The most extraordinary march in human history changed the balance of forces not only in China but also in the world…

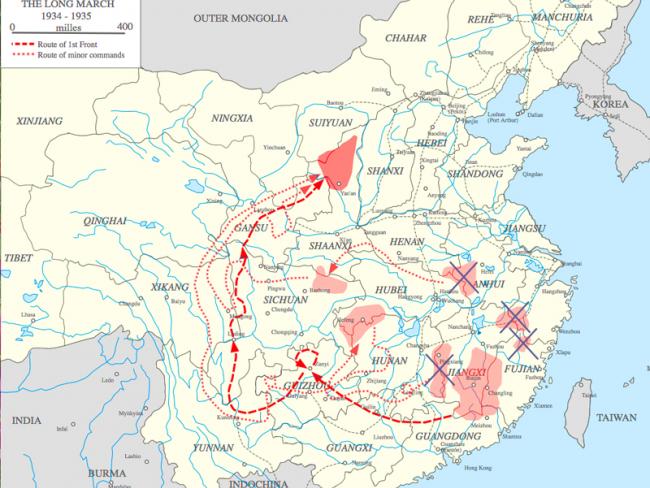

On 16 October 1934 100,000 men and women in China’s Red Army abandoned their soviet base in south-central China, bursting through the stranglehold of Chiang Kai-shek’s Kuomintang forces. This began a year-long march, a circuitous 6,000 mile trek to the other end of China. The Red Army fought nationalist armies, the troops of provincial warlords, local bandits and hostile tribesmen.

By the end of October 1935, the Red Army remnants reached Yenan [now known as Yan’an] in north China. As soon as they began their odyssey, most of the other scattered Red Army soviet bases in various parts of China collapsed, so the burden of revolutionary survival fell largely on this column.

Peasant revolts had long played a leading role in China’s history. During the 1910s and 1920s a growing number of peasants with smallholdings were turned into tenant farmers. They became subject to demands from landlords and extortionate taxation. Conditions were ripe for peasant grievances to erupt into revolt. Mao Tse Tung and other communists creatively applied Marxism-Leninism to the circumstances of China, harnessing peasant revolts to new ends. “The peasant’s fight for land is the basic feature of the anti-imperialist and anti-feudal struggle in China.”

The Kiangsi Soviet

The base in Kiangsi [Jiangxi] the Red Army abandoned had lasted nearly seven years, but by the time the march began its existence was threatened. After the failure of the Autumn Harvest Revolt in Hunan in October 1927 Mao led around 1,000 Red Army troops to Chingkangshan, a remote mountainous area. Six months later Chu Te joined them with 900 more troops.

Mao and Chu both agreed that the Red Army must subordinate itself to political direction, with some success. By 1931 the Kiangsi soviet had 200,000 soldiers and held sway over 21 counties comprising two and a half million people.

Japan invaded China in 1931; in April 1932 Mao and the Kiangsi soviet declared war on Japan, advocating a united front with the nationalist Kuomintang. The rest of the Communist Party had not yet considered taking a stance.

Kuomintang forces relentlessly attacked the Kiangsi soviet in a series of five encirclement campaigns lasting from December 1930 until 1934.Their tactics were to build trenches and concrete blockhouses as they went to create an economic blockade and to throttle the Red Army base area.

Mao lost political influence as the encirclement campaigns continued. Party members trained by the Soviet Union assumed leadership and urged a different military approach of conventional positional and defensive strategies.

Mao and Chu advocated that the Red Army should break through the ever-tightening encirclement, split into small units and fight guerrilla campaigns in the areas to the north and east of enemy lines where there were no blockhouses.

This was rejected because many thought it would undermine their credibility as a rival to the Kuomintang. But by June 1934 the soviet was reduced to just a few counties. The choice was stark: either break out or face annihilation.

Aspects of the March

On 2 October, with a sick Mao back inside the planning meeting, there was a decision to evacuate Kiangsi. A retreat began through enemy lines. A rear guard of 6,000 soldiers was left behind, enabling the main force to escape the trap.

‘The choice was stark – either break out or face annihilation.’

Marching was strenuous without regular rest and interspersed with battles. The chief scourges on the march were cholera, dysentery, influenza, malaria, tuberculosis and typhoid. The Red Army climbed snow-covered mountains and slept in the snow; at times they ate roots. During the trek the leadership adjusted military strategy and reconciled internal disputes that had at times threatened to tear them apart.

It took the Red Army 40 days to get through the blockhouses surrounding Kiangsi. Then they were attacked by the Kuomintang at Hsiang [Xiang] and lost up to 45,000 of their 87,000 soldiers. Poor strategy played its part. The fleeing army took items of no military or survival value like furniture and printing presses. These slowed them up and were soon jettisoned. The Comintern military adviser had the Red Army march in a straight line; the Kuomintang were able to predict where they would be.

A conference in January 1935 at Tsunyi [Zunyi] reinstated a mobile, guerrilla approach and passed leadership of the Red Army to Mao. Supported by Chu Te, he adopted new military tactics. The Red Army would move in an unpredictable way and was split up into smaller units making them more difficult to find in the open spaces of China.

Mao set a new target – Shensi [Shaanxi] province towards the north of China. That was a very demanding journey crossing high mountains and inhospitable grasslands that claimed hundreds of lives – all while avoiding the Kuomintang. The Red Army also contended with local warlords, who controlled much of the land in northern China.

They reached their goal of Yenan in October 1935, with 10,000 surviving soldiers – later reinforced by 60,000 others who made their way to the new base.

The Long March subtly changed in character from a desperate retreat to a prelude to victory. An unparalleled story of physical endurance, dogged grit and determination, it ensured the civil war would continue. It also enabled the Red Army to survive and grow, eventually to lead the ejection of the Japanese occupiers and then defeat the Kuomintang. Setbacks to the revolution in China since 1979 do not in any way diminish the significance of this amazing feat.

• A fuller version of this article is available as The Long March (1934-35)