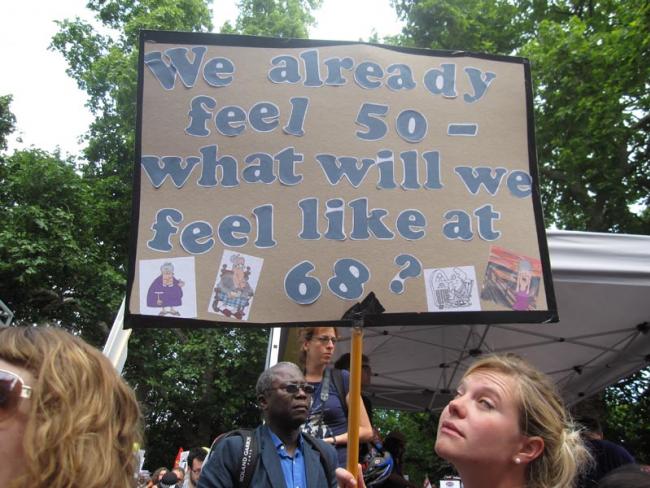

What the economy needs is earlier pensions, rather than later and later retirement – due to be 68 for those born after 1978. Photo Workers

The referendum campaign blunted one EU attack on pensions. Now the real pensions fight must begin…

Even before the vote to Leave, the Brexit campaign had already pulled off one stunning result: it had – for the time being at least – halted the attack on workplace pensions. Nevertheless it has not stopped those still in the Remain camp from trying to make out that the European Union protects UK workers’ pensions. Quite frankly, that idea is risible.

The fact is that since 1993 the EU has been ratcheting up its control over British pensions. Its latest attempt would have seen off the last of the final salary company schemes in existence (see Box below).

In the wake of the referendum result, the TUC has called for action to protect pensions. Astonishingly, it is now saying, “The Pensions Regulator should allow maximum flexibility in scheme funding to ensure that short-term volatility doesn’t lead to a fresh round of pension fund closures.” Quite right, it should. But it has been precisely the EU that has put the screws on funding flexibility!

British workers have never had a “generous” state old age pension. But after 1945 the level of State Pension was supplemented for many workers by access through their workplace to a final salary occupational pension. It was the trade unions, particularly in the Civil Service, that led the way, with action resulting in the introduction of these schemes in the 1950s.

Over the decades, the law changed to allow pension scheme membership to become automatic when a worker joined a company with a final salary scheme. Workers usually contributed up to 5 per cent of their pay, with the employer contributing between 12 and 18 per cent.

Undermining

The government’s first attempt to undermine final salary pensions came in 1987. The chosen tool was the so-called “personal pension”, which workers could take with them as they moved between employers. To encourage the shift, the government also changed the law so that workers starting a new job with an employer that offered a final salary pension were no longer enrolled automatically in the plan.

“The EU would have seen off the last of the final salary company schemes.”

Many workers took the government’s prompt. They thought they could do better by not paying into a collective final salary arrangement and instead take out a personal pension. They were wrong, and it marked the start of the onslaught on collective pension provision.

From the early 1990s the pension attack was further developed and became orchestrated through the EU. This began with the legal case of Barber vs Guardian Royal Exchange (GRE). As an employee of GRE, Mr Barber had gone to the European Court of Justice on the grounds that his final salary pension was sex discriminatory.

The European Court duly agreed that he had been discriminated against and that all UK final salary pensions should be treated as equal pay with effect from May 1993 onwards.

The decision was a godsend to all those who wanted to attack UK pensions. Firstly it meant that all British final salary schemes would in future be subject to EU directives. Secondly the judgement, while masquerading as equality, provided the opportunity to raise women’s normal retirement age for an occupational pension from 60 to 65, the same age as men.

Maxwell

The next step in the attack came through the 1995 Pensions Act. Using the Maxwell affair, where Mirror Group pension investments had been embezzled by the company’s owner, Robert Maxwell, the Act took the opportunity to give full vent to market forces to compare the assets of a pension scheme against its liabilities.

Scheme funding had always been assessed over the long term. But making schemes subject to destructive short-term market fluctuations produced paper deficits that could then be used as a pretext to close final salary schemes.

To further increase the deficits of final salary schemes, the 1995 Pensions Act also declared that a minimum rate of increase (inflation proofing) should apply to all final salary pensions from 1997 onwards. Over time, along with ongoing market forces, the “gift” of inflation protection would serve to further balloon scheme deficits by another 20 per cent or more.

The 1995 Act also enabled the equalisation (upwards) of retirement ages to be extended from company schemes to the State Pension. But for technical convenience, rather than go through the European Court of Justice, the 1995 Act utilised the European Court of Human Rights to declare that UK State Pension benefits should only be paid from age 65 onwards – massively reducing benefits for millions of women.

Having put the legalities in place, the next step was for Labour’s Chancellor Brown to co-ordinate his 1997 tax raid on final salary investments to coincide with the EU Action Plan which at national level eventually ushered in Britain’s Financial Services Authority (FSA – now the FCA, the Financial Conduct Authority) as a financial products regulator in 2000.

Brown’s raid – still an annual tax grab from schemes – has since provided the government with £10 billion each year in revenue and is another key contributor to the poor state of occupational pensions today.

Subordinated

From 2005 onwards the FSA was to be accompanied by the Pensions Regulator, another EU conduit. In turn both the FSA and the Pensions Regulator were to be formally subordinated to the European Insurance and Occupational Pension Authority (EIOPA) in 2011.

Germany does not have any final salary pension schemes, but even so EIOPA was to be based there. It is from Frankfurt that it now issues its UK pension directives for implementation by either the FCA or the Pensions Regulator.

From a British perspective the main task EIOPA set for itself was to think up more destructive ways of inflating deficits. Hence the so-called “MiFID” initiative (see Box), which also tied in with the government’s attack in 2010/2011 on final salary schemes in the public sector.

After Brexit, what next for pensions? Free of the EU, workers should be thinking of forcing a huge increase in State Pension and making it payable from age 60 onwards. Experience has shown that any other form of pension provision sooner or later ends up becoming a free market basket case.

Decent pensions at 60 would also free up work opportunities for our younger workers by allowing older workers who currently cannot afford to retire to do so. It is self-evident that if older workers stay longer in the labour force this must reduce the opportunities for young British workers in the labour market. Successive pensions policies have amounted to an attack on both younger and older workers alike: this must now be reversed as part of Brexit.

• Related article: The EU's pensions vendetta