Silvertown: The Lost Story of a Strike That Shook London and Helped Launch the Modern Labour Movement, by John Tully, hardback, 288 pages, 2014 ISBN 978-1907103995, Lawrence & Wishart, 2014, £17.99.

The historian and novelist John Tully tells the story of a forgotten strike of 1889. The Silvertown strikers were employed by Samuel Winkworth Silver's rubber and electrical factory after which that area of London is named. This book is worth reading and digesting for its insights into how our class developed into an organised labour movement.

Tully brings the struggle of those workers back to life. His book takes you on a journey of understanding about the emergence of “new unionism” and the organising of the masses of unskilled workers in the late Victorian era. We can take inspiration from that time and apply it for today's workers who continue to struggle for better terms and conditions.

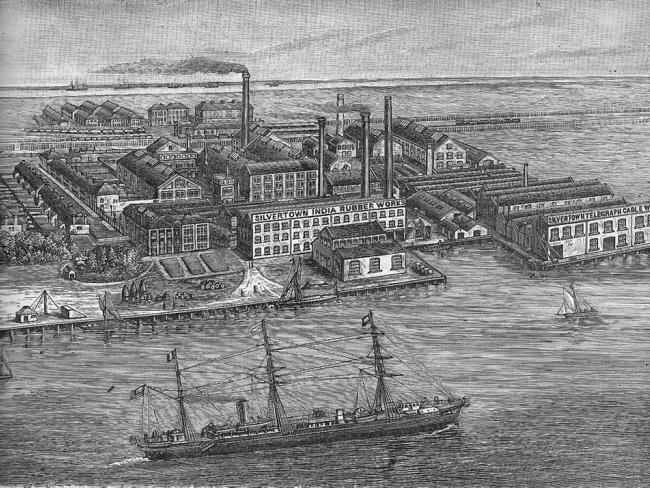

Silvertown was then at the heart of English heavy industry, lying between the Victoria and Albert Docks, then the largest in the world, and the River Thames. Silver’s factory was busy supplying the rapidly growing network of telegraph cables around the world. But the firm’s workers saw little gain, and a high proportion of them were casually employed.

New unionism

At the time traditional craft unions were the dominant working class organisation. They secured their membership by taking only men with a skill (craft). Craft unions were not interested in recruiting men or women who they believed were unskilled. These men and women worked in the industrialised factories of mass production. Their employment was often casual and uncertain and even in the relative boom time of 1889, poorly paid.

The workers having been ignored by traditional craft unions decided to engage with early socialists who led the new unionism then emerging, particularly in London’s docklands. New unionism recognised the need to recruit unskilled and semi-skilled labour. This new type of approach to organising workers saw a huge increase in the number of union members.

The Silvertown strike started in September 1889. It was well organised with support from leaders like Ben Tillett, Tom Mann, Will Thorne and Eleanor Marx. They had taken a leading role in the successful Bryant and May matchgirls strike a year earlier. Gas workers, newly organised at nearby Beckton had just carried out a successful strike for a shorter working day. The London dockers’ strike began a few weeks earlier and was soon to result in a famous victory.

‘The strike sent a message to the owners of industry about what can happen when workers are organised.’

Unskilled workers at Silver’s factory were not in a union at the start, but petitioned for a wage rise. It was refused; some of the unskilled and semi-skilled workers struck work. Support grew quickly, including from some of the skilled, organised workers. The strike paralysed Silvertown for three months. It sent a clear message to the owners of industry, what can happen when workers are organised, take inspiration from others and defend their right to better pay and conditions.

Employers were scared by the rise in militancy and determined to face down this latest challenge to their rule. They alleged that their “loyal” workers were intimidated by outsiders. Tully shows that was untrue; the workers sought help and then developed their own leadership in the course of the strike. Intimidation did happen – by the employers and their class. The force of the state was used, police and judges supporting the employer, who used tactics that many workers will recognise from miners’ and printworkers’ strikes of the 1980s.

The union sought relief funds for workers who were on strike. They raised general public awareness of issues affecting workers by leading peaceful demonstrations and meetings across the city. But they did not attract the same sympathy and financial backing that had helped the dockers at a critical time in their dispute.

Outcome

The employer offered no concessions or meaningful negotiation. It decided to face out the strikers, sensing that starvation and disagreements with some of the skilled workers not on strike would end the dispute in their favour. So it turned out; and despite the determination and courage of the Silvertown strikers they were unable to prevail.

This was no vainglorious token strike. The Silvertown workers started from their need for a decent wage but came up against the opposing class rocked by new unionism and determined to gain the upper hand again. And despite the spread of new unionism around Britain, the ruling class made other gains in the wake of Silvertown.

The lesson for workers was that the mercurial gains of the previous two years did not signal the end of exploitation. They had taken on again fighting for wages after years of humble petitioning. They fought for and won concessions from owners of industry. Leaders emerged from our class, influenced by and influencing socialist thinking.

The Silvertown strike and new unionism of that era were to launch a more radical modern labour movement, focused on workers being part of larger trade union struggle. This book about a different era helps us to understand our choices and struggles today as well as throwing light on the emergence of the TUC and Labour Party only a few years later.