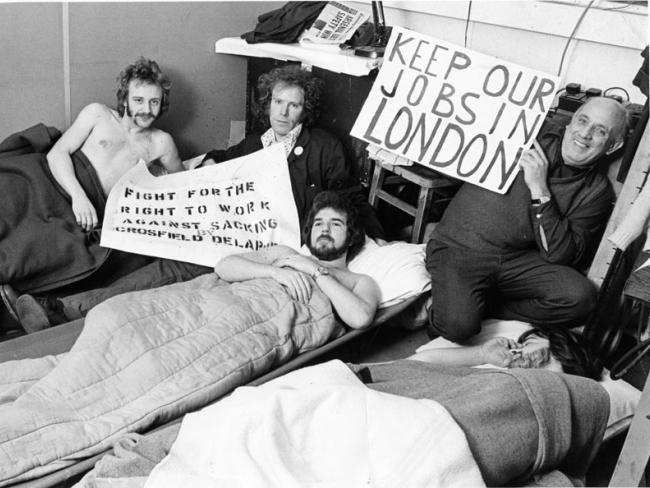

Crosfields factory occupation, London, 1975. Redundancy payments legislation was aimed at heading off struggle for the right to work.

History shows that when we rely slavishly on legislation our aspirations for advance have subsided, along with our organisation…

The British working class makes gains and improvements when it has a striving, self-reliant mentality and applies its collective strength to solve problems. Conversely, when we rely slavishly on legislation our aspirations for advance have subsided, along with our organisation. Capitalist legislation about work is designed to block or side-track our progress. It will not lead us to the Promised Land.

Here are some examples. There are many others.

Our class used to employ its collective strength at work to defend, or occasionally expand, the number of jobs. In 1965 the Labour government introduced the Redundancy Payments Act. This aimed to prevent struggle to protect employment levels, and tempted workers with “fool’s gold”. The Labour government of the late 1970s continued the same stratagem, using social democracy and apparently benevolent legislation to neutralise working class struggle for both jobs and pay.

Unimpeded

Since then redundancies and closures have proceeded largely unimpeded. Our class has rarely contested decline and argued for greater employment or campaigned for proper apprenticeships for the young. In 1981 Thatcher implemented the EU Acquired Rights Directive with the Transfer of Undertakings (Protection of Employment) Regulations Act (TUPE). This claimed to protect people whose work units had been sold or handed to another employer. In reality it undercut workers’ resistance and enabled large-scale privatisation.

British trade unions made huge strides forward to gain paid holidays for millions of workers between 1918 and 1939, despite economic recession. It was the biggest industrial reform since the introduction of the eight-hour day and resulted from well-organised struggle, asserting the interests of labour over capital. (The May/June 2017 edition of Workers has a fuller account.)

Organised labour discussed and publicised the demand at all levels. It was high on the agenda in workplace negotiations and official representation and when necessary was pursued by direct action. Holidays with pay were secured mainly through voluntary collective agreements between employers and workers and not the 1938 Holidays with Pay Act of 1938, which covered only a minority of Britain’s workforce.

Some unions regarded legal provisions on holidays with suspicion “as a window-dressing stunt to be produced at election time”. British trade unions at the time still preferred collective bargaining to waiting for state legislation.

‘Many trade unionists have become wedded to legislation.’

Workers’ attitudes to pay in recent decades show the same pattern as to redundancies. Many trade unionists have become wedded to legislation for the “minimum wage” or the slightly higher “living wage”. In reality, to live with more dignity workers on low wages need better union organisation on the ground to achieve the major breakthrough to higher wages.

Poverty wages

A national minimum or living wage implies an acceptance of poverty wages, perpetuated through state benefits. Workers and many unions have failed to fight for better wages; tax credits and housing benefits have become a lifeline for far too many people on low pay.

Labour Chancellor Gordon Brown introduced tax credits in 1999, which effectively shored up poverty wages and discouraged wages struggles. Workers receive pay so low that they can’t live on it or raise a family. Rather than fighting in a trade union together to force the employer to raise wages high enough to live on, workers claim a top-up in the form of working tax credit.

One set of workers pays another set of workers to make it possible for them to work for a wage which is so low they can’t survive on it. That’s brilliant for employers, but bad for our class in many ways. We must re-learn how to fight for the dignity of a decent wage!

Workers in Britain and elsewhere have fought for centuries to reduce working hours and limit the working day. Contrary to propaganda, this didn’t start with the EU Working Time Directive, which has been followed by deterioration. The number of hours people are working is climbing steadily. So too is the amount of unpaid overtime, particularly in monthly-paid jobs.

In almost every workplace we have lost control of the hours that we work. Rather than resist and assert ourselves, we tail behind what capitalism permits. Employers make collective action among workers more difficult by using home-based workers, zero-hours contracts, agency workers, internships and so on.

Promoting division

Employers actively promote division between employees and generate competition between workers. Our trade unions need to get back in contact with people at work and attempt to rebuild collective identities and workplace unity in these worsened conditions. It won’t be easy but it must be done.

It is a similar story with agency work. The EU’s Agency Workers Directive hasn’t protected anyone except employers. It has encouraged and normalised a massive growth in casualisation. Employers seek to escape from employment rights and to evade tax and national insurance. Workers mostly acquiesce.

The Agency Workers Regulations came into force in October 2011, implementing the EU Temporary Agency Work Directive. But this doesn’t assure agency workers the right to equal treatment on their basic terms and conditions of employment. The only way to enforce that parity is through workplace organisation and not through the courts.

Unions need to ensure that people working in the same roles, alongside one another, are given the same rewards for doing the same work. One step would be to stop employers from using employment agencies or fake “self-employment” as a cheap alternative to employing workers on permanent contracts.

Recourse to legislation appears to be the only cut and dried response. But this lazy thinking proscribes any other way to determine a better solution. To progress as a class, we must revert to pressing our needs and claims with good collective organisation.