defense of Protestantism against a Catholic king.”

‘The revolution was a long step towards a secular society…’

The revolution was not about religion, not about identity politics, unlike the Duke of Monmouth’s rebellion of 1685 which was very much anti-Catholic. It was a long step towards a more secular society, in which disputes about religion were less significant than debates about economics and politics.

For many historians the people are mere spectators of their country’s history. Pincus says that view merely follows establishment Whigs in insisting on English popular political passivity, even if they differ on whether the revolution was an aristocratic coup d’état or a foreign invasion.

In contrast he shows that the English were in reality extremely well informed about foreign affairs by the end of that century thanks to “…new institutions like the vastly expanded post office, the increasingly ubiquitous coffeehouses, and the ever proliferating committee rooms of trading companies”.

Restoration English men and women were not xenophobic. Instead they placed foreign news within sophisticated ideological frameworks. They were eager to learn about European politics because they understood it and thought it affected their lives.

In 1688 England was ripe for change. People rose up against James II’s regime across the country. It did not stop there, as Pincus recounts, “Popular uprisings, then, spread throughout England, Wales, Scotland, Ireland, and North America with bewildering rapidity in the autumn of 1688 and winter of 1689. In some cases, townspeople rose up against their governors; in others, aristocrats and gentry coordinated with their tenants and local yeomen to defy loyalist elements.” Almost half of William’s “invasion” force was British.

Activity

William’s manifesto, the Declaration of Reasons, was widely distributed. He gave supporters 3,000 copies each to put into “the hands of the generality of the nation”. The nation was active. Public debate over the nature of the revolution was contested, “[it] had spawned important changes in party polemic and English political culture. On constitutional and religious matters the political center of gravity had shifted.”

Pincus argues that the revolution and the debates were about the economy’s future as well as about the nature of the state. He cites many supporters of the revolution who put forward radical economic policies of backing industry and welfare. A result was “the rage for social legislation, ‘salutary laws for the welfare of the public’, that became possible only after the revolution.”

Ways of thinking had changed too. For the first time the nature of wealth was explained as a product of work – well before Adam Smith in the 18th century and Karl Marx in the 19th.

For example, the philosopher John Locke wrote, “if we rightly estimate things as they come to our use, and cast up the several expenses about them, what in them is purely owing to nature, and what to labour, we shall find that in most of them 99/100 are wholly to be put on the account of labour.” Many others expressed the same idea.

Pincus claims that the revolution of 1688-89 was a bourgeois revolution in a cultural and political sense. It “…represented the victory of those who supported manufacturing, urban culture, and the possibilities of unlimited economic growth based on the creative potential of human labor.”

Marx considered that the Glorious Revolution was “the first decisive victory of the bourgeoisie over the feudal aristocracy”. This book helps us to understand more about how that happened and the impact on our nation.

1688: the first modern revolution, by Steven Pincus, is published by Yale University Press.