25 February 2017

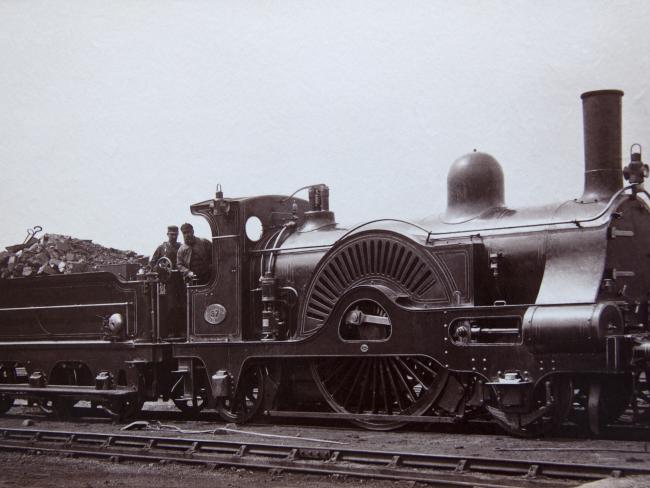

Caledonian Railway locomotive of the late 19th Century. Photo Tony Hisgett via Wikimedia Commons [CC BY 2.0]

Our working class grew in strength by pursuing its class interests of improving wages and work conditions within the framework of Britain. Here we look at three struggles from the late nineteenth century.

Since the birth of industrial capitalism, a web of industrial sinews has held the constituent regions of Britain together. The recent dismembering of much of that web has brought not only economic collapse to regions but also threatened our national integrity. We recount struggles in Scotland, London and North Wales that pursued essential class goals of improving wages and conditions of work.

RAILWAYS IN SCOTLAND

During the 1880s railway workers in Scotland worked long hours for companies that expected employees to do as they were told. Disputes in 1883 resulted in some nominal concessions, followed by a period of relative peace. In January 1890 the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants in Scotland (ASRS) started negotiations with the North British Railway Company to reduce working hours and excessive spells of duty.

The company offered an eight hour day but only to those in the signal cabins. The remaining 94 per cent of employees would continue to work at least twelve hours a day, some for fourteen or fifteen hours. This concession was unacceptable. After members’ meetings in August and September, the society made a number of demands, including a maximum ten-hour day for all grades of work with an eight-hour day in intensive parts of the network.

The railway companies did not wish to acknowledge the union; they only wanted to discuss grievances with grade deputations. That had had already proved inadequate, not least because of victimisation. In mid-October the ASRS announced they would consider a strike if the companies rejected an offer of arbitration.

Cessation of labour

On 23 November the ASRS executive recommended “cessation of labour” following mass meetings in Glasgow and elsewhere. It asked members to send notices of resignation to the society prior to transmission to the railway companies. The executive thought action would be justified if it received sufficient notices.

The executive fixed 24 December as the date all work would cease, so long as there was enough support. Society members in Glasgow and Edinburgh were enthusiastic for a strike, but those in the country districts were more apathetic. In early December the executive considered that the number of notices received did not warrant a cessation of labour.

Throughout December mass meetings of members were held in Glasgow, Motherwell, Perth and elsewhere, debating whether or not to strike, with or without prior notice. The executive urged delay, but most of the meetings voted to strike immediately, risking illegality for a strategic advantage.

Surprise

By 21 December 3,000 men were on strike; by Christmas Day 8,500. The railway companies were completely taken by surprise. Transport in the central, eastern, southern, and western districts of Scotland was utterly paralysed. The strike was most heavily felt by the North British Railway which had the worst conditions, less so by the Caledonian Railway and the Glasgow and South-Western Railway.

The effects were widespread. Passenger train time-tables were reduced. Rail depots were blocked for at least four weeks with goods and unmanned engines idle in sheds. Despite the influx of some blacklegs, for several weeks the companies could do little to move goods and minerals. Chiefly there was a lack of coal: stocks in Glasgow were soon exhausted.

‘Pickets were dispatched direct from meetings to bring the men out.’

Picketing was an important tactic in the previous year’s dockers’ strike (see below), so too in the Scottish railway struggle. Pickets on day one were despatched direct from meetings to districts around Glasgow and to Motherwell to “bring the men out”. The picketing of the first Sunday was a great success and men joined in shoals. Later picketing was drearier, spent at night on the hillsides of the Lothians, tramping across the moors from signal cabin to cabin, or on the road at Polmadie watching the Caledonian Railway Depot. Picketing captains carried copies of the Conspiracy Act in their pockets to restrict police officers.

Many society members struck without notice, as they felt that giving notice of resignation meant permanent severance. They believed they would be liable only to the usual penalties for absence without leave. Their hope was that the strike would only last a week, at the end of which they would return to their work with some gains. There seems to have been little concern about being held legally liable for breach of contract, although the executive had warned about that.

The North British Railway Company of course saw the action as breach of contract. It took legal action against the ASRS executive, claiming £20,000 damages for assisting strikers to break their engagements and leave the company's service without legal notice. Withdrawal of this action was one of the conditions of the later settlement.

Evictions

On the 5 January 1891, the county sheriff organised a large military and police force to evict a dozen railway-striker families at Motherwell from houses belonging to the Caledonian Railway Company. Some 20,000 people emerged to protest and there was damage to the station and a signal box. The Riot Act was read, but the authorities did force the railway company to stop the eviction of the remainder of the striker-tenants.

In mid-January there were efforts to get a compromise on the basis of the settlement between the North Eastern Railway Company and their employees. On 19 January, the ASRS executive asked the Earl of Aberdeen to use his influence to bring the struggle to an end. After conferring with the companies, he wrote cautiously to the executive pointing out that they had already amply vindicated their claims to have their grievances considered seriously, and that they ought at once to return to work.

On 28 January a deputation of strikers met the North British manager. He declared that the strike grievances would be discussed within a fortnight by delegates of the employees and the director. As many of the men on strike as possible were to be re-engaged; all prosecutions were to be abandoned and the action against the executive was to be withdrawn. The strikers accepted this compromise, and the strike was over.

On the same day a similar deputation of Caledonian Railway employees met their manager who refused to accept the North British Railway Company memorandum; they remained on strike. On 31 January negotiations were renewed, and the strike finally ended. Eventually Scotland ASRS became part of the National Union of Railwaymen, a forerunner of the RMT.

THE LONDON DOCKS

In the 1880s London was the greatest port in the world. Dock workers fell into two distinct groups. A relatively small number of workers had higher pay and some degree of job security. These included stevedores, more skilled loaders of cargo on ships, who were already unionised, and lightermen, loaders and pilots of the Thames barges that shuttled cargo around the docks. Alongside them worked large numbers of casual labourers who lifted and unloaded cargo from ships, or hauled and stacked goods into warehouses.

Usually men were too old at forty for the repetitive, hard, physical work of a casual labourer. Worse, most were hired day-to-day for a mere pittance of a wage. Foremen could take on casuals for as little as half an hour at a time. Pay was unpredictable as it depended on weather, tides, and cargoes. Even when work was regular, wages were not enough to stay out of poverty. Casuals would tramp the docks for hours, seeking work from foremen.

Men were herded into the “cage”: an iron-barred shed, outside which a contractor or foreman would walk up and down with the air of a dealer in a cattle market. They would pick and choose from a crowd of men, who, in their eagerness to obtain employment, might trample each other underfoot, and fight like beasts for the possession of a ticket for a day’s or a few hours’ work at no more than sixpence an hour.

‘A day without work meant being unable to find the necessities of life.’

Tens of thousands of casual labourers lived close-packed in rows of streets around the London docks in places like Poplar, East Ham and Rotherhithe. A day without work meant being unable to find the necessities of life. In 1887 the Medical Officer of Health for Bermondsey reported child deaths from many deficiency diseases including “want of breast milk”, rickets (vitamin D deficiency), “atrophy, debility or wasting” (likely related to malnutrition) as well as starvation and severe malnutrition.

Breaking point

In July 1888, matchworkers at Bryant & May in East London – mostly young women, similarly poorly-paid, similarly unskilled – went on strike for two weeks to draw attention to their appalling working conditions. Their noisy pickets and public marches were a success. The newly-formed Union of Women Matchworkers was the first female union in the country. Bryant & May’s workers lived cheek-by-jowl with the dockers. Their success proved that unskilled workers could improve their working conditions by providing a determined, organised front to management.

By the summer of 1889, the dock labourers had reached breaking point. The Great Dock Strike started in West India Dock on 12 August 1889, after the gang and the dock superintendent clashed over the amount of bonus money due for unloading the Lady Armstrong. Never before had these casual workers stood together. The strikers demanded a base pay rise – the famous “Docker’s Tanner” – overtime pay and a minimum employment period of four hours.

The employers were shocked by the casual workers and tried everything to impede the struggle. But on 16 August 10,000 men marched round the docks. Two days later the stevedores, who had no immediate grievance of their own, joined the strike followed by the lightermen and the men at Surrey Docks on 20 August. The struggle covered the whole port. At its height probably 100,000 workers were involved including 15,000 pickets and picket foremen who aimed to patrol the rivers, police the railway stations to deter blacklegs and control the docks.

Sympathy

There were almost daily marches. On 24 August, the largest procession, from Poplar Town Hall to the City of London, captured the sympathy of the capital – as well as much-needed funds for welfare relief. By the end of the month, The Times noted that London’s overseas trade was totally paralysed. The dock owners meant to starve the strikers into submission. But £30,000 relief sent from Australia at the prompting of the Australian dockworkers’ union allowed the strike to continue into September.

Butler’s Wharf in Bermondsey began independent negotiations with the strikers late in August and an overall agreement was reached on 14 September 1889. All the strikers’ pay and time demands were met and the contract system was abolished. The Great Dock Strike showed what an impact a united working-class community could achieve and stimulated union recruitment of dock labourers at other ports up and down the country.

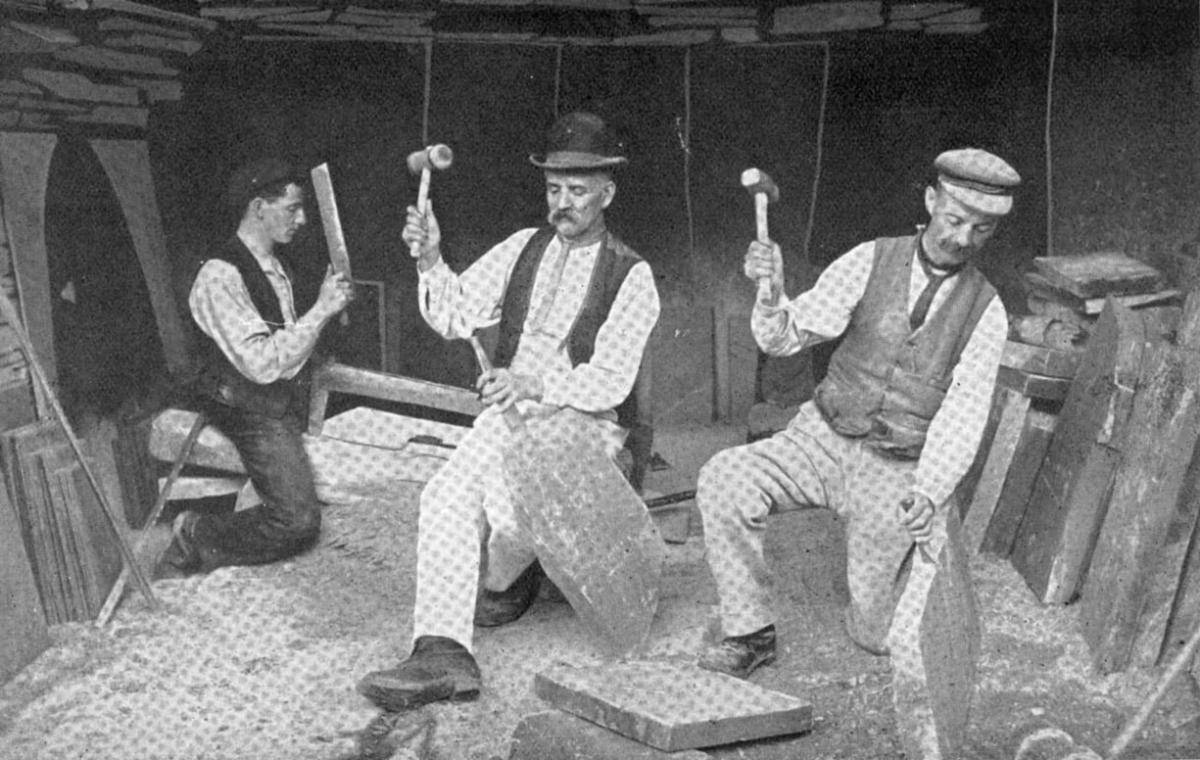

THE WELSH QUARRIES

In the 19th century around Gwynedd in north Wales, slate quarry workers endured harsh conditions. Life expectancy was short – in 1875 just over 37 years for someone in the Blaenau Ffestiniog slate mine. Yet quarry mining was a skilful occupation taking many years to learn, giving workers a large say in how they worked. Initially quarry workers haggled over the costing of extracting different qualities of slate, seeing themselves as independent contractors rather than employed workers on a wage.

In 1874 the North Wales Quarrymen's Union was established and came under immediate attack from the employers. Workers at one mine after another were given the choice between repudiating the union or losing their jobs. This culminated in lock-outs at the two biggest quarries, Dinorwic and Bethesda, owned by landlord-capitalists including Lord Penrhyn. In Dinorwic the lockout lasted five weeks. But at Bethesda the men drew up their own demands and won an increase in wages and the replacement of the quarry management. The union won further wage increases and decreases in hours over the next few years.

Downturn

In 1879 an economic downturn ended twenty years of growth in quarry production. The union faced its first major test as management brought in wage cuts. The downturn led to a long depression and wages did not increase. In 1885-86 management locked out the Dinorwic quarrymen until they accepted new conditions curtailing holidays, with wage cuts and redundancies.

A mass meeting of 3,000 men burned pro-Penrhyn newspapers and declared a strike. After trying to re-open the quarry several times without one of the locked-out men returning, management still managed to win a victory once the union ran out of funds and had to stop dispute pay.

A lock-out at Penrhyn Quarry in 1896-97 began over the men being refused leave to attend a Labour Day demonstration in Blaenau Ffestiniog. Over 2,500 stayed away from work anyway and were subsequently suspended for two days.

After this attack on their conditions, they drew up demands for time-off and a wage increase, which management rejected. Although the quarry workers agreed to take strike action in the spring, management provoked an earlier strike in November by sacking 74 leading union members.

The strike-cum-lockout lasted until the following August, supported by from trade unions across Britain. Like Dinorwic, there were several occasions when management tried to re-open the quarry. Again no workers went back, though many found work elsewhere. But the union leadership negotiated a deal that effectively meant de-recognition of the workers committee as the voice of workers at that quarry, without their knowledge. The main leaders of the quarry workers committee then took over the union leadership at a special conference.

‘Management provoked an earlier strike by sacking leading union members.’

In November 1900 new tensions built at the Penrhyn Quarry over the extension of contracting out, which meant the quarrymen would work for a contractor instead of arranging their own bargains. This led to assaults on contractors seeking speedier production at the Ponc Ffridd bank. 26 quarrymen, prosecuted for attacking the contractors, were suspended from work for a fortnight. When the matter came to court in November, the Penrhyn quarrymen marched to Bangor to support the accused, 20 of whom were found not guilty of the charges.

Ultimatum

The suspended quarrymen returned to work on 19 November, but eight banks had been closed, leaving 800 men without work. On 22 November, 2,000 quarrymen refused to work until the other 800 were able to do so too. Management issued an ultimatum: “Go on working or leave the quarry quietly”. Every one of the 2,000 quarrymen left the quarry beginning the Great Strike (or Lockout) of Penrhyn that lasted three years. On 22 December, new terms were offered to the quarrymen: 1,707 refused, 77 accepted.

As union funds for strike pay were inadequate, there was a great deal of hardship among the 2,800 workers. The quarry reopened in June 1901; about 500 men returned to work, castigated as “traitors” by the remainder. The names of those who had broken the strike were published in local newspapers. Cards with “Nid oes Bradwr yn y ty hwn” (“No traitor in this house”) appeared in strikers’ windows in the Bethesda area. Taking a card from the window was a sign that a worker had returned to work. By June 1902, 700 men had returned to the quarry and another 2,000 moved from the area, most going to work in the coalfields of south Wales, where they helped develop the mineworkers’ union which eventually became the NUM.

In September 1903 General Federation of Trade Unions, set up by the TUC to support affiliated unions in struggle, stopped paying strike pay in a period of economic recession. In November a mass meeting decided by a small majority to return to work on management terms. Men considered to have been prominent in the union were not re-employed, and many who had left the area to seek work did not return. The dispute left a legacy of bitterness and tensions for many decades. The Penrhyn quarry business, unwilling to allow dignity to its workers, never really recovered either. Its earlier fortune, based on slave labour in Jamaica, had been used to build a mock castle now owned by the National Trust.

A shorter version of this article was published in Workers March/April 2017 edition.