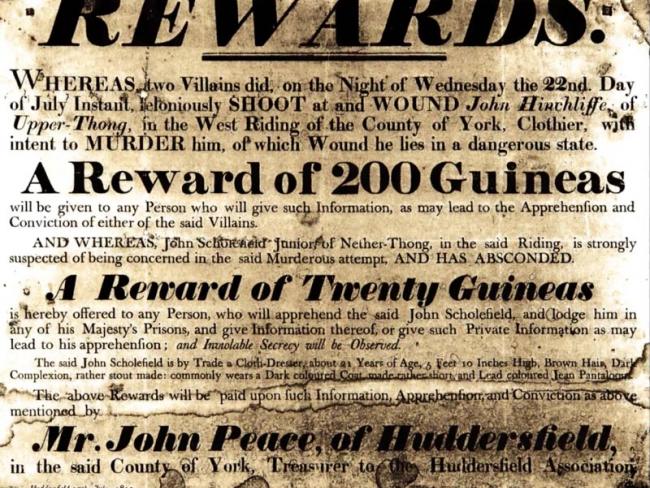

The crackdown on Luddites relied on troops, huge rewards and police informers. Many accused were acquitted because juries felt they could not rely on the honesty of police witnesses.

The British working class was the first proletariat in the world to emerge out of the land. It had to make a stand or go under…

Working class organisation has a long history in our land. Trade unions have existed in Britain for well over three centuries, working to maintain or improve working conditions for wage-earners. Can we take anything useful from this lengthy experience for application to current times, or is the past redundant?

Recognisable trade unions appeared in the latter part of the seventeenth century. There were some collective combinations and approaches evident even before then. These cannot really be seen as forerunners of trade unionism for many were within guild frameworks. But demonstrably some people did come together and act collectively to determine aspects of their working lives.

Common interests

In both medieval and early modern times, working people asserted their common interests, at times quite successfully. Glimpses of them appear as inverted praise in the historical records. In 1383 the Corporation of the City of London prohibited all “congregations, covins and conspiracies of workmen”. In 1387 the serving-men of the London cordwainers (shoemakers) were in rebellion against the “overseers of the trade” and made a fraternity.

In 1406 the serving-men of the saddlers asserted that they had a fraternity for “time out of mind”, which the masters declared was out to raise wages. In 1538 the Bishop of Ely reported to Thomas Cromwell that twenty-one journeymen shoemakers of Wisbech had assembled on a hill outside the town and demanded the master shoemakers meet them about an advance in their wages.

‘The unions never began nationally in Britain, nor were they imposed from outside.’

Particularly admirable were the stonemasons. They had a history of congregations and confederacies, which were expressly prohibited by Act of Parliament in 1425. It is probable that the masons, wandering over the country from one job to another particularly on cathedrals and churches were united, not just in any local guild, but in a trade fraternity of some extent. Certainly stonemasons were among the earliest expert practitioners of demarcation disputes and restrictive practices.

Journeymen, skilled manual workers, moved from place to place carrying a bag of tools and, because of their degree of skill, were sought after. The extent should not be overestimated, but it seems that in certain cases journeymen fraternities existed within the craft guilds of the Middle Ages, acting to further the interests of their own members.

This occasionally extended to strikes either against the employers or against the authority of the guild. Many established long-lived combinations, some of which could only be put down by new laws, and had alms-boxes to help members’ families that were in distress.

The guilds were run by master craftsmen employing journeymen and labourers, and there were journeymen who wished to become a master too. So the guilds were not the equivalent of a trade union. Yet they were also about protecting the quality of craft work by ensuring that only those with the necessary expertise could participate in the craft. They aimed to preserve those features of regulation which craftsmen had long recognised as “giving them protection from the cold blast of an unregulated market.” Today’s trade unions still need to protect workers’ professionalism from the same undermining market.

Skilled artisans

The trade unions in the 17th and early 18th centuries did not generally emerge as a product of the factory system. Rather they came from skilled artisans: shoe-makers, cabinet-makers, tailors, building workers, weavers and so on.

These workers operated usually in small workshops or even from their own home. Long before the industrial revolution, property-less people – having only labour power to sell – were coming together no matter how small or few in number.

Accordingly, the unions never began nationally in Britain, nor were they imposed from outside. They all started locally in parish, village, or town, then spread wider. Generally the first combinations of workers were formed around a skill or a community of similar jobs, based on their capacity to fight, which gave them potential strength and a greater advantage than those who were unable to argue or bargain directly at all.

Early British trade unionism was a self-generated product of the workers involved, acting alone without external union organisers, do-gooders or political parties. The original unions didn’t have grandiose notions or even call themselves national. They tended to have prosaic names like “Steam Engine Makers”. Members worked at the trade, and when they got big enough employed a secretary.

The condition of the growth of these unions was based on an absolute suspicion of anyone who didn’t make steam engines (or whatever) and didn’t go to work every day in the trade.

The unions were born and developed in conspiracy against the employers and the employers’ government. Trade unionism in engineering first emerged in the 1780s when a Friendly Society of Mechanics was established in Bolton, Blackburn and Chorley.

By 1799 employers in London asked Parliament to make it illegal for millwrights and engineers to combine, which resulted in the passing of the Combination Acts in 1799 and 1800.

Running through all the approach of these unions is that only those who work shall control. It was true of the boilermakers, shipwrights, wainwrights and the rest. The main questions for these craft unions were “who controls?” and “who runs the union?” There was suspicion of those who did not work at the trade, who were not out of their ranks.

• In the next issue we will trace the path of our trade unions from emergence into legality in the early 19th century to the present day.