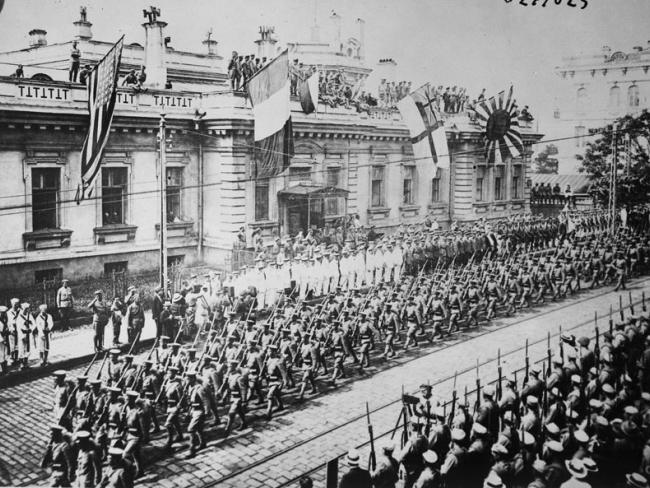

Interventionist soldiers in Vladivostok, 1918. Photo National Archives at College Park, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

After the bloody world war between rival imperialisms, the British ruling class and its allies turned their attention to the infant Soviet Union…

Days after the Russian October 1917 revolution, the Cossack government of the Don Territory offered refuge to Kerensky’s deposed Provisional Government, “to organize a struggle against the Bolsheviks”. That was the first action against the Bolshevik government, in which Britain and its allies played a leading role.

The British government had backed one coup after another, most significantly, in September 1917 by the army’s commander-in-chief General Lavr Kornilov against Kerensky. It failed, but in effect it was the start of the civil war in Russia.

Lenin wrote at the time “…the Kornilov revolt was a military conspiracy supported by the landowners and capitalists led by the Cadet Party, a conspiracy by which the bourgeoisie has actually begun a civil war.”

The first interventionist forces arrived a few months later in March 1918 – with 130 Royal Marines at Murmansk in North Russia. Many more followed. By mid-July, the Allies had committed themselves to waging a full-scale offensive campaign.

On 20 July, British forces moved to occupy Archangel, the first open Allied offensive. They backed the local White Guard (anti-Bolshevik) revolt and overthrew the local Soviets. By the end of the year 14,000 troops were there, from Britain, the USA, France, Italy and Serbia.

As the Allied war against Germany ended in November 1918, the Soviet government was still in power, defending Russia’s national independence. When it was clear that the German army was beaten, the Soviet government offered to negotiate peace with the Allies

‘The Allies and their White Russian friends committed war crimes on a vast scale, only ever matched by Hitler’s later assault. …’

But the Allies rejected this peace proposal. Instead the British government organised and led a much bigger invasion force into Russia – eventually some 180,000 Allied troops (60,000 British) from sixteen countries across six fronts. And in addition 70,000 Japanese troops intervened in Siberia.

Britain publicly pledged that “the domestic policy of Russia is a matter for Russia alone.” But in reality British rulers intervened extensively. Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs Lord Robert Cecil told the War Cabinet that really a military dictatorship would be necessary.

Then came Admiral Kolchak’s coup in Siberia on 17-18 November 1918, when he declared himself ‘Supreme Ruler’. Churchill, then minister for munitions, boasted in Parliament that the British Government had called this into being – of necessity.

One of Kolchak’s generals, Rudolf Gajda, said of his government, “…[it] cannot possibly stand and if the Allies support him they will make the greatest mistake in history.” He went on to say that one half of the government was making plans for a constituent assembly, and the other was plotting a restoration of monarchy. Calls for an assembly were actually cover for violent counter-revolution.

British bullets

The Whites always depended on outside help. General Alfred Knox, Britain’s military adviser to Kolchak, is reported to have said, “Since about the middle of December every round of rifle ammunition fired on the front has been of British manufacture, conveyed to Vladivostok in British ships and delivered at Omsk by British guards.”

In October 1919, Kolchak’s forces put down a workers’ rising in Omsk, killing an estimated 900-1,000 people, including the last members of the Constituent Assembly – twelve moderate Socialist Revolutionary politicians.

The British government sabotaged peace negotiations. General Knox denounced the very idea of talks with “the blood-stained, Jew-led Bolsheviks”.

The British Military Mission to South Russia reported that the White recovery under General Denikin after March 1919 “was due almost entirely to British assistance”.

Although British forces in South Russia were supposed only to be training and supplying, they did much more. 47 Squadron of the RAF helped the Whites hold Tsaritsyn for six months, strafing enemy troops and bombing trains. Ministers routinely lied to parliament that they had orders not to join in combat.

The Allies and their White Russian friends committed war crimes on a vast scale, only ever matched by Hitler’s later assault. Allied officers instructed their soldiers “…to take no prisoners, to kill them even if they came in unarmed.”

Churchill was well aware of the Whites’ massacres of Jews, but denied all the reports, claiming that in White-held territory “protection was always accorded to the Jewish population”. Stopping military aid, he warned, would deprive Britain of the leverage to “exercise a moderating influence”.

In the Sunday Herald, Churchill asserted that “International and terrorist Jews were plotting worldwide revolution.” The White conviction that Jews masterminded the Revolution fed into Nazism via émigré organisations in Munich and Berlin.

The British government had spent £100 million on the war. The war killed 1.35 million Russians and crippled three million. Another 14 million people died of starvation, cholera, typhus and “Spanish flu”.

The war became ever more unpopular among British workers. They called strikes, refused to load war munitions, and set up Councils of Action. The TUC set up the Hands off Russia Committee. All this helped to force the government to end the intervention.

The last British troops left North Russia in October 1919, without the traditional, face-saving “decent interval” after abandoning their “allies”. Russia’s workers and peasants defeated the joint armed attack. The newly formed Soviet Republic won its independence.