4 April 2020

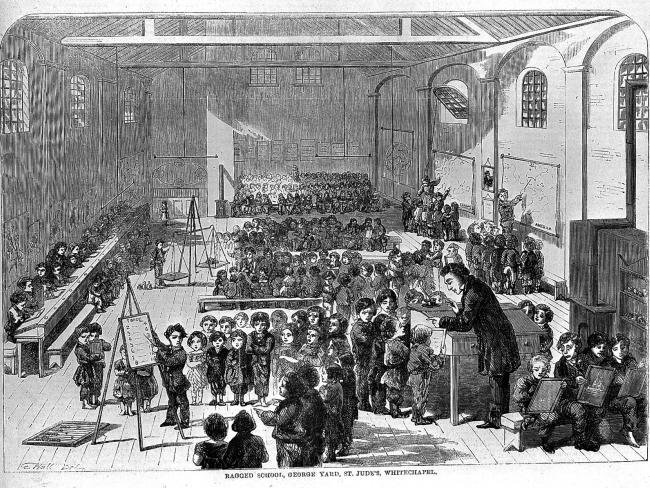

Ragged School, Whitechapel, London. These schools provided free education for destitute children before the 1870 Act; they showed the demand for universal education. Image Welcome Library, CC BY 4.0.

Education in Britain took a halting step forward in the 1870s, but not without ruling class opposition

Universal education is a powerful force for workers’ emancipation. The 1870 Education Act was a great step towards achieving it, after being held back by the ruling class and churches.

By 1850 it was clear that Britain was not investing sufficiently in its people. In particular, mass educational provision had not been developed by the state. Schools still belonged mostly to the churches. Only very limited schooling was available to the people, all of it constrained by the country’s rigid class structure.

Other industrialising countries had already established a basis for universal education. Prussia had created a compulsory primary education for girls and boys as early as the 1760s. The United States of America was establishing a school system based on a common education by the 1830s.

From the late 18th century Britain was transformed by the industrial revolution and a massive growth in population. Churches were unable to provide either sufficient school places or proper education for all children. By the 1860s complacency about the state of education had become less acceptable.

Opposition

This disgraceful situation annoyed many who campaigned for more and better education, especially for the children of the working class. They met strong opposition from an upper class fearful of state control of education. The Liberal Party, influential and often in power, unashamedly advocated “the supreme virtue of limited government”.

Before 1870 elementary education in England and Wales was provided largely by the Church of England's National Society and the nonconformist British and Foreign School Society. But for many children the education they received was poor.

Britain’s industrial position in the world was slipping. The state of its education system compared poorly with its continental competitors. For example the Paris Exhibition of 1867 demonstrated a high level of industrial technique in other countries, particularly Germany. That level of development rested not only on a high standard of technical education but also on universal elementary schooling.

Grudging

The British government gradually and grudgingly acknowledged its responsibility for educating the people. Even then it only allowed educational expansion to proceed in a skewed manner that perpetuated class division and reinforced social separation.

In 1858 the government established a Royal Commission on the State of Popular Education in England. Its brief was to inquire into the state of public education and “consider what measures were required for the extension of sound and cheap elementary instruction to all classes of the people”.

‘A high proportion…failed to obtain a proper education.’

In 1861 under one in five of the 1.5 million children on the books of public elementary day schools run by the religious denominations were aged 12 or older. Attendance was irregular even for those in school; the majority attended for less than 100 days a year. And Commission surveys found that a high proportion of those whose attendance was more regular failed to obtain a proper education due to inadequate teaching.

In its 1861 Newcastle Report, the Commission rejected any suggestion that attendance at school should be made compulsory or that it should be extended. It claimed that the labour market required the employment of children.

Disagreement

The Commissioners disagreed about funding education. Some of them objected to government interfering with education on political and religious grounds. But they noted that “all the principal nations of Europe, and the United States of America, as well as British North America [ie what is now Canada], have felt it necessary to provide for the education of the people by public taxation”.

The Report recommended that a grant should be paid in respect of every child who, having attended an elementary school, passed an examination in the “three Rs” – reading, writing and (a)rithmetic. In 1862 the Revised Code of Regulations introduced a system of payment by results. This stipulated that every scholar for whom grants were claimed must be examined according to one of six standards in the three Rs.

There was much opposition to the Code. Teachers objected partly to the method of testing, but mainly to the principle of payment by results because it linked money for schools with the criterion of a minimum standard. Thus the higher quality primary work which was beginning to appear in the best elementary schools before 1861 was seriously discouraged.

‘The curriculum became restricted to get as many children through the examination as possible.’

The school curriculum became largely restricted to the three Rs in order to get as many children through the examination as possible. With very large classes rote learning and drilling dominated. Children had to learn their reading books off by heart. There was little incentive to either teach children the mechanics of reading or encourage a desire to read.

One contemporary head teacher said that the Code treated children’s minds as “specimens on a board with a pin stuck through them like beetles”. The Code’s strict conditions were gradually relaxed over the following thirty years because of such opposition.

School Boards

The 1870 Elementary Education Act (drafted by William Forster, a Liberal politician) divided England and Wales into about 2,500 school districts. They were run by School Boards elected by local ratepayers. These boards were to examine the provision of elementary education in their district. If there were not enough school places, they could build and maintain schools out of the rates. They could make their own by-laws allowing them to charge fees or, if they wanted, to let children in free.

The school boards varied greatly in size. London was the largest, while some rural boards controlled just one school. They were directly elected and independent of existing forms of local government. All ratepayers – including women – could vote for the school boards and stand as candidates to serve on them.

‘Many women were elected…when few other opportunities existed’

Contemporary accounts suggest that the Boards attracted high quality candidates keen to do public service. Many women were elected to this new sphere of public administration at a time when few opportunities existed for them in political or administrative life.

On the other hand Board elections were often subject to sectarian battles: between Church of England and nonconformists; between candidates pledged to educational development and those pledged to save ratepayers’ money; or between political parties. Some of the smaller boards in rural areas were controlled by people who had opposed their creation, and who aimed simply to restrict their activities.

Influential

The London board had 55 members and controlled almost 400 schools. It was not only the largest but also the most influential; the architecture and layout of its schools were widely copied. By the time it was abolished in 1904 it had almost 550,000 school places.

The London Schools Board buildings set standards for others to emulate. It established a system of school attendance officers. And it appointed its own medical officer to report on the ventilation of classrooms and to examine provision for children with special needs.

The Liberal government at the time, led by William Gladstone, was unwilling to make education secular. They strove to avoid confrontation with the churches. Forster's bill allowed six months for the religious societies to bid for funds for new schools. After that, school boards would be established to provide schools where they were still needed.

The government was also unwilling to make education compulsory. The 1870 Act gave school boards the power to enforce compulsion, but it did not make them do so.

In Scotland the path was different, although also heavily influenced by the churches. The Education (Scotland) Act in 1872 created boards that took over all the schools, enforced attendance and made limited provision for secondary education. But in other respects – rote learning and overcrowded classes – education in Scotland differed little from England and Wales in the late 19th century.

Secularisation

The Elementary Education Act of 1870 was an untidy compromise that produced a dual system of board schools and voluntary schools. But it did represent a step towards secularisation and state control and paved the way for further positive steps.

It banned denominational teaching in the new board schools, stating “No religious catechism or religious formulary which is distinctive of any particular denomination shall be taught in the school”. And parents had the right to withdraw their children from religious instruction.

The act made free or compulsory education possible, but only at the choice of local boards. It supplemented the voluntary religious schools, but did not do away with them.

State involvement

Above all the act It brought the state into action in education as never before. School boards were specifically empowered to support the education of the poor. It created in the school boards the most democratic organs of local administration of the nineteenth century.

On the other hand the act left opponents of school boards in positions of strength. It conceded education would have to be affordable and acceptable to the many sectional religious interests.

Overall the 1870 Act failed to resolve the problem of the participation of the churches in state educational provision. It chose not to begin separating church and state, as was happening in some other countries.

Church schools would continue to receive a maintenance grant of up to fifty per cent. But they would get no money for new buildings once the system was in place. Some assumed that this would result in a gradual decline in the number of church schools and their replacement by board schools.

Generous

The churches thought otherwise. They were determined to strengthen and consolidate their position. They took full advantage of the generous offer of government funds for new buildings. In the six months allowed, the Church of England and the Roman Catholic Church moved with great alacrity to plan as many as they could.

In just fifteen years, the number of Church of England schools rose from 6,382 to 11,864, and Catholic schools from 350 to 892. In the same period, the number of children attending church schools doubled to two million. The cost of sustaining this expanded provision was huge.

Yet, the churches overreached themselves: the initial impetus given to voluntary-school building could not be maintained. By the 1890s the number of voluntary schools fell by over 350, while the number of board schools rose by almost a thousand.

By 1900, nearly half the children who attended public elementary schools were in board schools, over 2 million pupils. In urban areas the proportion was often much higher. With all its flaws, the 1870 Act laid the first foundations of a universal system. Education was no longer a charity but a right.

Public Schools

The ruling class had advanced their own interests in the Public Schools Act (1868). It transformed the leading public schools and did away with many of their old foundation statutes and instituted new governing bodies.

This act removed the places which school founders had specified should be made available for “foundationers” – ie poor and deserving local scholars who received free board and education. Foundation scholarships were instead opened to competitive examination favouring pupils from preparatory schools.

Eton the model·

It also guaranteed the public schools as separate legal categories, founded on public funds but available only through fees, with Eton as the model. That amounted to a massive privatisation of public resources. The government manipulated the transfer of public endowments not just to the nine “great” public schools but also to many new public schools that opened in the ensuing period. Public schools were clearly defined as independent schools freed from control by any elected body.

‘The Public Schools Act systematised an entirely segregated system of education.’

The Public Schools Act systematised an entirely segregated system of education which had few parallels elsewhere in the world. It embedded separate schooling for the children of the governing class in upper class preserves uncontaminated by children of the working class. The classics, Latin and Greek, were preserved as the main core of teaching, ensuring the separation of public school pupils from others’ experience.

As the public schools expanded, their connections with Oxford and Cambridge universities strengthened. By the second half of the nineteenth century, more than 80 per cent of Oxbridge students were public school students; just 7 per cent came from local grammar schools.

In the years 1868 to 1870, despite some progress, the vested interests in Britain proved reluctant to take decisions leading either to major investment or transformations in educational provision to benefit the whole people. This has continued to be the case in all subsequent periods. We still suffer the same crippling lack of vision.

A shorter, edited version of this article appeared in the May/June 2020 edition of Workers