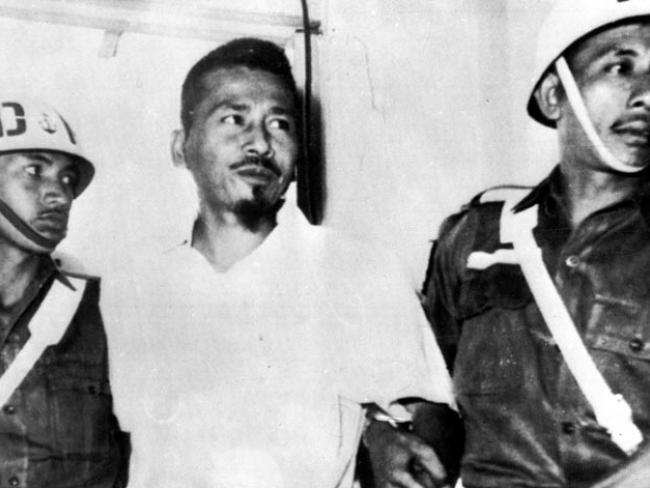

Djakarta Communist leader Njono going on trial in February 1966 in the aftermath of Suharto's seizure of power. He was executed in 1968. Photo Smith Actiive/Alamy Stock Photo

Sixty years ago a bloody coup wiped out the Indonesian communist party, and along with it all the trade unions and peasant associations…

In the 1960s, the US and British governments were in a panic about the spread of communism, and any countries attempting to wrest independence from the NATO-led world imperialist order. The Vietnam War was ongoing.

They feared the rise of a so-called Third World. Indonesian President Sukarno was a leader in setting up the Non-Aligned Movement, after a conference in Bandung in 1955 that he hosted.

Indonesia was a particular worry. It had freed itself from Dutch colonial rule in 1949. The communist party, the Partai Komunis Indonesia (PKI), was the strongest force for independence and the third largest in the world by number, behind the USSR and China.

Anglo–US collusion

In 1962, US president John Kennedy and the British prime minister Harold Macmillan agreed to “liquidate President Sukarno”, according to a CIA agent who summed up their off-record conversation. The two governments committed themselves to provoking a clash between the army and the PKI, presuming a defeat for the well-organised, but unarmed, political party.

Secret US national security documents explicitly endorsed the use of all feasible covert means to prevent Indonesia from falling under communist control. In 1960 the USA’s National Security Council (NSC) proposed that a premature PKI coup would justify the army’s destroying the PKI.

Britain became the largest seller of arms to Indonesia’s army – including bombs, ground-attack aircraft and riot-control vehicles.

From 1962 the US government sharply ramped up its aid to the army and also trained 2,100 Indonesian military personnel in the USA.

In February 1964, the British prime minister Alec Douglas-Home agreed a division of labour in Southeast Asia with US president Lyndon Johnson. The US government would support Britain’s role in Malaysia, and the British would support the US war on Vietnam.

From summer 1964, the US State Department developed an operational plan for political action in Indonesia. The NSC’s secret 303 Committee approved the proposed covert action programme, with immediate effect, on 4 March 1965.

‘The British government’s support for this murderous counter-revolution was part of long-standing British practice…’

The British government joined in the plotting. The Foreign Office approved the NSC idea of a premature PKI coup, predicting that the PKI might take many years to recover if they were soundly beaten.

A Dutch intelligence agent said that in September 1964 NATO intelligence agencies were organising a premature communist coup. This would be foredoomed to fail, providing a legitimate and welcome opportunity to the army to crush the communists and disempower Sukarno.

On 1 October 1965, the premature coup desired by the USA and Britain took place, the work of a small group of PKI persons who arrested and killed six generals in order to prevent a military coup, they said.

Immediately, army general Suharto then organised the real coup d’état; he later became president. The British government did all it could to help the army smash the PKI. The Royal Navy escorted a ship full of Indonesian troops down the Malacca Straits so that they could join in the killing.

On 5 October 1965, the British ambassador to Indonesia, Andrew Gilchrist, called for “early and carefully [planned] propaganda and psychological war activity to exacerbate internal strife” to help ensure “the destruction and putting to flight of the PKI by the Indonesian Army.”

Air Marshall John Grandy, head of Britain’s Far East Command, recommended using propaganda and psychological warfare to “try and ensure continuing civil war in Indonesia.”

In the name of destroying communism, the army destroyed all the people’s organisations, especially the trade unions and peasant associations.

Through manipulation of the media and covert propaganda outlets, Britain ensured that news coming into Indonesia supported the stories that the Indonesian army was spreading.

Gilchrist reported in April 1966 that its propaganda pressure on Indonesia had been effective in helping to break up the Sukarno regime. Grandy considered that Norman Reddaway, a Foreign Office official with a background in anti-communist propaganda, had made an outstanding contribution to the campaign.

Mass murder

The Indonesian army carried out a programme of extermination – the mass murder of an estimated 500,000 to 1 million innocent, unarmed civilians, maybe more. A US diplomat provided lists of Indonesian communists to Suharto’s forces when the mass killings began. The NATO powers assisted as much as they could: the killings advanced NATO’s global anti-communist crusade.

British policymakers celebrated the killings. On 18 March 1966, Gilchrist told the Foreign Office that Suharto’s seizure of power “must be one of the most sweeping, yet skilfully and constitutionally engineered purges of government in a world where violence and lawlessness in the change of governments has become all too familiar.”

Indonesia was forced back to exploitation by foreign, mainly US, capital, with the usual policies – privatisation, spending cuts, guarantees for foreign investors, wage cuts, rule by the IMF and the World Bank.

The operation to destroy the PKI – especially the use of deliberate provocation, psychological warfare tactics, and death squads – became the acknowledged model for many other covert anti-communist operations, especially those conducted by the USA in Central and Latin America from the 1960s onwards. US journalist Vincent Bevins called this “The Jakarta Method”, in a 2020 book of that name which goes into detail about the motivation and actions of the US.

The British government’s support for this murderous counter-revolution was part of long-standing British government practice. The Foreign Office generally preferred a strong military regime to a communist regime. Better fascism than socialism.