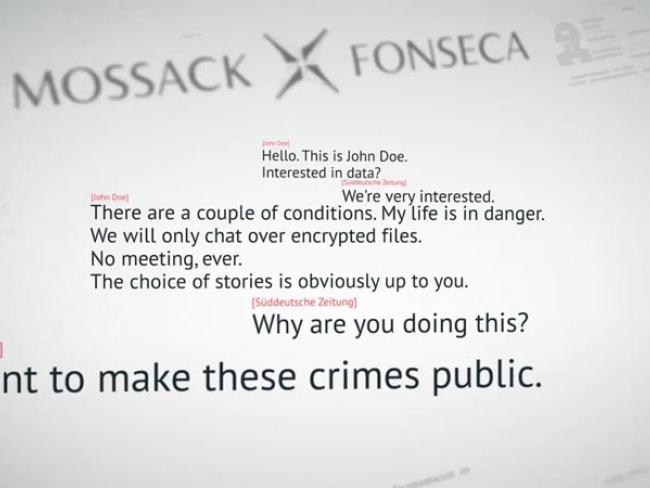

The (translated) conversation between the Süddeutsche Zeitung and “John Doe”

The Panama Papers: breaking the story of how the rich and powerful hide their money, by Frederik Obermaier and Bastian Obermayer, paperback, 366 pages, ISBN 978-1-78607-047-0, Oneworld, 2016, £12.99 or less, Kindle and e-book editions available.

Frederik Obermaier and Bastian Obermayer work for the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung. In early 2015 Obermayer received a message, “Hello. This is John Doe. Interested in data?” This book is the story of what happened next.

The anonymous source had the entire internal database of a major Panamanian law firm, Mossack Fonseca, one of several specialising in setting up offshore shell companies.

More than 500 banks and over 200,000 offshore companies across the world have used Mossack Fonseca. There were links to 35 heads of state. Now 400 journalists from 80 countries are working on it, many as part of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists.

In February 2015, public prosecutors and tax investigators arrived at Commerzbank in Frankfurt, Germany’s second largest bank. The bank had apparently been routinely and systematically helping German clients to evade taxes; Mossack Fonseca was one of its accomplices.

Commerzbank’s Luxembourg subsidiary set up companies based outside the EU for its clients to avoid the EU Savings Tax Directive. That orders all Luxembourg and (through a related agreement) Swiss banks to deduct a flat rate of up to 35 per cent tax on all gains in unregistered accounts belonging to EU citizens.

Tax evasion

The authors conclude that Commerzbank and numerous other German banks “...were evidently actively and systematically involved in helping clients evade tax.” EU member states lose a thousand billion euros a year through this kind of tax evasion. Commerzbank agreed to pay 17 million euros in fines for their dealings with Mossack Fonseca, so that legal proceedings against the banks are closed.

The authors comment, “While billions were spent bailing out banks, and nearly all those responsible got away without being investigated, let alone charged, the victims, the people conned into taking out enormous loans, were abandoned often without a job, a house or any prospect of ever being able to live debt-free again.” Merkel’s government gave Commerzbank 18 billion euros during the 2008-09 crisis.

Governments have failed to deal with these scoundrel states. International institutions have failed. Parliaments, courts, the legal profession, the media have all failed. When whistleblowers are necessary, the whole system has failed.

For example, a Luxembourg court found Antoine Deltour, a former employee of PricewaterhouseCoopers, guilty of theft because he brought to light hundreds of “sweetheart” tax deals between Luxembourg and multinational companies.

The current president of the European Commission Jean-Claude Juncker was previously the prime minister of Luxembourg. He of course defends Luxembourg’s actions as legal, but even the Commission as a whole took the view that Luxembourg had granted illegal tax benefits to multinational companies.

The authors also point out that Britain’s island territories are “unquestionably the cornerstone of international corruption worldwide”. As a tax expert told the House of Commons Treasury Committee, “it would have been impossible for the current credit crunch to have happened if offshore had not existed.”