February 2018: UCU members picketing at the University of Bristol during their successful pensions fight. Photo Chris Bertram.

Despite progress in the universities pensions fight, the employers still do not accept – and many staff still fail to understand – that there is no pensions deficit at all. It’s actually a destructive fabrication imposed by EU diktat…

Members of the University and College Union (UCU) have just finished balloting on industrial action over casualisation, pay inequality and workload in higher education. In a message to members, the union called for the same high level of participation seen in the fight for pensions earlier this year – but members cannot take their eye off the pensions issue either. In fact, they are in danger of losing any pay increase they win to the costs created elsewhere by regulatory trickery on the pensions front.

As part of its resolve to keep open the biggest pension scheme in academia – the Universities Superannuation Scheme (USS) – the union persuaded the employers to set up a Joint Expert Panel (JEP) to review, independently, the valuation of the scheme.

That panel has now reported, and the UCU has welcomed the report, above all because thanks to their strikes, members now no longer face the immediate threat of scheme closure and the assumed pensions deficit is much lower than stated a year ago.

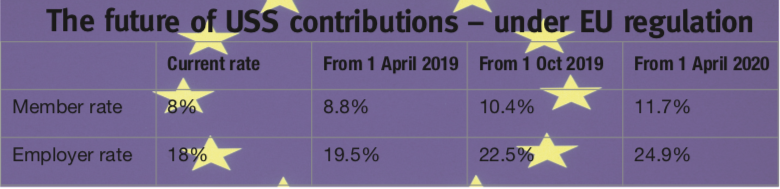

Hidden in the panel’s report is the suggestion that contribution rates will still have to rise – to more than 29 per cent. That is bad enough. Even worse, the JEP proposal runs counter to current regulatory requirements which are designed to produce a deficit and which, as at July 2018, imposed an end-loaded contribution structure that could well see contributions soar (see Table).

So UCU members still have a fight on their hands. Whether or not the JEP recommendation is considered acceptable the impact of the regulatory framework on contributions will cost them dear, and not only in take home pay for members. It could even prompt some university closures or the break-up of the current college structures.

And yet there’s no reason at all for increases in contributions, nor for cuts in benefits. In fact, based on interest rate history, the scheme can remain open to new joiners indefinitely.

As a means of long-term planning, the current financial methodology applied to British final salary-linked pensions is based on fleeting interest rate movements and should be junked. And this methodology is overseen and enforced by the EU.

Take an evidence-based analysis of the pension landscape, and what emerges is a subtly led EU assault on British workers’ occupational pensions going back many years. Only by using evidence as a basis will an understanding develop about how our pensions system has been decimated and how the attack can be repelled.

The EU first dug its claws into British pensions in 1992 through the European Court of Justice decision in Barber vs Guardian Royal Exchange. This case determined that occupational pension schemes were sex discriminatory if they had different retirement ages for women and men. Note that “equality” was achieved by raising women’s retirement age to that of men!

To add insult to injury, the retirement age for the state pension was put back in stages from age 60 for women and 65 for men to 68 for both. Yet more “equality” – this time administered initially through the European Court of Human Rights.

The next EU step was to change the way occupational pensions were valued. This took a little time to set up but was eventually smuggled in off the back of the EU’s Financial Services Action Plan of 1999 as implemented in 2000.

Deliberate

The change meant occupational final salary pension schemes would have their valuations conditional on short-term market fluctuations – because managers were essentially forced to take account of whatever rates were in effect when the scheme was (periodically) valued. Despite the current bleating about “unforeseen outcomes” the desired EU regulatory objective was to throw up large theoretical scheme deficits against a backdrop of falling interest rates.

The change in 2000 was introduced under the pretext of protecting British workers’ pensions – making them safer by forcing unnecessarily high future contribution rates to be paid into schemes. But those who design pensions regulation are not stupid. The real aim since 2000 has been to give the appearance that ongoing final salary pension guarantees are unaffordable.

The evidence that the aim was to prompt pension closure is there for all to see. Hundreds of schemes have shut, and the USS scheme – Britain’s largest in terms of assets – was one of the final targets.

The EU grip tightened in January 2011 when the European Commission created the EIOPA as a new Europe-wide supervisory authority. At that point, the EIOPA “empowered” Britain’s Pensions Regulator with “state of the art” supervision rules. In other words, the Regulator would continue to take its orders from the EU but within the more formal EIOPA framework. Ever closer union.

‘In plain language, our pensions policy is made at EU level, and Britain’s domestic regulator is simply an enforcement agency.’

In plain language, our pensions policy is made at EU level, and Britain’s domestic regulator is simply an enforcement agency. Once the new valuation regime had been installed in 2000, all that was needed was for market forces to do the rest. In this respect the dramatic fall in interest rates since 2000 has played a key role. Quantitative easing, providing cheap money to banks and forcing interest rates down, has been crucial to this ploy (see page 11).

Simply put, the lower the projected rate of interest, the more money is assumed to be needed now to hit a particular pension funding target at a future date. And all of this is based on guesswork at a moment in time.

Historical trends suggest it is likely that the interest rate cycle will revert to a higher pattern of rates than at present, especially as the costly policy of quantitative easing is progressively ditched. The timing of this unwinding is unknown, but the evidence is that when interest rates reverse it happens slowly at first and then suddenly. Those who study financial markets will be aware that the slow part of the interest rate reversion is currently in play.

UK rates have been at their lowest since records began around 1750. But the EU takes no account of longer term rate history. Instead, by using current super-low rates, it has given the opportunity for scheme managers and the Pensions Regulator to say there is too little money set aside in our final salary funds to pay pensions in the future.

Guesswork

But that’s little more than opportunistic – and politically inspired – guesswork at a time of record low rates. A wiser approach would be to look at interest rates over the past 200 years or more. During this period UK long-term rates tended to oscillate between 6 per cent and 2 per cent until relatively recently. In the 1970s they moved well above their historic band, only moving below 10 per cent after the European Exchange Rate Mechanism debacle of 1992.

Further, when you compare these past figures with present-day projected rates of around 1.7 per cent per annum for the next 30 years – the rates pension schemes are guided to – the historic disparity is obvious. This is reflected in more measured opinion in financial circles, where the view is that rates will shift towards between 3 and 4 per cent over the medium term, allowing other assumptions to improve.

Disappearing deficits

This matters. Using the long-term averages based on financial history, current pension deficits are likely to disappear over time like the snow in spring. Even now rates are starting to unwind and pension deficits are beginning to fall, though the improvements are still unlikely to be linear in the short term.

Academics and financial commentators who like an evidence-based approach would enjoy reading the History of Interest Rates (Homer and Sylla, published by Wiley and updated in 2005; the first edition appeared in 1963). This and subsequent studies come to similar conclusions on the way interest rates revert to their historic average over time.

Even a short-term look shows how the EU’s destructive set of interest rate assumptions work in practice. For example, what prompted the UCU’s fight to keep their USS Pension Scheme open was the EU-inspired result of the USS actuarial review as at April 2017, showing a theoretical deficit of around £13 billion. By November 2017 the “deficit” was assessed at £7.5 billion. It now sounds as if it is around £4 billion and falling.

These figures over an 18-month period clearly show the type of deficit lottery that the EU’s pensions methodology produces via its regulatory arm, EIOPA, whose diktat is delivered locally through its British franchise, the Pensions Regulator, based in Brighton.

Bill Galvin, who heads up the day-to-day running of the USS scheme, is a former chief executive of the Pensions Regulator. So he will be fully aware of the EU set-up and how it has been used against our British occupational pensions. But given the destruction he has been party to, it is unlikely he will want to share his EU insight with UCU members.

The good news is that with the brilliant referendum result in 2016 Britain will become an independent country outside the EU borders – and so we can now bin EIOPA and its supine local baggage.

In short, the UCU’s fight to retain the university workers’ pension scheme is a just cause. The history of interest rates is on their side. They need waste no further time poring over the EU’s financially illiterate pensions drivel. It is entirely politically motivated and anti-worker to its core.