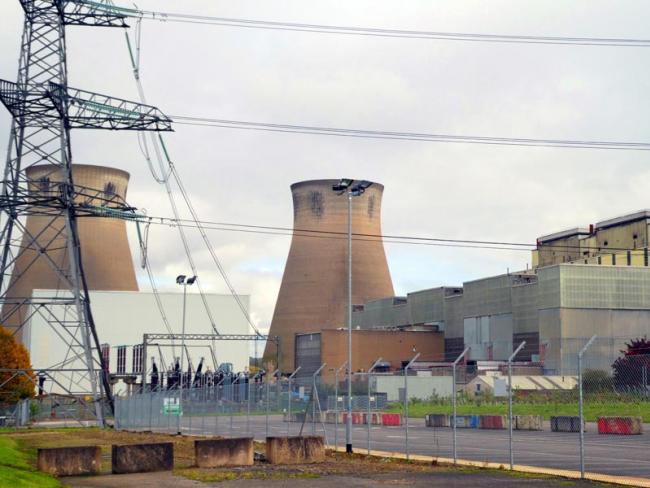

A shadow of its former self: Ferrybridge now produces a mere 68 MW of power, less than 5 per cent of its previous 2 GW capacity. Photo Workers.

Yes, it’s possible to produce energy without using nuclear power or fossil fuels. But at the moment the price tag for that will be a reversion to pre-industrial levels of production and consumption. No central heating, anyone?

The demolition of a further four of the cooling towers at Ferrybridge C power station in West Yorkshire, which took place on Sunday 13 October, was fêted by local media as a tourist attraction, with crocodile tears at the loss of a highly visible landmark on the M62.

With one tower already down in July, this was a vivid reminder of the parlous state of energy policy in this country, where certainty of supply is sacrificed on the altar of “greener” power. Sky News reported the event as a milestone, though in terms of energy policy, millstone would seem more appropriate.

The station is owned by SSE, itself a hybrid of the North of Scotland Hydro-Electric Board and the Southern Electricity Board, following privatisation in 1990/91. SSE, with a growing interest in renewable energy, deemed Ferrybridge C uneconomical, and closed it down in 2016.

Speculative

Three of the towers remain, on the off chance that a gas-fired station may be built on the site. In other words an admittedly old but still fully functioning unit which has provided us with reliable energy for 50 years has gone, and a speculative gas-fired station may or may not replace it.

Meanwhile, at the even larger neighbouring Drax station, the Government’s Planning Inspectorate ruled that the decision to replace coal fired units with state of the art gas turbines should be blocked because of their impact on climate change. This despite the newer turbines being cleaner and more efficient than the old ones.

Fortunately, on this occasion, the Secretary for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, Andrea Leadsom, overruled the Inspectorate on 7 October and gave the go-head for the gas turbines, noting that there would be substantial battery storage, and that the plant would be engineered to allow carbon capture equipment to be fitted.

Welcome as this development is, amid the shrill cries of Extinction Rebellion and others for pre-industrial levels of energy production and consumption, the government has yet to grasp the nettle that for the foreseeable future renewables will not be enough, and that a mix of fossil fuel and nuclear will be vital. Otherwise, there will be an increased risk of repeats of the blackout on 10 August, which brought chaos to airports, roads and railways, and left a million homes across the country in the dark.

This was the result of two power outages at the same time, one at the German-owned Little Barford gas-fired power plant, the other at the Danish-owned Hornsea offshore wind farm. These combined to produce a severe drop in the intensity of energy supply – too little to keep the network flowing smoothly. It also emerges that in the three months prior to the blackout there were three near misses, when grid frequency dropped to dangerously low levels.

Renewables

This is becoming more of a problem since we started to become increasingly reliant on renewable energy. It presents greater challenges to a National Grid which was designed to accommodate fossil fuel power plants. Of course there is a place for renewables as part of the mix in a modern energy policy, and huge strides have been taken in recent years, not least in offshore wind farms, but renewables on their own are not a silver bullet.

‘For the foreseeable future renewables will not be enough.’

As a chartered engineer with 39 years in the electricity supply industry put it in a letter to the Daily Telegraph this October, “…Renewable generation – solar, wind and tidal – is, by definition, non-synchronous and it is technically impossible to operate our electricity transmission system solely on non-synchronous generation. There is a real danger of system instability and consequential widespread blackouts once non-synchronous generation exceeds around thirty per cent of total generation at any one time. The National Grid report on the recent blackout referenced lack of inertia (in electricity terms, kinetic energy) in the system. This resulted from insufficient large synchronous generators (nuclear, coal, gas) being connected, said the engineer.

Politicians (Rebecca Long-Bailey, the shadow energy minister among the most strident) call for renewables to provide most of our energy mix by 2030, and at the same time wail about the blackout which their policy would make worse!

The holy grail of zero emissions, whether by 2050, or 2030 as some Greens and Labour zealots propose, is a sop to people’s genuine concerns about climate change and pollution. It adheres closely to the EU agenda, which dictates that it alone will determine a member state’s natural resources and how they are to be harnessed and deployed. Little wonder that Norway has resisted the lure of EU membership.

Fundamentalism

The debate in Britain about fossil fuels is bedevilled with sophistry and Old Testament levels of fundamentalist thinking. Coal was branded dirty, polluting and evil, and ruthlessly purged from our energy mix to the point where it can probably never return. True, coal was dirty, but we devised methods of cleaning it, such as carbon capture and scrubbing. We exported these to the world, but failed to deploy them at home.

Oil and gas, thought not to be so high on the scale of evil as coal, are also viewed with suspicion. (It would be instructive to learn how the executives at the Royal Shakespeare Company and the National Theatre, who have ended sponsorship from BP and Shell, travel to work and play. Bicycles and rowing boats perhaps!) And this pseudo-scientific approach has damaged the recognition that nuclear power is the most carbon free of synchronous providers in the energy mix.

If cutting edge engineering can continue to give us access to fossil fuels on the

bottom of the sea bed, and scientists can demonstrate how they can be extracted and used more cleanly, then we really

can’t afford to turn our noses up if we wish to continue to grow a modern, industrial economy.

The Brexit impasse has compelled millions of us to rethink our view of politicians and self-proclaimed experts. We could use some of that contempt in the minefield which discussion of energy policy has become.

The last word goes to the engineer quoted above: “…Given the need to reduce carbon dioxide emissions, the only option is to increase significant nuclear build rapidly. Both Labour and Conservative governments have been unwilling to commit themselves to this, which has led us to the problems we now face. It is unfortunate that politicians and environmental campaigners are ignorant of the technicalities of energy supply, or wish to ignore them. MPs may have the power to change the laws of the land, but not to change the laws of physics”.

• Related article: How Norway does it