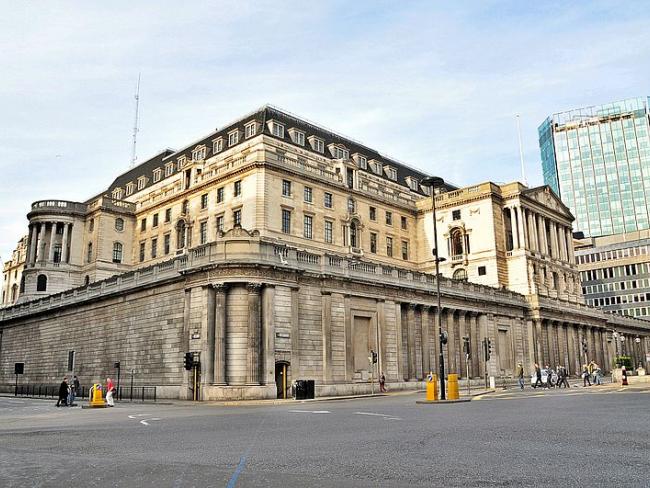

In the wake of the Chancellor’s Autumn Statement, Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of England, identified last week that real wages in Britain have fallen for the first time in 150 years. That takes us back to 1866.

Carney further identified that the main cause of dissatisfaction with capitalism, globally, is the failure of wages to rise against profits.

Two days later, over 30 food, drink, retail, manufacturing and export companies issued a statement that food prices will rise if we cannot rely on cheap labour from the European Union. There’s no danger to their profits, but the companies say they will pass on any additional costs to the consumer.

It’s a repeat of scaremongering and threats from multinationals that tried to intimidate supermarket chains in October, notably over the price of marmite.

Mass migration

In the same vein, the CBI – speaking for employers generally – is calling for further mass migration of cheap EU labour to areas which it defines as having low unemployment. In other words, bring in cheap labour to undermine established wage rates by utilising this reserve army of the unemployed.

The year 1866 was two years before the founding of the Trades Union Congress. But 1886 or 2016 the issues remain the same: wages versus profit and the pendulum balancing act. If workers are well organised the pendulum swings into the employers’ profit, if they are not the employer pendulum cuts into wages.

Cheap migrant labour undermines wage rates. Workers become accustomed to reduced wages, which leads to reduced standards of living. Hence the real importance of the Governor’s statement: long hours, low wages, unskilled flexible casualised workers at the beck and call of employers are driving living standards down.

Fighting for the rate for the job, controlling that competition which would undermine the rate, controlling the flexibility of hours and the dilution of skill are simple organising principles with which workers can respond to the Bank of England, the employer associations and their cartels.