Part detective story, part hymn to the power of chemistry, this novel from Fiona Erskine also describes how an industrial powerhouse declined and fell…

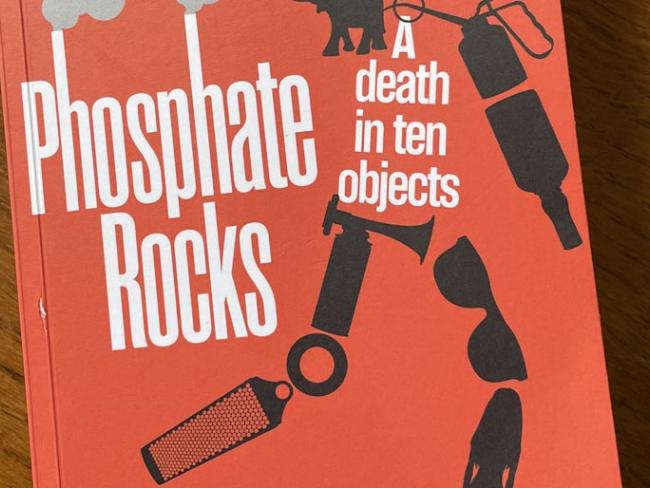

Phosphate Rocks: A death in ten objects, by Fiona Erskine, paperback, ISBN 978-1-913207-52-6, Sandstone Press 2021, £8.99 but widely available for less. Kindle and eBook editions available.

Around a dozen pages into Fiona Erskine’s Phosphate Rocks you realise this is no ordinary detective story. A whiff of sulphur detected by the laconic protagonist John Gibson, now retired from Scottish Agricultural Industries (SAI) in Leith, leads to a short, gripping discursion into the hellish sulphur mines of 19th-century Sicily.

From there the narrative leads to the creation of the Mafia as a strike-breaking army, and on to mass emigration after the mines were closed.

The theme of closure runs throughout the book – the end of Scotland’s fertiliser industry above all. SAI, with a history going back to the nineteenth century, used to employ 2,000 workers in Scotland, 340 of them at Leith, where this story is set.

In the second part of the twentieth century, SAI was run down by the parent company, ICI. The Leith factory, the last to go, shut in 1991 as ICI’s whole fertilizer division was sold to Norwegian conglomerate Norsk Hydro.

The story starts with the discovery of what clearly is (or rather was) a body encased in phosphate rock at the site of the SAI plant. By the body are the ten objects of the title: each has its own tale, which John Gibson unravels. What follows is in part a hymn to the glories of minerals and their role in production and agriculture. Sulphur, phosphate, potash, ammonia, guano, platinum and silver.

Occasionally you feel you’re getting a little too much information. But you need to bear with the author as Erskine worked at SAI for four years as a chemical engineer. Every incident – bar one – described in the book took place at some time during her stint there. John Gibson, too, is a real figure, still alive and a firm friend of Erskine’s.

The book progresses as a detective story: histories and tales are woven around each object. But gradually another theme emerges with increasing clarity: work, how workers combine to produce despite the greed and stupidity of the factory owners.

At this point, a very good book becomes something outstanding. By the end of it you have more than an inkling of how the decline of Britain’s manufacturing industry played out.

Skills

One of the key sections is about a group of “unskilled” workers known as greasers (one of whom is the only truly fictional character in the book, Becksy). The chapter about them starts with a forceful declaration: “They called them unskilled men. John always bristled at the lazy language. Some of the most highly skilled men he had ever worked with had been labelled ‘unskilled’. Management-speak for someone without paper qualifications.”

Erskine relates how a reorganisation from head office – snappily titled “The Way Ahead” – inspired by management consultants started with decentralising maintenance. The greasers, so-called unskilled and paid a pittance, were the first to go.

Yet the greasers did more than apply the right quantity of the right grade of grease at the right time, they listened to the machinery to decide what was needed, and told the mechanics if there was something off. “Now, no one was listening,” writes Erskine.

So a key gearbox seized up, and an entire granulation plant had to be taken offline, at a cost of £150,000 for repairs and £400,000 in lost production. Never short of a minerals comparison, Erskine takes the price of gold at the time (1988) – £250 an ounce – and translates £550,000 into 70 kilograms of gold. Becksy, she concludes, “had literally been worth his weight in gold”.

‘The author peppers her story with anecdotes that both entertain and shine a light on society…’

A similar debacle is described with the commissioning of a new plant to make ammonium nitrate, a key fertiliser sold by SAI under the brand name Nitram. The task was assigned to the hapless Keith. When someone is introduced as “a contract mechanical engineer who could quote British Standards verbatim but avoided eye contact”, you know disaster is just around the corner.

The extent of the disaster is mind-boggling, and Erskine describes it in forensic detail, including erroneous (and eventually, very expensive) assumptions about the specifications for the new machinery. Other factors contributed to the debacle too: flowing through them all like a sparkling seam of fool’s gold is the lack of respect for the knowledge of workers.

Solved

In the end the detective puzzle is solved, and the identity of the body encased in phosphate revealed. But a number of things raise this book from being merely a good crime story. Erskine writes well, with an economy of style sprinkled at times with searing irony. And she peppers her story with anecdotes that both entertain and shine a light on society.

For example, she writes, as she must, about Fritz Haber’s invention with Carl Bosch of a process to make ammonia from nitrogen and hydrogen. But she also writes about his wife, Clara Immerwahr, the first woman to get a doctorate in chemistry in Germany.

Haber enthusiastically developed chemical weapons in the First World War. Immerwahr was violently opposed. In 1915, they argued as Haber was about to go to the eastern front to supervise a chlorine attack. Erskine continues: “She took his pistol and shot herself. He left anyway; it took her several days to die.” That’s all you need to know about Haber.