Leicester City parade as champions: despite their win, little has changed at the top of the Premier League. Photo RistoArnaudov/istockphoto.com

Who pays wins is the new footballing mantra – for clubs and for fans alike…

“The game is about glory,” said Bill Nicholson in 1971. The legendary Tottenham Hotspur manager was speaking to Hunter Davies during his research for The Glory Game, a meticulous examination of Spurs’ 1971-72 Division One campaign. Nicholson may have been right in 1971, but in 2016 the game is about money above all else.

How else to explain the amount of column inches, tweets, Instagram posts and more dedicated to the summer transfer window, year-on-year? Manchester United have spent some £90 million on Paul Pogba. Trevor Francis joined Nottingham Forest with the first-ever £1 million transfer fee in 1979, an amount that would have boggled Nicholson’s mind only eight years earlier.

Balance sheets

There is still glory to be had in the game, but for many football fans today “victory” has become outspending rivals, dissecting “net spends” or record sponsorship deals. Success is measured on the balance sheet, not by the trophy cabinet.

Look at the FA Cup. As recently as the late 1990s the third round weekend was the biggest event in the English football calendar. But in January 2000 the FA and Manchester United contrived that United took part in FIFA’s Club World Cup instead of defending the FA Cup as holders. Commercial interests had cemented their takeover which began in 1992 with the formation of the Premier League.

‘The League’s custodians have little interest in preserving its best qualities.’

Today the early rounds still see plum draws for the Davids against Goliaths. But now Goliath sends the kids out to fight in his place. And the final kicks off not at 15:00 but at 17:30 – to ensure higher television ratings, naturally. The glory of playing at the national stadium is cheapened by playing the semi-finals at Wembley, the sole purpose of which is to maximise FA revenues.

To add insult to injury, the replay system is under threat and moving cup matches from weekends to midweek is under serious consideration. The ultimate embodiment of the century-old meritocracy at the heart of British football has been surgically removed.

The denigration of the FA Cup is only one part of the erosion of what was once the beating heart of British football. The Football League is the envy of rival European FAs, where the lack of depth beyond top-flight competition is often pronounced. But the League’s custodians have little interest in preserving its best qualities.

Printing money

The Championship (Division One or even Division Two in old money) is the fourth biggest league in the world in terms of TV coverage; yet it is at risk of being combined with the current Under-23s Premier League, as an additional arm of the money-printing operation.

Beyond this, the Football League has attempted to spice up the Football League Trophy by inviting Premier League academy teams to compete. Most have declined; the big clubs want fewer fixtures, not more. But, as with most “modernising” initiatives, once the ball is rolling changes will be made.

The amount of money at the top of the game is monumental, but little finds its way to teams further down the pyramid, hence the attempt to bring more teams into the smaller Football League competitions. Throw in a new Premier League TV deal worth more than £2.5 billion a season over the next three years and it’s no surprise that newly relegated Newcastle United, Norwich City and Aston Villa are desperate to get back on the gravy train. The Football League television deal offers nowhere near the same levels of compensation.

Bradford City fans at Valley Parade, Bradford. But it’s money that shouts loudest now. Photo Workers

Relegated Premier League clubs receive so-called “parachute payments” for up to three seasons following demotion. The other 89 Football League clubs will divide a small percentage of the Premier League megabucks via a new contractual obligation, something the cartel of clubs at the top have previously resisted. Far from being a sign of some profound realisation that top flight football might actually need the grassroots game, this highlights the newest largesse available to Premier League clubs.

Income from the Premier League could rise to as much as £8 billion across the three years once overseas TV rights accrue. 3-4 per cent of that across Leagues One and Two seems a small price for a guarantee of keeping lower leagues compliant. Given that Sky has deals with both the Premier League and the Football League, it’s instructive that this has taken 24 years to happen.

A reliable source informed Workers that Premier League TV auctions are not the tough negotiations you might expect. Broadcasting executives simply write down the price the network is willing to pay on a folded scrap of paper and chuck it onto the table. Biggest bet wins.

Sky was blown out of the water by BT for the Champions League rights in 2013 (£897 million for three seasons, and the 2015 final was the last on terrestrial TV). Sky was determined not to be outdone again for the Premier League, without which it could lose the majority of its subscribers. In 1992 Sky paid £0.6 million for each televised match. Today’s prices see the Murdoch machine and BT Sport chucking £10.2 million a game at the Premier League.

Since the global crash in 2008 the question has been asked, time and again: How will it affect football, both in Britain and across the world? The continuing answer seems to be more money is spent by clubs, while “new markets” fill the coffers and the traditional fan base is eased out in favour of the corporate customer.

At a price

This comes at a price for workers in the broadcast media. Sky’s successful Premier League bid resulted in the media giant’s workforce being severely pared back.

While prices increase, BT Sport expands, but it is making a loss. It is using Premier League football as a vehicle to increase its broadband customer base.

The significant reduction in full-time staff at BBC and ITV has been noted by broadcasting staff union BECTU. The terrestrial broadcasters continue to haemorrhage sports rights such as Formula One and Champions League to pay per view competitors, or else having to share existing deals to make ends meet, as with this year’s Six Nations rugby.

When rights deals explode and Sky subscriptions rise, supporters inevitably suffer. This season, though, a £30 ”capped” ticket has been introduced in the Premier League for away fans following a sustained campaign by supporters’ groups for a £20 cap. Needless to say, this small concession from Premier League clubs, for whom ticket revenue is inconsequential to their overall balance sheet, was trumpeted as a win for supporters and evidence of listening to concerns. Rules dictate that this cap will mean equivalent seats in home sections are also priced at £30 per match, but this is still out of reach for many fans, given a 38 game season and associated costs.

Last season Liverpool fans forced an about-turn by the club’s US owners when they tried to increase match day prices for the new mega-stand at Anfield. That was another small success, but the purging of the working class in favour of the football tourist and the executive box continues.

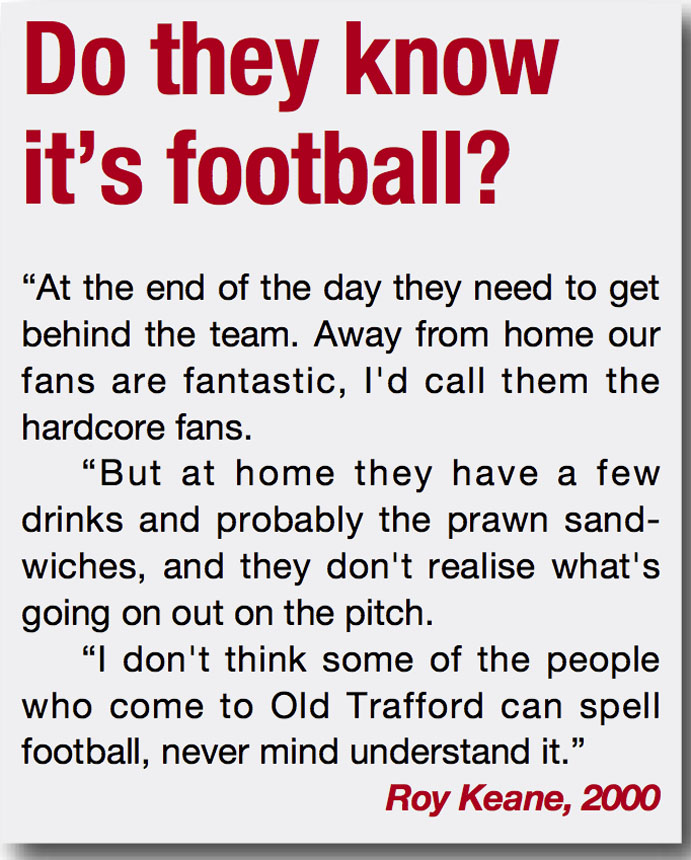

Given the size of some Premier League stadiums, 3,000 £30 tickets are insignificant when corporate box prices at Arsenal reach as much as £28,800 – for one match. When Irish international Roy Keane lambasted the “prawn sandwich brigade”, the matchday culture in Britain was already transformed in the wake of Hillsborough. But 16 years later we live in a world of Friday Night Football, Monday Night Football, never-ending football. Saturation point has long been reached but consumption continues unabated.

There might be an antidote in the current non-league revival at clubs such as Bromley FC, Dulwich Hamlet, Maidstone United, FC United of Manchester and AFC Wimbledon, the last two formed by fans of Manchester United and Wimbledon.

The United fans could no longer associate themselves with a club leveraged into debt by American hedge fund managers. Wimbledon were stolen by a small-timer from the music industry and now masquerade as MK Dons. The current fervour surrounding non-league is a positive and could be the future of the game. An afternoon at Dulwich Hamlet feels more like “real” football than the sanitised, humourless Emirates.

Sustainable?

Even non-league success may be no more sustainable than the megabucks league at the top. For every Dulwich Hamlet, there is a team in the same division watched by the stereotypical man, his dog and the Club Secretary. The current system will ultimately ensure the success stories at non-league level only become part of the establishment as they move up through the divisions.

Fan-owned clubs are held up as a positive example. But Swansea City, owned partly by a Supporters Trust, has seen its majority shareholders sell up to a US consortium. It is hard to see how much further their unique success story can develop.

‘An afternoon at Dulwich Hamlet feels more like “real” football than the sanitised, humourless Emirates.’

Despite Leicester City’s Premier League win last season, little has changed at the top. Clubs have adopted the idea that lightning cannot strike twice. Instead of smashing the status quo, the new TV deal reinforces it, enriching the haves and granting new, ill-warranted wealth to the former have-nots, who will now squander millions on agents and wages.

Today’s English top flight is essentially a global football competition that happens to be based in England. Manchester United is registered in the Cayman Islands, lines up major press releases with the opening of the Chinese Stock Exchange and has “brand partners” across the world, whether telephone cards in Malaysia or peanuts in Brazil. Liverpool, Derby, Crystal Palace, Swansea, Everton, Arsenal and more are all US-owned; cash cows for their owners.

Post-industrial Britain has seen the gradual transfer of power from the heartlands of the North West to London, as Manchester United’s rivalry with Liverpool was superseded on the field by those with Arsenal in the late 1990s and early 2000s, followed by Chelsea and now gulf state-backed Manchester City, previously an insignificance to them.

Bubble

Can the bubble burst? It has been predicted many times before and instead it swells. The game is a microcosm of the problem affecting Britain – an obsession with bringing wealth in at the expense of developing our own identity. Look at the distrust of young talented British players today, in favour of established foreign imports, compared to the past reverence for players like Duncan Edwards, Bobby Moore, Stanley Matthews and Tom Finney.

For there to be a future for football in Britain, a complete overhaul of the grassroots structure and beyond is required. The number of players at all levels and the number of professional teams is not sustainable in the long-term if money-making dominates everything. The game has been sacrificed at the altar of satellite television and is no longer a sport, but a product to be maximised, with the Premier League continuing to blow bubbles.

• Owing to an editing error, the caption to the photograph of Bradford City ground incorrectly identified the venue as Millwall's Den.