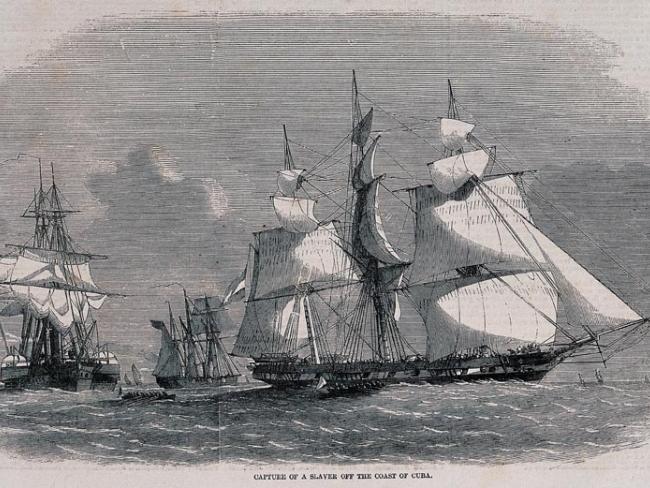

The capture of the slave ship Emilia off the north coast of Cuba by the Royal Navy ships Styx and Jasper. Wood engraving, 1858. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark

Only the ruling class benefited from slavery. During the long struggle to end it over 1.5 million of Britain’s 12 million people signed petitions against it…

Between 1660 and 1807, British-owned ships carried 3.5 million Africans across the Atlantic, more than any other country. British property owners were the world’s chief slavers, owning the slave ships, the slaves and the plantations. British workers did not control their own labour power, never mind own other people. Black chattel slavery and white wage slavery were parts of the same system.

Only the seriously wealthy could afford to engage in the lucrative practice of slave trading. Raising capital for the voyages stimulated the growth of the banking industry, and slave trading merchants established many of Britain’s first banks.

Rotten roots

Insurance and banking firms financed plantations and speculated on slave trade voyages. Bankers in particular gained from the trade: banking was almost wholly financed on the profits from the slave trade – the rotten roots of today’s finance capital.

The historian Padraic Scanlan wrote, “The profits of slavery pushed European empires into war while also intensifying inter-imperial and inter-colonial trade and exchange. … Slavery made the Caribbean profitable; profits provoked wars, wars ended in conquest; conquest led to new plantations and more slavery.”

Slavery helped to ruin West Africa. “The combination of failing manufacturing industries, depopulation, more frequent war and massive inflation crippled many West African economies. The economic crisis caused by the slave trade made slave trading central to many economies.”

In his famous book Capitalism and Slavery Eric Williams, later the first prime minster of Trinidad and Tobago, argued that the profits from the slave trade “provided one of the main streams of accumulation of capital in England which financed the Industrial Revolution”.

Slavery wreaked havoc across the world. But Williams was wrong. The profits from the slave trade – even if they had all gone towards industrialisation – were only a tiny contribution to capital formation. And much of those profits added to the private wealth of individuals who generally chose conspicuous consumption like building and furnishing country houses rather than investing in the industrialisation of Britain.

Popular

The struggle to abolish slavery in the British Empire was a hugely popular movement, but long and bitter. Between 1787 and 1792, 1.5 million Britons, out of a 12 million population, signed petitions against the slave trade.

But Parliament had a powerful pro-slavery lobby supported by prominent politicians such as Robert Peel and George Canning who both later served as prime minister. Between 1793 and 1804, abolitionism made little progress because the ruling class’s war against revolutionary France pushed aside all reform causes.

But by 1807 Napoleon’s blockade on British shipping helped to persuade politicians that it would be patriotic to oppose France by cutting off its supply of slaves. Abolition of the trade could be sold as part of the war effort!

‘Profits from the slave trade were only a tiny contribution to capital formation…’

An Act of Parliament to abolish the British slave trade was passed in 1807, but it did not end the practice of slavery. The pro-slavery lobby in Parliament remained strong. Only after the Reform Act of 1832, when 16 of their 35 MPs lost their seats, did the lobby lose its influence.

The 1831-32 slave rebellion in Jamaica helped to convince a wavering Parliament to pass the 1833 Slavery Abolition Act. The government compensated not the slaves but the slave-owners. And who paid? Nine future generations of British taxpayers and nine generations of the descendants of the enslaved within the empire, also taxpayers to the British Exchequer. It was finally paid off in 2015.

The government relied on banks to supply the money for compensating the slave-owners. In 1835 the Rothschilds bank bought £15 million in British government bonds which earned hundreds of millions in interest for 180 years, financed by British taxpayers. Lloyds Bank, Barclays Bank, the Royal Bank of Scotland, Baring Brothers, and at least 30 others all received slave-owner compensation.

British slave-owners directed their reparation money into new colonial pursuits around the world. They invested in slave regimes in the American South, Brazil and Cuba, in railway stocks in South America and the USA, in shipping lines across the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, and in Caribbean sugar production.

Others invested in plantations across Africa and Asia. Very little went into financing Britain’s Industrial Revolution.

Demands

The 1814-15 Congress of Vienna divided up power in Europe after Napoleon’s defeat. Anti-slavery campaigners conducted unprecedented waves of petitions – collecting well over a million signatures – demanding that the government supported the universal end of slave trading at the Congress.

The Royal Navy came out of the Congress with the power to police international waters, enabling it to play a key role in ending the wicked trade.

A permanent anti-slavery patrol operated on the West African coast from 1819 to 1859, trying to patrol 3,000 miles of Africa’s coastline. The Navy captured over 500 slave ships between 1819 and 1849, freeing at least 104,034 slaves between 1807 and 1839.

This must be set against the estimated 1,908,600 slaves taken from Africa between 1811 and 1839. The naval campaign was never going to stop the trade as long as open markets existed in the Americas.

The courage and sacrifice of the Royal Navy’s cruisers achieved the initial aim of destroying the British slave trade, ended slaving by the Netherlands, made the slave trade much more difficult and expensive for those engaged in it, and encouraged the abolition movements in the slaving nations.

But the end of slavery did not mean the end of forced labour or colonial rule. Caribbean former slaves were forced to work with little or no compensation for up to fourteen years as “apprentices” before they could finally gain freedom.