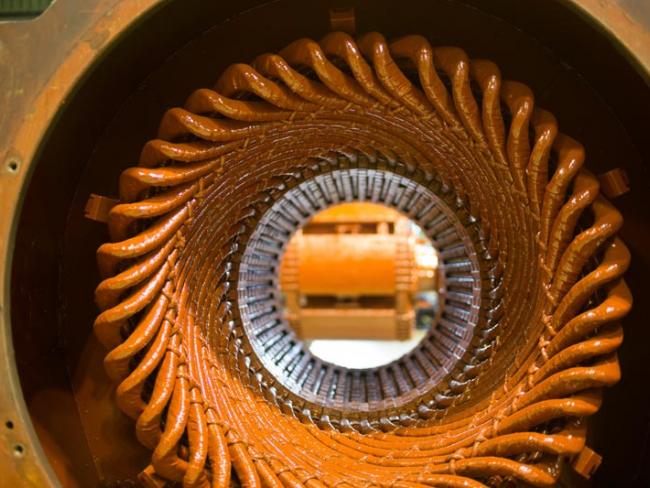

Copper is vital for electric motors and generators. Photo Kopytin Georgy/shutterstock.com.

With the transition from traditional sources of energy to all-electric, Britain’s security of supply is in question as never before. And with it, the issue of national self-reliance…

The background of war in Ukraine and the Middle East, and the simmering tension between China and the USA, with NATO stoking the fires, all make securing our energy vital.

Energy can’t be considered without acknowledging a string of metals and minerals critical to its production. Heading the list are the manufacture of high-grade steel and the extraction of oil and lithium.

Tempting as it is to get excited about newly topical elements like lithium and rare earths, we should not forget copper. It’s the one traditional material without which this electrical age cannot function at all. No copper, no green economy.

Copper is unequalled for its capacity to conduct heat and electricity, and its ability to be pulled and stretched. It is also resistant to corrosion and suitable for recycling.

In 2022 the government finally recognised the importance of critical materials with the announcement of a strategy entitled Resilience for the Future. But like most government announcements, it was long on fine words and short on concrete action.

Refresh?

Then in March 2023 came an update, a “Refresh”, intended apparently to firm up areas of action and make it clear precisely what the government would do. Yet, as the House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee noted in its report published on 15 December, it failed to do this.

“Government repeats that it will ‘encourage investment along the whole critical mineral value chain’ without addressing where within the value chain the UK should position itself,” said the committee.

In other words, there’s no clarity in government at all. That’s par for the course. Jeff Townsend, Director of the UK Critical Minerals Association, told the committee he’d first raised the question with the government in 2012, adding, “I’ve been banging my head against a brick wall ever since.”

And as Townsend’s Association noted in its response to the strategy, a number of minerals deemed critical in many other countries (including the USA) don’t figure on the UK list. That, astonishingly, includes copper.

Between 2020 and 2050 the proportion of energy derived from electricity is forecast to rise from 20 to 50 per cent. Electric vehicles will need three or four times as much copper as conventional vehicles – half going into the motors, half into the wires and battery.

At the core of the generator of the world’s most powerful steam turbine at nuclear station Hinkley Point C is coil upon coil of copper, turning motion into electrical current. It’s the same for all means of generating electricity.

Offshore wind turbines need ten times more copper – for electromagnets – than a conventional power station, to generate the same amount of electricity. Solar panels would need roughly seven times as much.

‘Decreasing our carbon footprint means increasing our copper footprint…’

In short, decreasing our carbon footprint means increasing our copper footprint. This is an inconvenient truth for the advocates of net zero – and for those who oppose all mining, anywhere.

Britain was once a copper producer, primarily in Cornwall. But it was Swansea which became the smelting centre – because of coal. Swansea had no copper, but showed it was possible to dominate production without having any metal in the ground.

Today China follows suit, smelting and refining half the world’s supply of copper. Britain is now entirely dependent on outside sources for its critical minerals, primarily China. That gives China enormous political leverage.

The world will need more copper to increase the supply of electricity, but there’s a problem. Mining operations all over the world are under threat because of environmental opposition.

Companies will not always meet the costs associated with green mining. And courts are agreeing to limit extraction of the very metal needed to wean the world off fossil fuels. “Just Stop Copper” would be tantamount to “Just Stop Electricity”.

Copper mining once took the tops off mountains, but mining is now mostly underground. It’s highly automated: the whole operation can be controlled remotely. But with so few at the pit face, how can future generations, with no hands-on experience, learn about materials and production?

Extraction of metals may yet pass from land to undersea-based mining. Since 1872, with the laying of the first transatlantic telegraph cable (which itself used a lot of copper), it has been known that a massive underwater mountain range exists in the mid-Atlantic.

Abundance

Scientific research deep in the ocean there has confirmed the existence of copper in abundance – an estimated 230 million tonnes, equal to more than ten years’ current output. There’s also iron, zinc, selenium and chalcopyrite (up to 20 per cent copper). Under the Pacific too, high-grade cobalt and nickel, manganese and copper have been found – metals critical to production of high-performance batteries.

These estimates are being revised after the most recent exploration of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge in the Sargasso Sea. Intended as a joint UK–Russia undertaking, it ended up as a UK-only mission in late February 2022, after the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Therein lies the challenge, and it is a question of control and cooperation. Who owns the seabed? And who has rights of exploration and ownership of its minerals?

Modern submersible technology (deep sea rigs) would allow Britain to take part in undersea mining. We would be up against stiff competition, because much of the seabed has already been claimed: China has four contracts, South Korea and Russia three each, Germany, France and Britain two each.

Almost unbelievably, Britain sold its two undersea copper mining claims to US defence company Lockheed Martin in 2013. But the story doesn’t end there. In March 2023, Lockheed sold the claims to a Norwegian company. Control has effectively passed from Britain to the global marketplace.

Of course, the sea bed might not be mined at all. The International Seabed Authority (ISA), the UN body charged with managing most of the ocean floor, has dawdled in drafting the necessary rules, giving time for environmental concerns to reach the courts. In 2022 Chile, already nervous about its copper mining on land, called for a moratorium on deep-sea mining and was joined by Fiji, France, and other nations.

As recently as 28 November 2023, Panama’s Supreme Court, overturning a law passed only the previous month, ruled that the Canadian mining company First Quantum’s contract to operate a lucrative copper mine in Panama was unconstitutional.

Economic consequences inevitably flow from closure of mines, not least for the cost of electrification as shortages push up prices. At the same time scientific curiosity in the little-known marine world is growing. Biologists and miners will need first to come to an agreement among themselves, then take their united professional opinion to the ISA and the public.

Markets

While the government continues to place its faith in the global markets, it has made no commitment to develop copper production in Britain itself. And there are sizeable potential reserves in Cornwall and Wales.

Work began in October at Cornish Metals’ South Crofty site to pump water out of the old mine as a prelude to developing future production. Another company, Cornwall Resources, is developing a project in Redmoor with considerable promise for copper.

Admittedly, it will take many years to build up a sizeable copper-producing industry in Britain, but that’s no reason for government not to play its part. Quite the opposite: it’s a pressing reason to start right now.

In the meantime, with copper and with other strategic materials, Britain is in the hands of global markets. And as experience has proved, that’s not a comfortable or safe place to be.