Yes, there is an economic crisis as well as the health and social crisis. But the politics of despair will get us nowhere. Instead, workers need to get to grips with the financial issues involved.

A future post-virus Britain must not go back to business as usual. Workers are already asking questions about a shortfall in industrial self-sufficiency and why there are long supply chains. We should think as well about less obvious changes – otherwise the momentum to take the opportunities offered by Brexit may evaporate.

A new outlook must prevail where working people look closely at public finance to understand how it can be applied to develop a cohesive social and economic system free from the EU.

Unravelling

The recent unravelling of financial markets says more about the frail economy before the epidemic than about the immediate impact of the epidemic itself. To that extent the financial market falls should come as no surprise. Signs of pending economic slump had been around for some time: they were being used to try to derail Brexit.

The latest indication that all was not well came from what is called an “inverted yield curve”. The last time this happened was between 2005 and 2007, just before the 2008 collapse. In early January this year it happened again.

Normally the longer the period of a large capital loan, the greater the risk and the higher the corresponding rate of interest charged by the capital lender – put that into a graph and you’ll see an upward curve. In contrast, an inverted curve refers to a graph showing the reverse of this normal interest rate relationship.

Where there is an inversion short-term capital loans become far riskier than long-term loans and attract a relatively higher rate of interest. An inverted curve is therefore a sign of much greater risk, lack of market confidence and expected volatility in the short term. It doesn’t directly cause a slump, but it is a good indicator.

‘When this happens corporate capital, with its hoarding instinct, becomes even more risk averse.’

When this happens corporate capital, with its hoarding instinct, becomes even more risk averse. This is why government finance through taxation and borrowing has a vital role to play in planning for a future.

On 7 January Britain’s Debt Management Office said it was raising government borrowing before the 31 March financial year end by £14 billion, taking the planned total to £137 billion. In other words, the government would raise £14 billion more capital over the following three months.

At the time the Office said that the fresh borrowing would support new infrastructure projects as part of becoming an independent country out of the EU. Who knows what will be left of those promises once the coronavirus crisis is over?

Previously the Office’s remit for 2019/20 was to arrange borrowing at around £123 billion. About £100 billion was earmarked to refinance some of the debt the government had incurred during the private sector banking collapse during 2008 to 2010.

A subsidy for capital

Since that collapse government debt has risen from 38 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2005 to upwards of 85 per cent now. In the main this increase represents the transfer of private sector debt to the British taxpayer: a subsidy for capitalists from working people.

The volume of debt is now set to increase further – through a further extension of quantitative easing. Early calculations suggest that the recent announcements of extra spending and public loan guarantees to help combat the economic effects of Covid-19 could rapidly lead to a further 20 per cent increase in the government’s gross debt. If those calculations turn out to be right, public debt would rise to around 110 per cent of GDP.

But that shouldn’t lead to alarmist thinking. To put things into context the debt-to-GDP ratio was 150 per cent during the First World War and went above 200 per cent during the Second World War.

The case for planning

What will be vital – as was the case in both wars – is clear, coordinated planning. Regionalism and petty separatism are hinderances. Likewise, pie-in-the-sky projections of economic needs well into the future are simply distractions. Successful planners in any field will know that the longer the projected timescales, the less likely it is that the estimated figures and expectations will materialise.

Britain doesn’t need doom mongering. It needs a five-year plan. Five-year planning with regular quarterly and annual adjustments works best.

The five-year plan approach enables economists to measure the value created by those who work. It also aids the introduction of year on year incremental improvements in production, distribution and exchange within each commercial sector. To do this requires money each year being invested in capital goods (eg new plant and machinery) rather than money printing to purchase consumption goods or used for idle financial speculation.

By adopting this balanced approach our labour productivity and with it our standard of living will improve (or should improve if workers can lay their hands on the surplus value they create). Planning in this way also helps to mitigate some of the detrimental effects of market forces and to promote economic self-sufficiency rather than global reliance.

What planning also does is squash any half-baked notion that money can be simply printed without any reference to the value generated by labour each year.

Who pays?

In the end, workers will pay for the support pledged by the government. Currently workers’ pension savings and pension funds underpin 28 per cent of the government’s total debt through being invested in government bonds (known as gilts). Banks and building societies hold a further 17 per cent of the total gilt issuance.

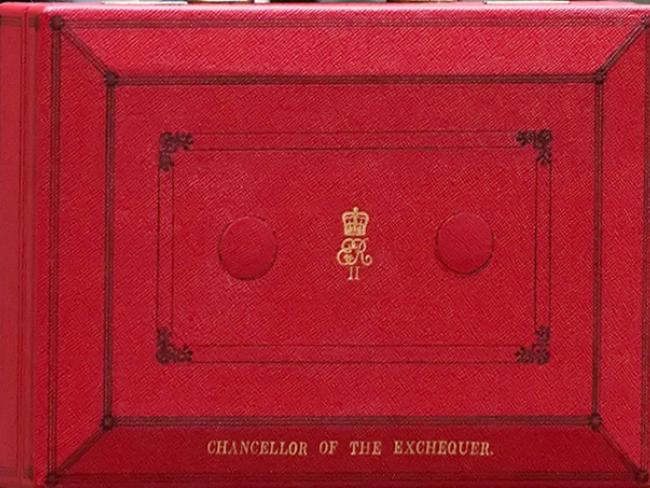

The value of some of these holdings is under threat – from a statistical trick. In the budget on 11 March (it seems a world away now) Chancellor Rishi Sunak announced proposals to change the Retail Price Index to align with the Consumer Price Index including owner occupiers’ housing costs.

The proposals are out for consultation, but we all know what government consultation means. The change is coming – and it will reduce the pension fund benefits received by millions of people.

Simply doing this would enable a wealth transfer back to the government by allowing it to write off £100 billion of current commitments. This would be achieved by downgrading what are known as UK Government Index Linked Gilts (financial instruments are held in pension funds and savings to help offset annual inflation and so help maintain the purchasing power of benefits year on year).

The various financial twists and turns of the government should come as no surprise. It is vital that people continue to engage with politics and economics in keeping with the Brexit resolve.