3 December 2019

George Cruickshank’s famous cartoon of the massacre. The speech text reads: “Down with ‘em! Chop em down my brave boys: give them no quarter they want to take our Beef & Pudding from us! ---- & remember the more you kill the less poor rates you'll have to pay so go at it Lads show your courage & your Loyalty.”

Two hundred years ago, 18 people were killed and 654 injured participating in a peaceful rally calling for the reform of a corrupt parliament...

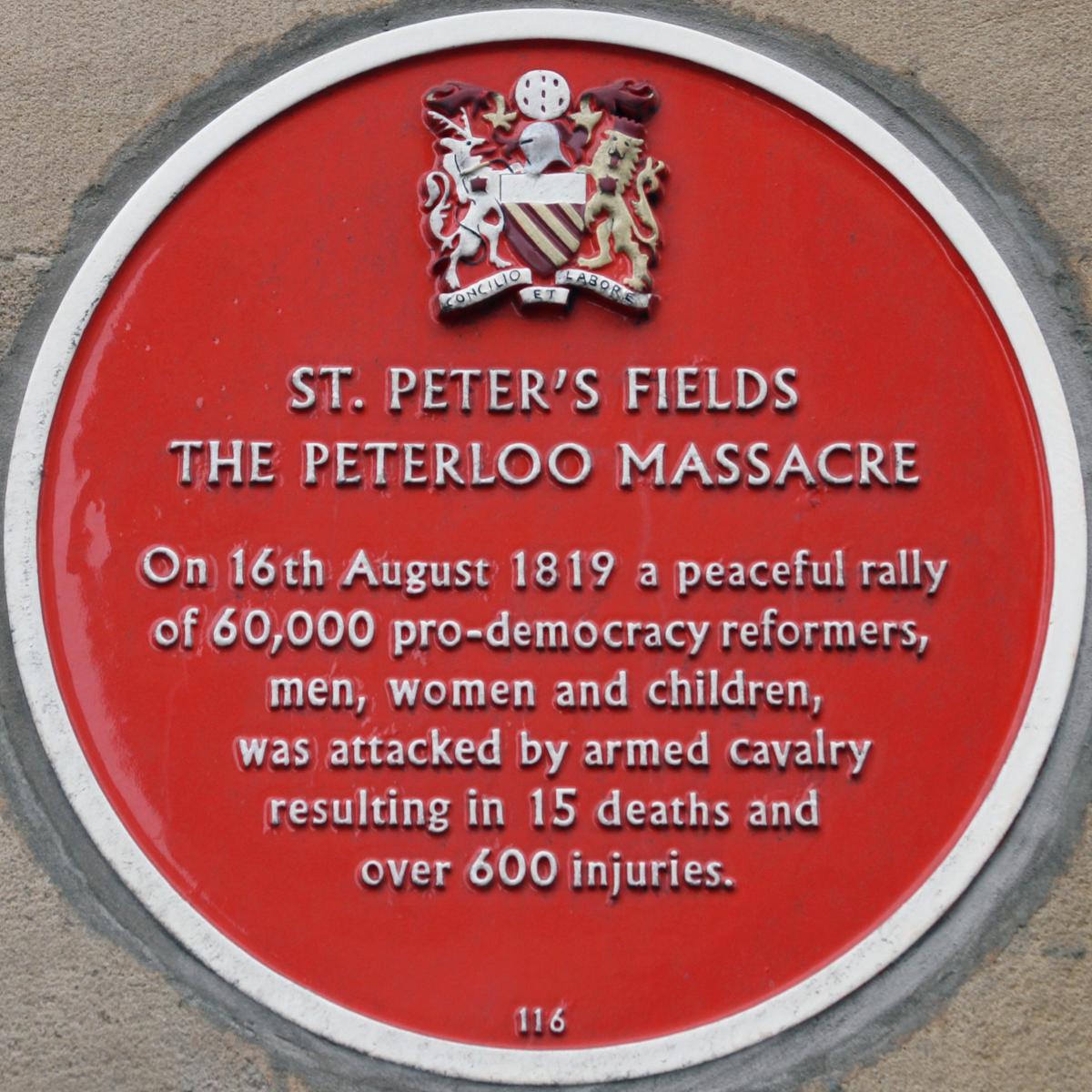

On 16 August 1819 80,000 men, women and children – peaceful and unarmed demonstrators – converged for a meeting in the centre of Manchester. Walking in impressive contingents from surrounding towns and villages they gathered on open land in St. Peter’s Field.

Throughout industrial Lancashire, a combination of clever organisation and widespread publicity had combined to produce the biggest demonstration ever seen in the country. Some contemporary newspapers claimed there were far more than 80,000 people present.

Yet, just after the start time of 1pm, the local magistrates sent in soldiers from the 15th Hussars together with volunteer cavalry from the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry to arrest the main speaker Henry Hunt and disperse the demonstration.

The result was the worst violence ever to occur at a political meeting in Britain. 18 died and at least 654 people required medical treatment. A quarter of the casualties were women.

Imprisoned

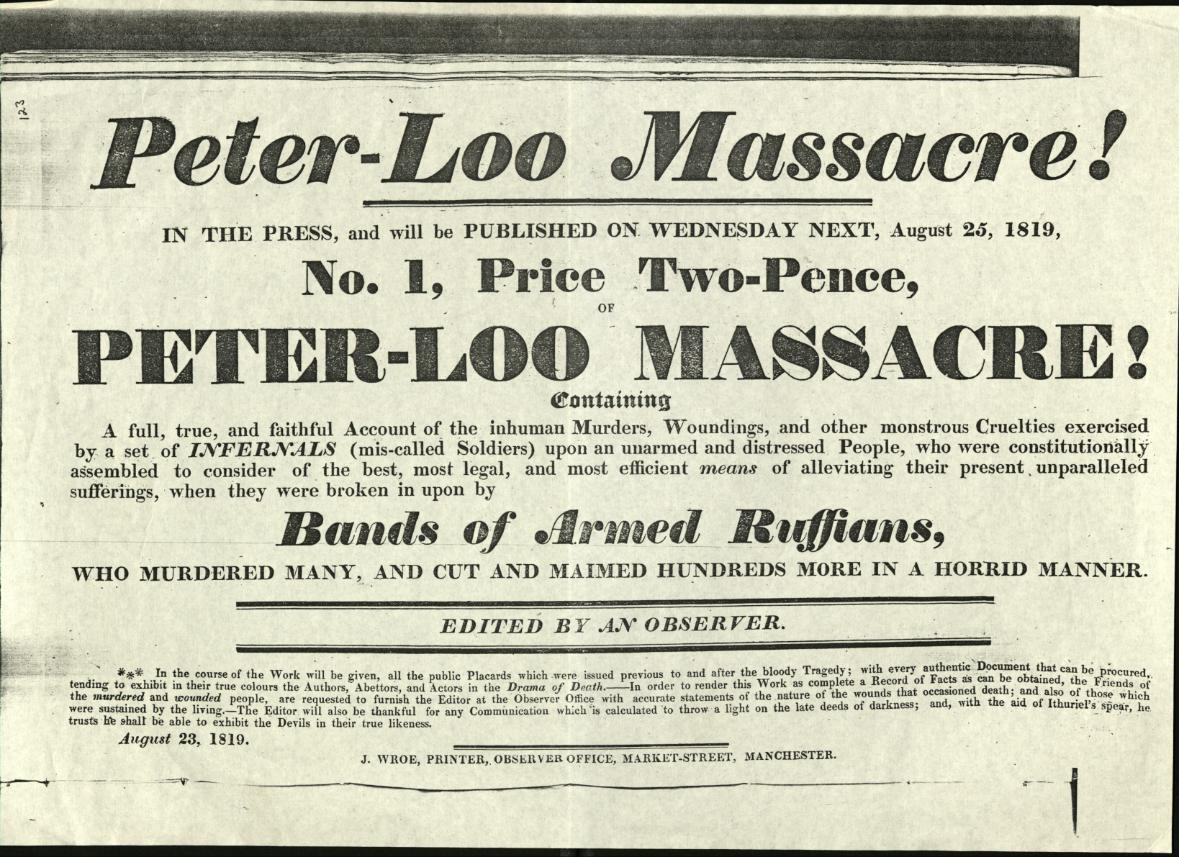

The event was immediately labelled the “Peterloo” Massacre by James Wroe, a journalist at the Manchester Observer newspaper, in punning reference to the battle of Waterloo four years earlier. The name has deservedly stuck. Wroe was himself imprisoned for a year and his newspaper closed down by the authorities in retaliation.

‘This armed assault was rooted in the clash of classes…’

This appalling armed assault on defenceless workers was not an isolated event. It was rooted in the clash of classes. An arrogant ruling class was unwilling to change its policies in the face of great social distress or to give up any of its political and economic advantages. An emerging working class was beginning to find its voice; unprepared it believed in the power of reason to make progress.

Britain was going through a time of dramatic change and social upheaval; from an agricultural to an industrial culture, from a rural to an urban environment. The fortunes of working people deteriorated around this period, particularly after the end of the war against France in 1815.

Industrial revolution

Lancashire had been totally altered by the industrial revolution. Small time cotton manufacture had existed since the beginning of the seventeenth century, centred around Manchester and surrounding villages such as Oldham, Middleton, Rochdale and Royton.

Merchants bought raw cotton from Liverpool dealers, sold it to small-time masters who in turn sold it to spinners working in their cottages. The yarn was spun and sold back to the masters or hand-loom weavers, who wove the cloth as a finished product for sale.

Everything changed in the 1770s. Mechanical inventions coupled to the power of steam meant that high quality cotton could be produced in previously unimaginable quantities. These developments led Lancashire to become “the cradle of the Industrial Revolution”. Capital poured into the county, making massive fortunes for some.

Manchester soon grew from a town to the second largest city in England. Around it, villages were turned into cotton towns. For example Oldham with less than 1,500 inhabitants in 1750 had grown to 50,000 by 1816. While the traditional wool industry faded and declined, cotton exports soared from a mere £355,060 in 1780 to £27 million in 1819.

The new spinning processes were concentrated in mills. By 1815 there were sixty factories in the Manchester area, employing some 24,000 workers. Over 90 per cent were spinning mills.

Harsh conditions

Conditions were harsh both to increase profit for the master and to keep workers submissive. Spinners – men, women and children from the age of five – worked a 14-hour day in temperatures of over 30 degrees Centigrade. They were heavily fined for quite trivial offences.

The war with France and the cessation of army clothing contracts at its end had undermined the cotton bandwagon. Wages dropped in the mills and the remaining cottage-based industry.

Adding to hardship, in 1815 the Corn Laws imposed tariffs and restrictions on imported food and grain. They blocked the import of cheap grain and kept grain prices high. By favouring domestic producers, this enhanced the profits and political power of the great landowners.

When the terms of the Corn Laws bill became known, there were riots and protest meetings throughout the country. And when it eventually passed into law, the House of Commons was ringed by troops with bayonets fixed.

No democracy

Inspired at first by economic injustice, the Corn Bill protests soon led to a questioning of the basis of governance in the country. The people then had no say in the election of parliamentary representatives. Working people had no vote. Britain had not even the pretence of democracy.

Manchester had no member of parliament. Birmingham, Leeds and other fast rising industrial cities were also unrepresented. At the other extreme “rotten boroughs”, most famously Old Sarum, had not a single voter. And outrageous forms of bribery and patronage were the norm.

A dreadful harvest in 1816, known as the year without a summer, saw the price of bread and other food rocket, whilst wages didn’t. Increased distress led to more people joining the Hampden Clubs. Initially founded in London, they promoted radical reform and spread widely in Lancashire in early 1817.

There was talk of universal suffrage to allow everyone to participate in the governance of society; of equal representation not based on property; of reform of the corrupt Houses of Parliament; of the source of all legitimate power being the people. Open air meetings became popular to spread the message. Some were held on the moors, with watching soldiers in attendance. To the shock of many, women attended in great numbers.

Repression

Early in March 1817 the government suspended habeas corpus, removing safeguards against detention without due cause. It falsely claimed evidence of a revolution against the government and hailed repressive measures as necessary for the good of the country. This had an effect; fewer mass meetings were called and the Lancashire Hampden Clubs fell away. The conservatively-minded radical William Cobbett fled to America fearing imprisonment, where he continued to publish his papers.

A genuinely working class movement arose called the “Blanket March”, though fleeting and without financial backing. It was a response to the economic distress of workers and their families in the clothing industry. Cotton spinners were the main supporters, though some weavers were also involved. Volunteers proposed to march from Manchester to London with a petition to the Prince Regent. The Radicals did not approve or participate in the scheme.

On 10 March 1817 between 10,000 and 30,000 people assembled on Saint Peter’s Field, Manchester. The magistrates read the Riot Act as the leaders were addressing the crowd, surrounded the platform and arrested them. The crowd dispersed. Shortly after the Blanket March actions, the cavalry of the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry was formed; a sign of the times.

Later that month the government fabricated stories about an insurrection plot, known as the Ardwick Conspiracy. There were further suspensions of habeas corpus and arrests of Radical leaders, who mostly did not approve of or participate in the Blanket March. Generally they were interrogated but not charged. Eventually many were released on bail as the Privy Councillors were unable to prove high treason or anything else.

There was a burgeoning trade union movement too. The spinners with a small number of highly skilled jobs led calls for improved conditions and higher wages. The government employed spies and agents provocateurs to spy on these industrial workers and to stir up trouble.

Strikes

In 1818 yarn prices had risen but the masters refused to honour an increase in wages. That became a year of strikes in Lancashire, particularly by spinners. There was no strike pay; the strikers lived on accumulated subscriptions paid into Benefit Societies, support from other trades not on strike and sympathetic donations.

The Combination Acts, passed in 1799 and 1800, had made combinations of working people illegal, including trade unions. By 1818 many parts of the Combination Acts were almost a dead letter. There was no way of stopping a strike short of sending in the military. The magistrates could not for a while find a way to interfere in the 1818 disputes; the strike lasted into September.

Finally leaders were arrested and striking spinners without funds and without food had to capitulate. As the spinners’ action ended, the hand-loom weavers started a strike. Even the magistrates urged the masters to pay this increase as the weavers’ wages were so low. But a majority of the masters refused to pay up.

All of these setbacks on pay turned the weavers and the spinners towards the Radicals, who argued optimistically that the repeal of the Combination Acts and the Corn Laws were inevitable once parliamentary reform had been achieved. Open air meetings in the cotton towns and on the moors increased. Union Societies, dedicated to educating workers, blossomed.

Agitation for reform

Repression of the textile strikes of 1818 strengthened the efforts of the Radical reformers. In face of prosecution and military force, striking weavers and spinners joined the agitation to reform Parliament. Despite laws passed in 1817 to restrict political activity, huge meetings were held throughout the industrial districts of Lancashire and Yorkshire.

Hopes were high for a reformed parliament, and that it would do away with all manner of evils. The list was long: bribery and corruption at elections; parliament full with placemen from privileged backgrounds; the secret service and its ubiquitous spy network and so on. Reformers wanted a reform of the legal system; to cut down the Civil List supporting the Royal Family and to reduce taxes. Radicals proposed annual parliaments and voting by ballot, as well as repeal of the Corn Laws. The cry of “No taxation without representation” appeared, echoing the Americans over forty years earlier.

The British economy was struggling after 22 years of war with France and others from 1793 to 1815. The cost was immense – over £800 million, or £3 trillion at current values. Growing industrialisation underwrote much of this, which helped to ensure military success. But the switch to a peace-time economy and the level of debt caused economic problems.

There was mass unemployment, deprivation and frustration, but even given the distress little real sign of mass insurrection. At this time the government had no large standing army or central police force to suppress revolt or revolution.

'The government had to uphold the status quo at all costs...'

The Tory government led by the Earl of Liverpool was unmoved. It was one of the most reactionary and repressive in British history. The government claimed without any solid evidence that Britain was on the brink of revolution and so the status quo had to be upheld at all costs to prevent another French Revolution breaking out here.

Liverpool’s administration, believing or pretending the country was on the brink, used magistrates as its enforcers. These were chosen by the Crown on the recommendation of the Lord Lieutenants of each county. In addition to administering local “justice”, magistrates were able to call upon the regular army and local militia in “times of unrest”. They also read the Riot Act and ordered the dispersal of “mobs” in such periods. They kept the government informed of what going on in their areas. In effect magistrates defined what were “times of unrest”.

Spying

Magistrates employed spies to inform them about what was taking place in factories, public houses and clubs. Much of the information supplied was dubious or unsubstantiated. But magistrates reported the information to the Home Office anyway. Lord Sidmouth, the Home Secretary, also despatched his own spies to snoop around the unsettled manufacturing districts. Unsurprisingly there was an in-built tendency for spies to exaggerate because “no sedition meant no pay”.

The Manchester magistrates were landowners, clergymen, business owners and men of property, tending to be High Anglican, High Tory, and unsympathetic to reform. An unwritten rule was that no manufacturer could serve on the bench. The magistrates were generally hated by industrial workers and Radicals alike.

By mid-1819 the cotton trade was almost at a standstill; the weavers’ plight had reached a new level of desperation. Radical activity erupted in the towns and drilling on the moors took place to forge a discipline for the mass parades on the way to rallies. By the end of July as many as 2,000 people around Manchester were parading.

The meeting at St Peter’s Field on 16 August was called in support of “the most speedy and effectual mode of obtaining Radical reform in the Commons House of Parliament”. This demonstration was a Lancashire rally, not just a Manchester one. After a long period of economic hardship and political suppression the working class had many grievances; no wonder the meeting was well supported.

Plans were made. Each surrounding village was given a time and place to meet, from which its members would proceed to bigger towns before all were to coalesce in Manchester behind numerous bands and self-designed banners.

Alarm

Before the rally, the government established “A Committee in Aid of the Civil Powers”, which considerably heightened alarm. Previously the government had alerted Yeomanry Corps around the country, including the cavalry of the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry.

There had been a two-year build-up of hostility between the yeomanry and the populace. Quietly, prior to Peterloo, they had sent their sabres to be sharpened. Also, a proclamation in the Prince Regent’s name condemned, though did not ban, seditious assemblies and the practice of drilling. A few days before the St. Peter’s Field meeting Henry Hunt, the principal speaker and prominent radical, checked with the local magistrates that it was legal and could go ahead. They told him it could.

The demonstrators brought “no other weapon but that of a self-approving conscience”. As the crowds reached central Manchester, they were in good humour. Once they were packed inside St. Peter’s Field, Hunt arrived and mounted the platform. He was known as “The Orator” for his stirring speeches at mass meetings.

Yeomanry sent in

Immediately the magistrates ordered Manchester’s corrupt and much feared deputy constable to arrest him. To help him they sent in the yeomanry, who clattered into crowd and arrested Hunt who was physically abused as he was led away. The magistrates now sent in the 15th Hussars too. The crowd fled trying to avoid the flashing blades and horses’ hooves.

Within 20 minutes the field was empty save for bodies and the discarded debris of the rally. The troops rallied in front of the magistrates’ building and gave three cheers. Later the Prince Regent, soon to reign as George IV, sent a message commending their “preservation of the public tranquillity”. The chief magistrate William Hulton wrote to Lord Sidmouth praising “the extreme forbearance of the military”.

‘It took a century and more for the ruling class of our country to concede some aspects of parliamentary reform…’

Afterwards the magistrates claimed they had read the Riot Act, the formal procedure necessary to order the dispersal of a crowd, but no one heard them. And they certainly did not allow the statutory hour for the gathering to leave. Hunt was sentenced to two and half years’ imprisonment for “seditious assembly”.

Despite the loss of life and subsequent protests, Peterloo did not immediately affect the way parliament was run. Towards the close of 1819, a further and more drastic set of repressive measures was passed called the Six Acts which (1) equipped the magistrates with more drastic powers in dealing with offenders, (2) prohibited drilling and the use of arms, (3) strengthened the laws against blasphemous and seditious libel, (4) gave the magistrates the power to search private houses, and to confiscate weapons, (5) restricted still further the right of public meeting, and (6) subjected the periodical pamphlets published by the radicals to the newspaper tax, with the object of preventing cheap publications.

Suffrage

It took a century and more for the ruling class of our country to very gradually and very reluctantly extend the suffrage and concede some aspects of parliamentary reform through acts in 1832, 1867, 1884, 1918 and 1928. Generations of rulers were probably surprised at their ability to preserve the dominance of capital and to contain the potential of working people during this journey, even with universal suffrage.

We are still discovering today in the battle raging for Brexit and independence, how we must defeat the rotten corruption in the parliamentary edifice that still strives to hem us in. We are still learning from the past experience.

A shorter version of this article was published in Workers November/December 2019 edition.