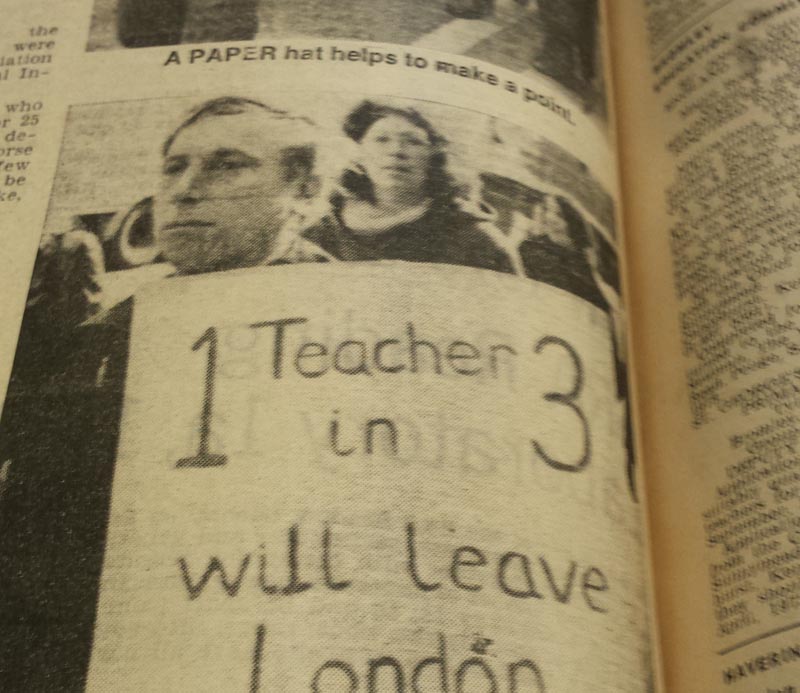

29 April 1974: London teachers on the march for a London allowance. Photo Keystone Pictures USA/Alamy Stock Photos

Astronomic rises in house prices and rents, young teachers unable to live in the capital, a staffing crisis in the schools. Sounds familiar?

In the early 1970s teaching staff turnover in London schools was running at a record 30 per cent annually – higher in certain areas. Young teachers were finding it nearly impossible to live in the capital. Living costs were huge and the burden of housing costs and fares was crippling.

House prices and rents were especially prohibitive for young teachers, who were the bulk of the teaching force. Houses in London cost 50 per cent more than in the provinces. Rents were equally high. Many young teachers were leaving the capital, resulting in teacher shortages and difficulties in running schools properly.

The London Allowance had been unchanged since 1970, and inflation was high. In May 1972, an arbitration tribunal said the allowance should rise on 1 November. But then the Conservative government imposed a wage freeze from that month.

At the time teachers still enjoyed collective bargaining through the Burnham Committee, which brought together representatives of the employers and the teacher unions. When teachers put their case for a £300 allowance (up from £112), the leader of the management panel said they were substantially in agreement with the arguments.

Intervention

Everyone seemed confident an agreement would have been made. But the Secretary of State intervened, dictating a paltry offer in keeping with the wage freeze. Teachers knew that the government had deliberately manoeuvred negotiations into the period of the wage freeze.

The NUT Action Committee called for a half-day strike of all London teachers on 23 November against the government’s decision to prevent the Burnham Committee from making a realistic offer for the London Allowance.

At a meeting at Westminster Central Hall called jointly by London NUT bodies, more than 1,000 London teachers had overwhelmingly voted in favour of the strike in defence of their living standards, their schools and the children in their care. It was well supported. Despite a train strike, more than 12,000 teachers marched on the day.

‘The education service in London was nearing breakdown.’

On 3 February 1973, the NUT Executive called further strikes in London schools. They aimed to persuade the government to allow free negotiations and to exclude the London Allowance from the national salary cap. London teachers were not prepared to accept an increase at the expense of their colleagues throughout the country. They knew the government was hoping to split London teachers from their colleagues.

A series of 3-day strikes took place in three waves during February and March 1973. The choice of participating schools was made according to the strongest results and returns in the ballots. Teachers rushed to join the NUT.

In the first wave, 1,360 teachers were withdrawn from 97 schools in outer London boroughs, who had balloted 91 per cent in favour; 79 schools were closed. The second wave focused on inner London, involving a greater number of teachers and schools. Strikes were staggered for maximum impact. Striking teachers took part in local campaigns to gain maximum publicity.

The third wave was held back to see if progress was made in talks. When nothing materialised, it went ahead at the beginning of March. 2,775 teachers came out in 212 schools affecting more than 83,500 children. All over London local marches and strike meetings were held and leaflets distributed. More than 2,500 striking teachers marched through central London.

Pay freeze

Prime Minister Heath told the NUT the London Allowance must be subject to the pay freeze. In response, the NUT called a one-day strike of all London teachers on 22 March – involving 36,000 Inner London teachers, plus those outer London boroughs covered by the London Allowance payment. More than 20,000 teachers marched through central London in the biggest march of London teachers ever, before lobbying parliament. Nearly 1,500,000 children were affected. In the Inner London Education Authority area alone, 271 schools were closed and 291 were partially closed.

Despite the action and the worsening situation in schools, the government would not give ground. The NUT waited for a decision from the Pay Board.

The Council of the Inner London Teachers Association called on the NUT to support members who refused to carry out extra duties because of staff shortage. This was about to worsen in the 1973 autumn term because the school leaving age had just been raised to 16. Soon this tactic became an NUT national instruction to members and London schools were introducing part-time education for 20,000 students. The education service in London was nearing breakdown.

No mention

When the Pay Board report finally appeared in late September, it failed to mention the London Allowance at all. Two government ministers had earlier advised the NUT to go to the Pay Board in the hope that the allowance would be treated as an anomaly to be rectified. Teachers were incensed. The government then asked the Pay Board to carry out an enquiry into all aspects of London Allowances for all public employees. But those findings were not due until the end of June 1974.

In October the teachers’ side and employers’ side of the Burnham Committee jointly asked Education Secretary Margaret Thatcher to introduce a special change to the Pay Code in view of the crisis in London schools. They pressed for an immediate and substantial increase in the teachers’ London Allowance. But Thatcher was intransigent; she had cast herself in the role of Nero, fiddling while London burned.

By the beginning of January 1974, about a third of inner London secondary schools were sending children home. The NUT was not prepared to accept the teacher shortage in London and continued refusing to cover unfilled vacancies. By the beginning of February, 31,000 children were being sent home each week. Leaflets were prepared for parents to explain why.

A Labour government took over in March 1974 but the new Cabinet had no willingness to solve the dispute. Employment Secretary Michael Foot addressing the NUT directly said, “I can’t make an exception to you regarding the interim payment.”

At the NUT Easter Conference, Education Secretary Reg Prentice said, “London strikes will not move me”. An Executive motion called for a referendum of London members to find out for how long they were prepared to go on strike in support of the London Allowance claim. On 29 April London NUT members struck for a half day and lobbied parliament. 15,000 London teachers were on the march. Prentice did not meet with teachers at the lobby.The NUT referendum showed considerable willingness to take further action. But the NUT Action Committee reserved the possibility of action until after the release of the Pay Board Report at the end of June. By this time nearly 23,000 London teachers had already resigned their posts for the following academic year. The outflow of teachers and subsequent staff shortages showed no sign of easing.

At last, the Pay Board suggested two London Allowance payments: £400 in inner London; £200 in outer London. But the inner London payment was restricted to within a 4 mile radius from Charing Cross, which would have excluded lots of teachers working for the Inner London Education Authority. Prentice on behalf of the government stipulated that any further negotiation at the Burnham Committee on the Pay Board’s London Allowance recommendations must be on the basis of the “kitty principle”. This outcome did not satisfy the NUT. In July another half day strike and lobby of parliament was held, with the threat of more industrial action in the autumn.

The teachers’ panel of the Burnham Committee rejected the government “kitty” restriction and the NUT Action Committee prepared another referendum of London members to test the willingness to proceed.

Offer at last

At a meeting of the Burnham Committee in September, the employers’ side offered a three-tier London Allowance. This was £351 for 45,000 teachers working in the London core – all of the area in the Inner London Education Authority as well as teachers working in the six outer London boroughs of Barking, Brent, Ealing, Haringey, Merton, Newham; £261 for 36,500 teachers in the other outer London boroughs and £141 for 23,000 teachers working in fringe areas around the edge of London (this was a new area for the payment).

This offer broke the government’s “kitty principle” by £8 million. It was a huge increase in the allowance – up to 300 per cent and over 200 per cent for the main areas.

Although the NUT referendum results for action had been promising, the NUT Executive called a Special Salaries Conference for 28 September. This voted to accept this offer and the new allowances were backdated. The two-year campaign of London teachers undoubtedly also affected national salary negotiations and the size of the 1975 Houghton review award.

Can teachers and others facing a similar dilemma today learn anything from this epic struggle? Many things have changed, but where the workforce is united surely something could be learned about good tactics.