An 1843 painting glorifying the destruction by British naval vessels of Chinese war junks in Anson’s Bay in 1841

The Opium Wars against China in the mid-nineteenth century were the nasty climax to a most disgraceful chapter in the history of the British Empire…

Extracted from poppies, opium is a highly addictive drug, though it can serve as a medicine. By the end of the 17th century, non-medicinal drug use of opium had appeared in China, particularly around the port of Canton (now know as Guangzhou), where most foreign merchants traded. In the mid-18th century the British East India Company had secured trading rights for opium after gaining control of Bengal from the Moghul emperors. Profits from opium exports were to help the British Empire pay for spices from the East Indies. For traders, a supply of addicted consumers meant a business boom.

Though the emperors of China were worried about the spread of foreign influence, they were also desperate for revenue. Foreign merchants were tolerated, as they bought Chinese tea and silk, though their movements were strictly controlled. They were allowed to settle in Macao, a Portuguese settlement since the 16th century. With Portugal’s decline as a maritime power, the East India Company became dominant there.

Banned

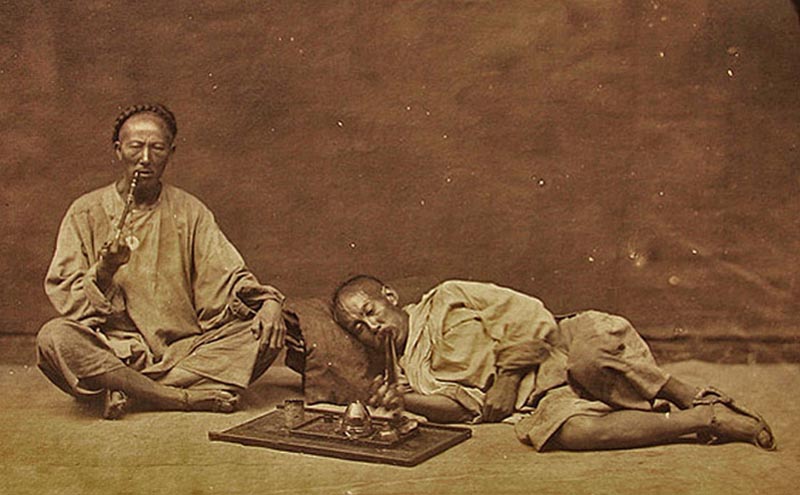

The spread of opium-smoking eventually disturbed the Imperial Court in Beijing. In 1729 an edict banned opium smoking and its importation, except under licence for medicinal use. There were heavy penalties for dealing in the drug. Initially the East India Company kept to the ban, not wanting to jeopardise its influence, and opium smokers in China were limited to supplies from the Portuguese or freebooters.

The Chinese increased controls on opium throughout the 18th century. To evade the ban, the East India Company farmed out transport to “country ships”, private traders whom the company licensed to take goods from India to China. It did not risk sending opium in its own ships for fear of losing its lucrative tea trade.

‘The British Empire used the profits of the opium trade to pay for Chinese products.’

Opium was grown by poppy cultivators in India, especially in Bengal, effectively under British control like most of India at the time. To bring the opium into China, the country traders sold it to smugglers along the Chinese coast. The gold and silver the traders received from these sales were then turned over to the East India Company.

In China, the East India Company used the gold and silver it received from opium smuggling to purchase goods that could be sold profitably in England. There was tremendous demand in Britain for Chinese tea, silks, and porcelain pottery, but there was little demand in China for Britain's manufactured goods.

As Britain did not have enough silver to trade with the Chinese Empire, the British Empire used the profits of the opium trade to pay for Chinese products.

The amount of opium imported into China at first increased gradually from approximately 200 chests a year in 1729 (about 12 tons) to 1,000 chests in 1767, before surging to 10,000 a year between 1820 and 1830. By 1838 the amount had soared to 40,000 chests, over 2,500 tons of opium extract.

For the first time the balance of payments began to run against China and in favour of Britain. Such a massive network of opium distribution had formed, that by the 1830s millions of Chinese were hooked. This caused significant damage to the health and productivity of the nation. At this point the British Empire decided to force the issue of increased trade rights, stressing the opium trade.

The Qing ruling dynasty attempted to enforce tighter opium restrictions. In spring 1839 Chinese authorities at Canton confiscated and burned the opium. In retaliation, the British occupied positions around the city. This trading conflict escalated into the first Opium War between Britain and China from 1839 to 1842. During the war the Chinese could not match the technological and tactical superiority of the British forces. A British naval fleet arrived in June 1840, attacking along the Chinese coast.

The outcome of this war was not to legalise the opium trade but it halted Chinese efforts to stop it. In 1842 China agreed to the Treaty of Nanking and had to pay a large fine. Hong Kong island was ceded to Britain. Five other ports, including Canton, were opened to British residence and trade.

Imports

In the second Opium War (1856–60), the Chinese government was again defeated by the British and the French. This time it was forced to legalise the opium trade, though it did levy a small import tax. Opium imports to China had reached 50,000 to 60,000 chests a year, continuing to increase for the next 30 years.

The peace was as wicked as the war. With the Treaty of Tientsin (1858), China had to open 11 more ports to trading and allow foreign ships including warships to navigate freely along the coast and up the Yangtze River. The British were given trading rights in the ports of Canton and Shanghai and in 1860 more land to extend the Hong Kong colony.

Foreigners were allowed to travel to the interior for the first time. Christians gained the right to spread their faith and hold property, thus opening up another means of western penetration. China's right to rule in its own territory was increasingly limited. The Chinese refer to this period as the time of unequal treaties – one of national degradation and humiliation.

The importance of opium in the West's trade with China declined from the beginning of the 20th century. China also signed a treaty with India to end the import of opium by 1917. But opium smoking and addiction remained a problem for China in subsequent decades. Opium smoking was not finally eradicated until after the accession of New China led by communists in 1949.