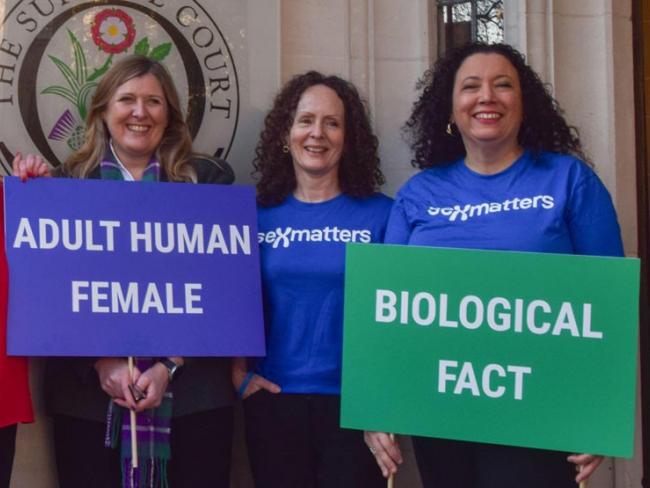

Campaigners from Sex Matters and For Women Scotland outside the Supreme Court, November 2024. Photo Vuk Valcic /Alamy Stock Photo.

When women’s rights in Scotland were sacrificed in the name of “progress”, Scottish women decided to fight back. A new book tells their story…

The women who wouldn’t wheesht: voices from the front-line of Scotland’s battle for women’s rights, edited by Susan Dalgety and Lucy Hunter Blackburn, hardback, 384 pages, ISBN 978-1408720707, Constable, 2024, £22. Kindle and eBook editions available. Paperback edition due out March 2025.

This fine book (“wheesht’ means “hush’ or “be quiet’) presents voices from the unprecedented five-year campaign by a large number of Scottish women who were determined to stop what they correctly saw as an assault on their rights. Their struggle helped to oust Nicola Sturgeon, Scotland’s first minister who, at the height of her powers and with an iron grip on her party, unexpectedly resigned.

By 2018, organisations like Stonewall were promoting what they called a new “trans umbrella”. It covered men who had made no change whatsoever to their bodies, but demanded to be called women and to get access to spaces where women were vulnerable, such as changing rooms and shelters, and to have access to jobs delivering intimate care to young, elderly or disabled women, normally reserved for women workers.

In 2022 the SNP/Green alliance introduced the Gender Recognition Reform (Scotland) Bill. It was designed to remove any medical requirement for legal gender recognition and change the basis to one of self-declaration. But if self-declaration of gender had become law in one part of Britain, women’s sex-based rights and the very definition of female in language, policy and law would have been diminished across the country.

In 2004 Holyrood had agreed that the interaction between central and devolved government meant that the original Gender Recognition Act of 2004 was best handled in Westminster. On 16 January 2023, the Secretary of State for Scotland, Alister Jack, invoked the 1998 Scotland Act to block the attempt to introduce separate gender recognition rules in Scotland because it would adversely impact on the operation of equalities legislation throughout Britain. Campaigners had warned from 2018 and earlier about a potential clash with the Equality Act 2010.

While the editors of the book write that “Jack deserves credit for having the political courage to use a Section 35 order to act”, they also point out that it was grassroots campaigning in Scotland that laid the ground for this action, which was acknowledged even by the government’s equalities minister at the time.

On 30 January 2023, Sturgeon tied herself in knots in an ITV interview after double rapist Adam Graham/Isla Bryson had been initially sent to a women’s prison. At a press conference on 6 February, Sturgeon referred to the double rapist as “her”. She resigned on 15 February.

Woman’s Place UK stresses the importance of distinguishing sex from gender. An individual’s biological sex is an immutable characteristic. Admitting a third option to the question of sex would depart from scientifically-grounded theory of human sexual dimorphism.

The mother of a disabled daughter was concerned that her daughter’s need for same-sex intimate care would be legally considered as bigotry. She thought her daughter’s dignity and safety more important than the feelings of a grown man. There were those, politicians included, who viewed a female’s refusal to have a man identifying as a woman deliver her “same-sex” intimate care as akin to racism.

Material reality

But the material reality of a man is not changed by how he perceives himself. Telling vulnerable women and girls to ignore their own discomfort to accommodate a man’s perception of himself is unjust and demeaning.

Others believed that attaining an independent Scotland was the only priority. Women’s sex-based protections were merely a side-issue, a distraction. “Wheesht for indy” was to be the strategy, and once an independent Scotland emerged, we might restore women’s rights. Or then again, we might not. It was intended to divide Britain, to demonstrate how different Scottish laws could be.

‘Telling vulnerable women and girls to ignore their own discomfort to accommodate a man’s perception of himself is unjust and demeaning…’

Journalist Mandy Rhodes comments, “it’s ironic given that identity is at the heart of all our politics that it was actual identity politics that destroyed Nicola. I do think it destroyed her; if this whole debate hadn’t happened, if those pictures of Isla Bryson hadn’t driven a coach and horses through the idea that there were no risks around self-ID, she could still be around.”

The editors note that Sturgeon was failing in her two major commitments – closing the attainment gap between children from the richest and the poorest households, and securing a second independence referendum – and may have been looking for an easy win. How wrong she was.

By early 2023, and in the wake of the Graham/Bryson crisis, Sturgeon’s stubborn adherence to self-ID weakened her so much that she had little social or political capital left to deal with other major issues: the police investigation into the SNP’s finances, her failing independence strategy and much more.

The book’s editors see this as a story of failure of devolved Scottish politics, as devolution approached its quarter-century. The democratic renewal promised by establishing the Scottish Parliament was largely absent, with a small but influential group of activists dominating the political process, from civil servants to the first minister, and across the parties.

Women’s rights were sacrificed in the name of “progress”. The SNP-led Parliament ignored public opinion and failed to properly scrutinise poorly conceived legislation. The campaign to resist self-ID exposed how distant Holyrood had become from its electors, even disdainful of those outside its bubble – the very charge laid against Westminster by those who had campaigned for devolution.