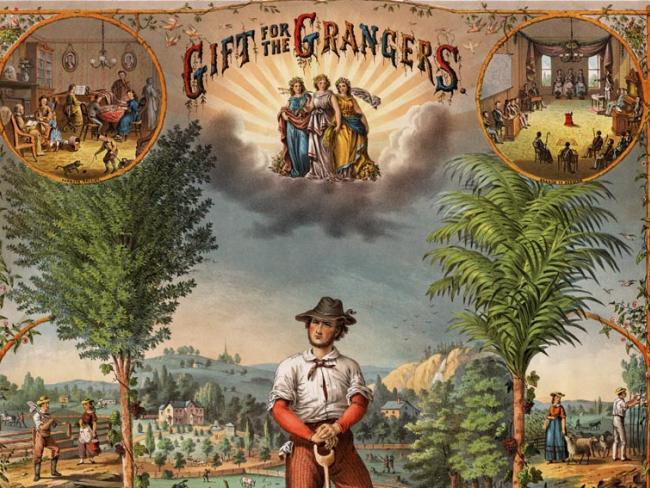

Promotional poster for the Grangers from around 1873.

Anything outside the norm that attracts support from the people but is feared by vested interests is likely to be labelled “populist”. What does it mean?

In the late nineteenth century a movement calling itself populist played a significant positive role in the history of the USA. A new political term was born. But “populism” is now widely used as a term of abuse.

The word comes from the Latin word for people, populus. It was the P in the Roman logo SPQR, the Senate and People of Rome. Romans were proud of that as it proclaimed the original idea of Roman democracy arising from the people.

America was in political turmoil after the end of the Civil War in 1865. Capitalism was rampant and the impoverishment of farmers extreme. Political parties represented only the interests of capitalists and big landlords, including the defeated slave owners.

No one spoke for the homesteaders in the west or the poor white agricultural workers in the south. Like the freed slaves, those workers were trapped in a share-cropping system controlled by landowners. And of course no one spoke for the rapidly growing ranks of industrial workers.

Farmers and workers on the land struggled to survive on the newly cultivated land of the midwest and in the south. Crop prices fell as output rose and boom turned to bust. Railroad barons grew rich by cheating farmers, using monopoly to extort high rates for taking their goods to market. Farmers grew indebted to the banks, especially when crops failed. Mary E Lease, mocked in the press as the “Kansas Pythoness”, urged farmers to “raise less corn and more Hell.”

Farmers organised alliances such as the Granger movement in the midwest, to fight railroads and banks. They demanded laws to control the railroads and end the gold standard introduced in 1873. That move had abolished silver money and forced farmers to repay their debts with dearer money backed by gold.

‘No one spoke for the homesteaders or the poor white agricultural workers.’

The lack of democracy hampered the farmers’ efforts, so they argued for political reforms such as the direct election of US senators to replace selection by state legislatures. They demanded the right to be heeded in the state legislature when they raised an issue (called the “initiative”) and to hold a referendum on it. They also wanted the power to recall any elected official before the end of their term, and the introduction of secret ballots.

But it was difficult to build unity among the different farmers’ organisations – in particular in the south. Freed slaves were not welcome in the white farmers’ alliances and had to organise separate “colored farmers” organisations.

The demand for monetary reform led to the formation of political parties such as the Greenback Party, which called for money not backed by gold as an answer to economic crisis. It ran candidates for president in 1876, 1880 and 1884, and prompted a widening debate. Then in 1891 the People’s (or Populist) Party was formed, demanding silver money, a graduated income tax, and the democratic political reforms advocated by the farmers’ alliances.

Angry

James Weaver ran for president on the Populist ticket in 1892, polling over a million votes. When the financial crisis of 1893 hit, the normally Democrat voters in the south and midwest were angry and drawn to the Populist programme, so the Democratic Party adopted it – in part – focusing on monetary reform and getting financial support from silver mining interests. It had a great orator in William Jennings Bryan, Democratic presidential candidate in 1896.

The wealthy north-eastern capitalist establishment swung into action to oppose Bryan, running a heavily financed campaign based on fear. Free coinage of silver would ruin America, they said. The populist Democrats lacked support among industrial and urban workers; the capitalists played on their fears for the value of their wages.

Despite Bryan’s oratory and a famous whistle-stop campaign, he lost to William McKinley. The economy was turning from bust to boom, and farm prices were slowly rising. The discovery of gold in California and Alaska ended its scarcity, lowering the value of the gold-backed currency.

Hijacked by the silver lobby, populism declined rapidly after 1896. And despite some links between farmers and organised workers, it lacked a long-term strategy for all workers. Meanwhile Presidents William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt focused on conquest and expansion, leading to the Spanish-American War of 1898 and other colonialist adventures.

Yet populist ideas about extending democracy had gained currency, and many were eventually adopted. Later legislation introduced the direct election of senators, citizens’ three rights of “initiative”, referendum and recall, the secret ballot and graduated income tax.

Populist ideas also formed an important part of the reform agenda during the following period, called the era of “Progressivism”. The banks were reformed and anti-trust legislation was passed during the presidency of Woodrow Wilson (1913 to 1920).

Later Franklin Roosevelt directly tackled the Great Depression. He aimed to relieve the distress of working people through the New Deal. From fighting it tooth and nail, the US capitalist establishment had tamed populism by adopting, if not its spirit, most of its programme.