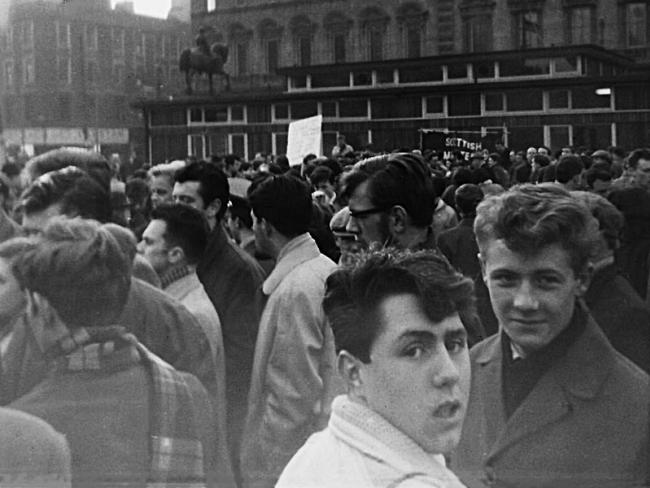

Young men demonstrating against conscription in George Square, Glasgow, February 1963. Photo Workers.

Sixty years ago the youth of Britain made it clear that they would not be forcibly enlisted in the armed forces…

As the build-up of NATO forces in Europe continues, its member countries are increasing military spending and the number of personnel in their armed forces. Ten of the 32 NATO members already have conscription. Others are set to follow.

On 17 June this year the US House of Representatives passed a bill requiring men aged from 18 to 26 to be automatically registered for draft conscription. And just weeks before, Rishi Sunak set out plans to introduce national service for 18-year-old males and females. Would a Starmer government pursue that plan?

The media have set this warlike mood – as The Independent put it, “Britons face call-up to armed forces if UK goes to war with Russia.” And on BBC News we saw, “UK citizen army: Preparing the ‘pre-war generation’ for conflict.”

Militarisation

Is it possible to resist the militarisation of society, the road to war and the drafting of younger generations into the armed forces? How do we stop militarisation and keep Britain out of war? One answer is that youth are quite capable of not only acquiring the skills necessary to work in a Britain revived industrially and culturally, but also of taking a leading role in developing such opposition.

Agriculture too could use their energy and lead to more self-sufficiency and shorter supply chains that would improve national security. As journalist and farmer Jeremy Clarkson said when urging young people to learn where their food comes from, “Conscription is an idiotic idea – volunteer for the farms instead!”

Mass conscription for British armed forces in World War One was introduced in 1916 as volunteering and enthusiasm for fighting fell off. That led to resistance from conscientious objectors and “war resisters”.

‘The Labour Party was goaded into appearing to support conscription…’

Conscription ended in 1920 but was fully revived in 1939 at the outbreak of World War Two when there was clearly a threat of invasion. But then it continued for a long period afterwards. The Labour government introduced peacetime conscription in 1948. The service period was later extended in October 1950 due to Britain’s active involvement in the Korean War.

Military campaigns against various struggles for colonial freedom continued thought the 1950s. Conscripts saw action in Malaya, Cyprus, Kenya, Aden and Borneo as well as in the 1956 Suez Crisis. Conscription formally ended in December 1960. The last conscripted serviceman left the British armed forces in May 1963.

Harold Macmillan, the Conservative prime minister, resigned in October 1963 in the wake of the Profumo affair, but his party hung on in government until the general election a year later. Whether as a distraction or through real need, their policy discussions during that period frequently cited the armed forces as being under strength – raising the prospect of reintroducing conscription.

Alarm

They goaded the opposition Labour Party into appearing to support conscription, pointing to that party’s then opposition to nuclear weapons. All of this talk caused alarm among young men who were not minded to be drafted.

Britain’s commitments to NATO at the time included contributing 55,000 personnel. Speaking in parliament on 5 March 1964 in a debate about the size of the Army, the war minister James Ramsden pointed to the difficulty of providing such numbers.

Referring to the total army strength of 171,588 at that time he said “We have got to make good the shortages and especially build up the infantry”. The resolution passed that day called for an army strength of 229,000. Antagonism to the USSR featured in the reasoning, as well as involvement in colonial conflicts.

Marcus Lipton, Labour MP for Brixton, saw no problem. He said “…what we need is 30,000 men a year more than we have at present. Some 370,000 men reach the age of 18 every year, and if it were possible by some easy, simple device to pull 10,000 out of the 370,000 and put them in the Army, the problem from the point of view of the Minister of Defence and the Secretary of State for War would be very much simpler.”

But Emrys Hughes (Labour MP for South Ayrshire, a conscientious objector in WW1 and a critic of his party’s policy on war) wasn’t keen. He had pointed out, referring to the forthcoming general election, “But then we hear that after the election, when one of the parties is in power, there is to be some kind of gentlemen’s agreement, as my hon. friend the hon. Member for Dudley [George Wigg, later a Labour minister and peer] calls it, under which the two parties will unite in imposing some kind of selective service on the people.”

Is such collusion happening today? A year of such talk was enough to galvanise the youth of 1964 into action. A slogan advertising a demonstration against conscription, written with a block of chalk on the sandstone wall of the Western Infirmary in Glasgow remained there for over 50 years, fading gradually.

Turnout

Chalked by a short-lived organisation Youth Against the Bomb, it simply said “No Conscription – George Square Sat October 10th”. A sizeable turnout filled the central square, a mixture of youth and trade unionists, many with experience of protesting against the presence of American nuclear bases on the Clyde during the previous few years. Similar protests were held around Britain.

That demonstration was five days before the Harold Wilson Labour Government assumed power. Pressure continued and conscription never saw the light of day. We may need the same simple clarity of those protesters again.