6 August 2019

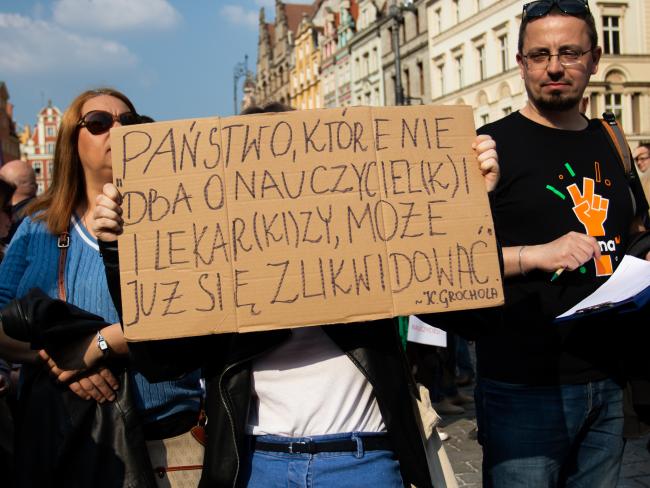

Striking teachers Wroclaw, Poland 7 April 2019 after pay talks with the government failed. The placard says ‘States that do not care about teachers and doctors are doomed to death’. Photo Lidia Muhamadeeva/Shutterstock.com

The Polish government is hoping to lure graduates back to work in Poland. More than half a million have left the country over the past 20 years. This is one part of a wider problem affecting many countries.

On1 August the Polish government abolished income tax for more than two million young people in an attempt to reverse what it called its “brain drain”. Poles under the age of 26 earning up to 85,500 zlotys (£18,200) will be exempt from the 18 per cent basic rate of tax.

Shortage

The government explained that Poland has an acute shortage of skilled labour especially scientists, doctors and IT specialists. It’s not just graduates that are a problem, many other young skilled workers are among around 1.7 million Poles who have sought work elsewhere. Over 750,000 came to Britain.

Maybe it is time for those British trade unionists who say that “all migration is good” and “our health service needs EU staff” to reflect on the impact at home and in many countries abroad. The CPBML has long documented the negative impact of the EU’s free movement of labour on skills training here in Britain and the grave impact on other EU countries, for example in Romania.

Low pay

However the Polish plan is a strange one and may not achieve its aims. It seems to institutionalise low pay by Polish employers. Introducing the tax break, Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki told their parliament: “We have to draw the young people back. …Employers were not ready to raise salaries for their young workers, so we will do it through scrapping their income tax”.

‘There is no substitute for fighting for pay and working conditions.’

But young Polish workers will find a big cut in their wage packet on reaching their 27th birthday as they outgrow the tax cut! Although Brexit could bring some benefits to Poland, their young people may discover, just like in Britain, that there is no substitute for fighting for a pay rise and improvements in working conditions and training.

Those leaving Poland are predominately young. The country’s median age has risen from 36 years in 2000 to 41 years now. But at the same time Poland has seen a rapid increase in immigration.

Poland granted the largest number of first residence permits among EU member states – 680,000 in 2017. Germany was next with 535,000 – against a population of 83 million compared to Poland’s 32 million. Britain was third highest with 517,000, double that of the fourth highest country, France.

No protection

Many migrants to Poland are from Ukraine since 2014 and the civil unrest surrounding the deposal of President Viktor Yanukovych. But Ukrainians in Poland frequently work in low paid, low skilled jobs, even if well qualified – the universal fate of migrants. Unlike Polish workers in other EU countries they have few legal protections.

The predictable result is a skill shortage in Ukraine too and damage to that country’s economy. By contrast in Ireland, a country historically blighted by emigration, the Department of Finance has complained that not enough migrants are arriving from the EU so wages are going up!