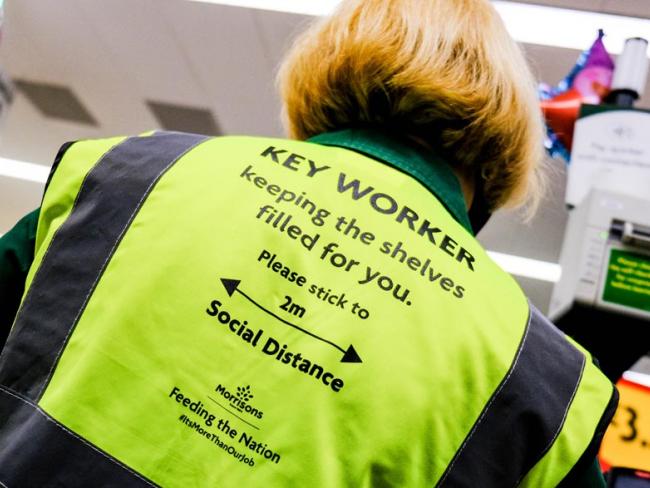

Morrisons workers have worked throughout the pandemic. Now they have private equity to contend with. Photo Richard M Lee/shutterstock.com

The stock market and the companies traded there have never been friends of workers or nations. But now they are being overtaken by something even worse – the so-called private equity companies that have become a dominant force in business takeovers…

Finance capital never stands still, and in the current century it has transformed itself. Once industry was dominated by large publicly quoted companies whose shares are traded out in the open on stock exchanges. Now the big money has retreated behind a veil, into the hands of so-called private equity.

Every month seems to bring more news of a – usually US-based – private equity company taking a stake in, bidding for or taking over a British company. And this is exactly what the government means when it talks about Global Britain – a country completely open and exposed to the whims of finance capital, wherever it comes from.

In 2016 a Downing Street spokesman described the sale of Arm Holdings to Japanese private equity giant SoftBank as “a vote of confidence in Britain”. Five years later, we have chancellor Rishi Sunak hailing the takeover of Morrisons supermarkets by a US private equity group as “a sign of confidence in the UK. It’s good news for our economy.”

It’s like farmers welcoming foxes that invade their hen coops on the basis that it shows how well the chickens are being reared.

Morrisons is the fourth largest supermarket chain in Britain, behind Tesco, Sainsbury’s and Asda. Now it is to be owned by the US private equity company Clayton, Dubilier and Rice, whose final bid topped one from a subsidiary of Japanese-based SoftBank.

Review

The bid is now subject to a review by the Competition and Markets Authority, but no one is anticipating any problems there. After all, if shareholders are happy, who can doubt the wisdom of the takeover?

Well, the 120,000 workers at Morrisons for a start. Their union, Usdaw, wants to meet the new owners to get further assurances for members there. No doubt assurances of some kind will be forthcoming, but what kind of assurances will mean anything when they come from owners whose sole interest is selling the company within a few years at a handsome profit?

‘In publicly listed companies bought by private equity the number of workers shrinks by 13 per cent in two years,’

A glance at experience in the US shows why. A study from the University of Chicago published in July this year found that when publicly listed companies are bought by private equity the number of workers shrinks by 13 per cent in two years.

Private equity deals are not about investment in these companies or their growth. They are about “maximising value” for the financial institutions and groups behind them. They suck out as much of the value as they can through dividends, raids on pensions funds or on-selling valuable parts of the business. Then they spit out the husk and liquidate what’s left.

As with most private equity takeovers, there is little clarity about how the Morrisons deal is to be financed. But for a taste of what’s possible, take a look at the takeover of Asda in October 2020.

Asda

Asda, owned by US retail giant Walmart since 1999, was sold to petrol forecourt billionaires Mohsin and Zuber Issa for £6.8 billion. To make the purchase the two Issa brothers, both born in Bradford, partnered with private equity company TDR Capital. “Great to see @asda returning to British ownership,” tweeted Sunak.

In fact, the purchase cost the Issa brothers and TDR Capital just £390 million each, barely 5 per cent of Asda’s value. And though it is based in Britain, TDR Capital is actually owned by the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority. The rest of the £6.8 billion was financed by debt and the sale of assets including petrol forecourts (to the Issa brothers) and warehouses, as demonstrated by the BBC.

“Let us hope that this is not grocery’s version of Debenhams, which was collaterally damaged by the clever financial engineering of PE, with those engineers smoking cigars still and the employees now looking for new jobs,” analyst Clive Black was quoted as saying in retail trade magazine The Grocer in February 2021.

Debenhams was bought for £600 million back in 2003 by a consortium of private equity companies which extracted £1.2 billion in dividends while loading it up with debt before selling it off by floating it again on the stock market. Weakened by the debt and expensive lease-back arrangements on its store sites, Debenhams folded last year – and 12,000 workers lost their jobs.

Scandals

That sale was nearly two decades ago, so what has changed? In one sense, nothing, because private equity companies have been doing this since capitalism began. From time to time the results are so appalling, and so public, that a scandal ensues. But nothing is done, because to capitalism asset stripping has been seen as just another way of doing business.

But the scale of private equity is now entirely different. Private equity is no longer just another way of holding shares in industry and commerce: it is the standard model.

Back in 2002, according to the World Bank, private equity and public companies were running neck-and-neck in terms of the financial worth of the assets they managed, with roughly $1 trillion each. By 2017, public companies were worth a touch over $3 trillion, but private equity’s company assets came to more than $7 trillion.

To put that into context, $7 trillion is roughly the total annual gross domestic product (GDP) of Britain, France and Italy combined.

And that’s without reckoning on the cash reserves that private equity companies have at their disposal (including bond and other holdings that can be turned into cash at short notice).

Market intelligence company Standard and Poor reported in August 2021 a global figure for these reserves – called “dry powder” in the macho language of finance capital – of more than $2 trillion. Between a fifth and a quarter of this is held by just 15 companies, mostly American.

Largely unaccountable, their tax bills lessened by complex international structures, private equity companies have become the intermediary of choice for finance capital. They are now responsible for most of the big corporate buy-outs in the world. And responsible for most of the sales, since they buy to sell.

Unaccountable

Unburdened by the pesky need to report to shareholders or gain approval for their business decisions (or the amount of money their directors pay themselves), their only mission statement is to make a quick buck.

Most importantly, they generally have much lighter requirements for reporting on their finances to government agencies. This is especially true for US-based private equity companies – and most of the world’s private equity companies are based in the US.

But it’s not just freedom from financial regulation. Unlike publicly quoted companies whose shares are traded on stock exchanges, they do not have to comply with a whole raft of regulations.

They can and mostly do circumvent many of the requirements for reporting on those irritating issues of the environment, social issues such as employment practices, and governance that companies tend to bundle together (because they are tiresome and seen as unconnected to profit) under the term ESG. Carbon emissions and COP26? No problem.

Short-termism

Workers in Britain understand the need for long-term planning, for an industrial strategy, for example, or for the NHS. But the essence of private equity investment is that it is short term. Just how dangerous that might be is illustrated by the planned sale of LV=, the mutual pensions and insurance company formerly known as Liverpool Victoria.

Even the private equity-friendly Financial Times questioned the reasoning behind LV’s wish to sell itself: “Although UK regulators have given the vote a green light, it is right to question whether private equity companies are the right kind of owners for businesses whose long-term liabilities stretch well beyond their usual horizon of ownership,” it wrote in an editorial on 29 November.

But since private equity companies typically sell on their acquisitions within less than 4.3 years it’s hard to think of any businesses whose long-term liabilities don’t stretch beyond this “horizon” – apart, that is, from private equity companies themselves. Never has finance capitalism been more reactionary than it is now, never less concerned with the long run.

Clearly, though, enough members of LV= thought the same: on 10 December a chastened board announced that the deal had failed to garner the required support. A day later the LV= chairman announced his resignation.

With the ascendancy of private equity, capitalism’s main occupation is not the creation of value in order to appropriate it and get rich. It is the opposite, the destruction of value through asset stripping in order to get rich quicker. If British workers want a future for themselves and their country, they will have to get to grips with this reality.

• This article was updated on 14 December after LV=’s members rejected the proposed takeover by private equity.