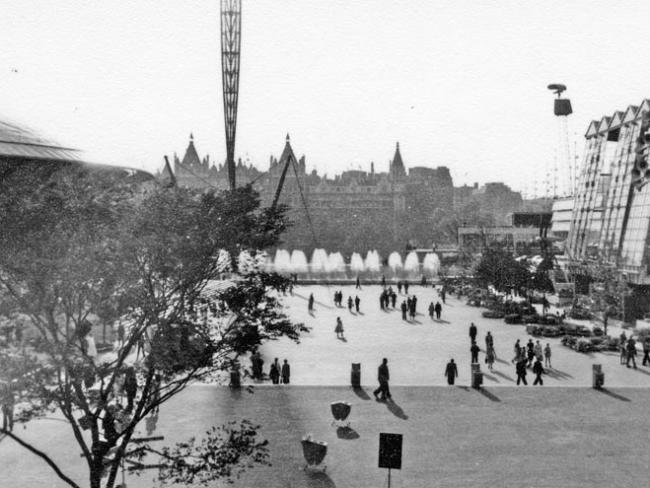

The Festival of Britain site with the iconic dome (left) and Skylon (centre). Photo Ben Brooksbank/geograph.org.uk (CC BY-SA 2.0).

Seventy years ago, in the midst of post-war austerity and rationing, Britain found the will to create a remarkable, popular festival…

Post-war Britain was beset by problems. For the majority of people, life was hard and difficult. The daily routine was still making do on very little. The euphoria of victory in Europe had long since given way to a more humdrum existence.

Proposed in 1943, the idea of a festival initially attracted much opposition. But in late 1947 the government decided to go ahead and set up a Festival Council with a broad yet specific brief for “a national display illustrating the British contribution to civilisation, past, present and future in the arts, science and technology and in industrial design”.

Journalist Gerald Barry headed the planning. He was a firm believer in putting the modernist architect at the centre of post-war reconstruction and had faith in economic and social planning. Barry acted swiftly to employ a large number of talented, young people, mostly left free to come up with ideas.

The festival was expected to meld education, inspiration and pleasure, and expose fresh ideas to a wide audience. It would give commerce and the arts in Britain a chance to show what they could do. It was to be “a tonic to the nation”, celebrate our recovery from the war and demonstrate that Britain had within itself the talent, imagination and energy to create a new society.

The selected site lay between County Hall and Waterloo Bridge on the south Bank of the Thames. It was soggy and derelict, but centrally placed with good communication links, close to iconic London landmarks. And as a bonus, the London County Council (using its own funding) already had the go-ahead for a new concert hall to be opened there in 1951. Work began immediately on a wall to protect the area from flooding.

The team planned to create a commercial and cultural showcase of Britain; a display spectacle of the mechanical wonders of the age, of futuristic designs and bright colours to offset the drabness of war and postwar austerity. It was an assertion that, having won the war, the British people were not about to lose the peace.

A slender steel and aluminium structure in the shape of an outsized exclamation mark – Britain’s first high-tech piece of architecture – was selected to represent the festival. Named the Skylon, it rose 90 metres in the air and was seemingly free-standing and defying gravity, though held in place by high-tension cables slung between three steel beams. Lit from inside, at night it could be seen all over London.

Bold

The festival’s icon was the pancake-shaped Dome of Discovery. With bold, clean lines, light and space, it combined practicality and beauty to house and display the best of British invention and enterprise.

The dome was 110 metres in diameter with a smooth metal cover of aluminium alloy, a material not often used for substantial buildings at that time. The ribs underneath were supported by a steel box ring girder, itself held 12 metres above ground by a series of slender lattice steel masts. To many children familiar with futuristic space comics, it looked pleasingly like a flying saucer.

‘It was an assertion that, having won the war, the British people were not about to lose the peace…’

Over 10,000 products of British enterprise were judged worthy of display – ranging in size from locomotives to lipsticks and in value from many thousands of pounds to a few pennies. In 1951 washing machines, water heaters, fridges, vacuum cleaners and electric irons were beyond the experience of well over half the population.

Pavilions dedicated to land, agriculture, mining and industry in the story of Britain surrounded the Dome. Elsewhere the themes were more about people – arts and crafts, education, depictions of the “British at Home”, their recreations and, trickier, their character. The river front was given a seaside makeover – a promenade, deckchairs, ice cream stalls and, optimistically, sunshades.

Overall the small site was planned so as to give a sense of space and allow for easy, leisurely movement between the pavilions. This feel was achieved by a series of connecting patios, each of contrasting shapes and colours, with new points of interest to catch the eye at every turn and an imaginative use of glass giving a transparency to buildings.

Poplar housing

More space was required, in particular to show what could be achieved with socially motivated architecture. A site was selected in Poplar in order to create a purpose-built, lower living-density environment for 1,500 residents in a village-like community. This Lansbury Estate had its own schools and church, an old people’s home, a pedestrian shopping centre, covered market place, pubs and open spaces.

Also, a new wing was built at the Science Museum in Kensington with its opening exhibition exploring the scope of the scientific revolution.

The Lion and the Unicorn pavilion, while probably promoting an artificial national self-image, was simply dotty and became one of the most popular festival features. Its odd name was supposed to represent two opposing facets of the British character – the stolid, unimaginative Lion and the highly individualised, eccentric, unpredictable Unicorn.

A public appeal for models made of unlikely materials or machines built for unpredictable purposes resulted in a delightful, bizarre collection of exhibits.

More land was acquired to develop Battersea Fun Fair and Pleasure Gardens with lots of entertainment and landscaped areas. A river shuttle service connected this venue to the main festival. Eight and a half million people visited both sites.

• A longer version of this article is on the web at www.cpbml.org.uk