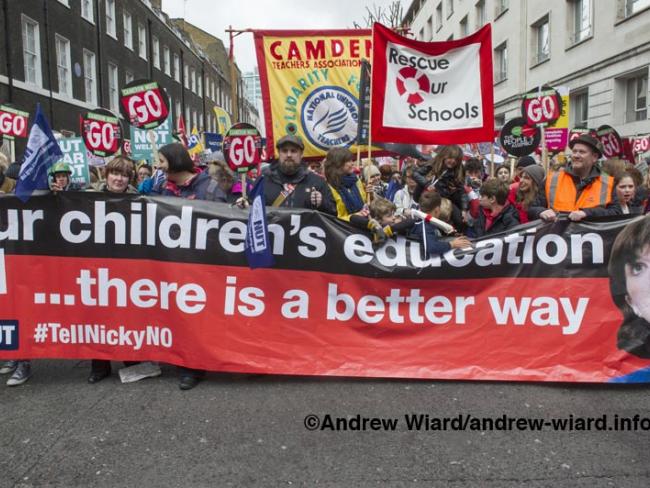

NUT banner on the 16 April People’s Assembly march in London. Photo Andrew Wiard/andrew-wiard.info

Thanks to George Osborne, ably supported by Education Secretary Nicky Morgan, a new word is gaining currency – “academisation”, the forcible conversion of schools into unaccountable academies…

Chancellor George Osborne’s announcement in the March Budget that the government plans to force all schools in England to become academies by 2022 has been met with anger and bemusement across the education world. This extreme measure was not in the 2015 Tory election manifesto – and what on earth was the government up to? Surely there had to be more to it than an obvious distraction from the abysmal Budget news about the economy.

There was. The rationale began to emerge the next day when the more detailed White Paper, “Education Excellence Everywhere”, was published, now fronted by Education Secretary Nicky Morgan. Academisation will mean staff pay, terms and conditions will cease entirely to be determined at national or local authority level. Instead, chief executives of trusts and their boards will decide.

Added to this was the plan to end university-based teacher training and do away with qualified teacher status (QTS), to be replaced by four years of on-the-job training accredited by individual head teachers.

And in case parents don’t like the way things are going, they will no longer get to elect governors for school governing bodies – called “governing boards” in the business-model academies. These will be replaced by appointed “advisory” governors with little or no decision-making powers, selected for their “correct skills mix”.

Labour first

The academy programme was introduced in England by the Labour government in 2000. The rationale was to help “failing schools” identified by the Ofsted inspection regime to be “turned around”. The idea was that Local Education Authorities (the “Education” part of the title disappeared under Labour) could not be trusted to support schools, so private sponsors from industry would be brought in to run academies instead.

Among the early sponsors were Harris Carpets and Christian evangelist car dealer Sir Peter Vardy’s Emmanuel Schools Foundation (which became associated with the teaching of creationism in science lessons). Sponsors were supposed to contribute up to £2 million capital costs to the process, although it later turned out that this requirement was quietly dropped as they became totally publicly funded. These single academy schools became grouped into what are now called Multi-Academy Trusts (MATs), under single chief executives.

The Harris Federation now runs 37 schools (with four more planned), all in London, although other MATs have schools dotted around the country. One of the central aspects of academy schools, apart from being much more generously funded than state schools, was that they would be free of the obligations of local authority schools. So in terms of curriculum, staffing (little requirement to employ qualified teachers), pay and conditions, and so on, academies were “free to innovate”.

‘There is no evidence that academies are more successful.’

They were also free from local authority oversight, allowing a number of financial scandals quickly to follow and continue now. In the most recent case, in March 2016, Perry Beeches MAT was found to have deleted records for £2.5 million of free school meals funding, and the chief executive was being by sub-contractors employed by the school – on top of his trust salary. Sir Daniel Moynahan, chief executive of the Harris academy chain, earns almost £400,000 a year.

Nearly two-thirds of secondary schools are now academies, but primary schools have proved a harder nut to crack, valuing their relationships with local community schools and councils. To date, only 2,440 of 16,766 primary schools in England have become academies. Intense persuasion has failed. Now coercion is to be used.

The government appears to have united against the move just about everyone involved in school education: unions, academics, parents, and Tory and Labour local authorities. Local authorities see the move as cutting their links with local schools created over a century ago and accountable to the electorate.

‘A full-frontal attack on teacher organisation.’

Teacher unions see it for what it is, a full-frontal attack on teacher organisation. Union recognition, common pay scales, common standards of professional qualification, decent working conditions – all would become much harder to achieve.

Even now, with is a crisis in teacher recruitment, local authority schools are finding that job adverts attract applications from significantly higher numbers of teachers fleeing from academies.

Not surprisingly, even some academy principals are worried. The immediate goal is 4,000 academy chains, with every school part of a chain. David Carter, the National Schools Commissioner in charge of academies, has talked about the creation of 1,000 new trusts. That would presumably require another 1,000 highly paid chief executives.

Once all schools and their valuable land have been handed over to the MATs, it is likely that the “edubusinesses” will become fewer and larger. Schools will lose their autonomy, governance will lose its independence and accountability, and the MATs will be free to top slice millions in public funds from school budgets.

Academic experts are questioning the educational rationale, as there is no research evidence that academies are more successful than local authority schools. The National Governors Association, usually a quietly neutral body, is angry about the emasculation of the role of school governors in general and of the input of parents in particular.

Even the head of Ofsted Michael Wilshaw, formerly head of Mossbourne Academy in Hackney, north London, recently wrote to Nicky Morgan to criticise seven large academy chains for paying their chief executives huge salaries and failing to improve educational standards.

How to fight?

It is unclear whether the changes can be introduced without the need for scrutiny by parliament, or new legislation. Teacher unions are already discussing together what to do, with the National Union of Teachers planning to ballot members for possible industrial action. Unions rightly see this move as an all-out attack on teacher organisation in the workplace.

As academies, without union rights and independent governors and with professional standards undermined, schools will be difficult places in which to organise. As always, the strength to fight this unethical onslaught against teachers and their charges will need to come from organisation at school and local authority level. Teachers have done it before. They now need to do it again.

• Related Article: Oversubscribed – and no way of coping