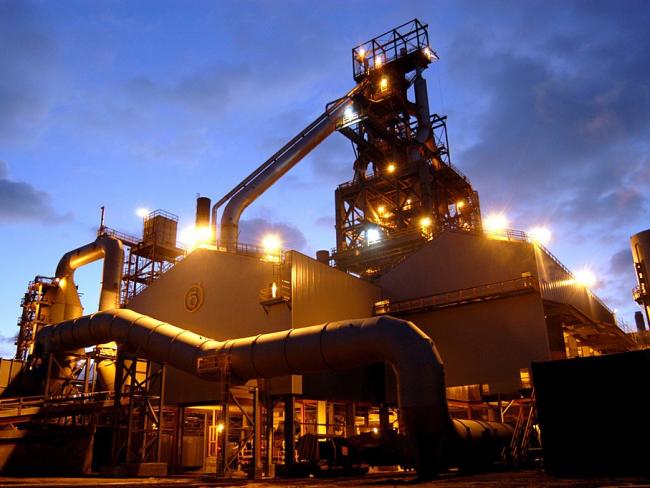

Blast Furnace Number 5 at Port Talbot, South Wales. Photo Grubb/Wikipedia.

With tariff wars looming, Britain needs to look to its own industrial needs for steel…

World raw steel production capacity far exceeds current demand. That’s the background against which the USA has imposed tariffs on imported steel. But Britain has quite different interests from the EU in responding to that development.

Most of the increase in steel production capacity since 2000 has been in China, which is currently responsible for around half of world production (see related feature box Too much of a good thing?). The result has been a flood of underpriced steel and closures in producing countries.

Members of the G20, comprising the largest industrialised and developing nations, agreed a deal in November 2017 intended to address the implications for their home industries. This mainly focused on China. The EU is the largest open market for steel in the world, so is vulnerable to increased imports in response to tariffs elsewhere.

The USA imposed 25 per cent import tariffs on steel imports this March (and also a lower tariff on aluminium). This may undermine the 2017 agreement, but is not a straightforward response to that or necessarily directed solely at China.

Temporary exemption was granted to the EU and others. Brazil is the second highest exporter to the US, providing 13 per cent of its imports. But like South Korea, Australia and Argentina, it has now been permanently exempted from the tariff.

Tariffs were imposed on imports from the EU from 1 June. They also applied to Canada (responsible for 16 per cent of imports) and Mexico (9 per cent) after both declined to agree to changes in the NAFTA trade agreement with the US.

Trade imbalance

Britain exports around 350,000 tons of steel a year to the US. That’s less than 7 per cent of our total annual production, and worth around £350 million. This is mostly made up of specialised products, not currently available from US steelmakers. EU exports to the US, on the other hand, are valued at around £6 billion a year and comprise an inventory that US steelmakers could easily replicate.

There are also signs that imports into the EU from Turkey, which is subject to US tariffs, are increasing. These are competing with German and other steel producers in the EU, but generally not with British products.

The response of steel unions (GMB, Unite and Community) to the US tariffs rightly attributed problems in the industry to overcapacity, but ignored the role of the EU and the opportunities that Brexit offers to make our own trade deals.

‘Steel unions have ignored the role of the EU and the opportunities that Brexit offers.’

Britain needs to look to its own industrial needs for steel as well as to the future for our production. Import controls for the basic raw material, rebar, used as precursor for specialist steel production required in all aspects of engineering and construction, is a positive step forward but one that needs to be extended. Most of Britain’s imports come from EU member states, Germany in particular.

Britain’s current annual output is around 10 million tonnes. Germany produces at least three times that amount and benefits from generous state subsidies, particularly cheap electric power. Poland, France, Italy and Sweden have capacity in excess of our own.

Specialist

Britain has a continuing requirement for mass production of the basic steel rebar from imported coal and iron ore. This capacity needs to be protected and developed. But although Britain is a small player in raw steel production, we are a world leader when it comes to specialist steels and associated research.

The government is promoting its industrial strategy and may be starting to confront the issues for Britain’s steel industry. Working in collaboration with Liberty House headed up by the entrepreneur Sanjeev Gupta, it has published the “Greensteel” strategy. This aims to drastically slash the amount of raw material imported into Britain. To make that a reality, it proposes to dramatically increase our capacity to re-cycle scrap using electric arc technology powered by renewable energy.

Such a programme would have only a tenth of the carbon footprint generated by the use of blast furnaces. Around 6.6 million tons of raw steel are currently imported into Britain each year. But out of the 10 million tonnes of scrap steel created annually, a staggering 7.2 million tonnes is exported for processing. The amount of scrap steel is projected to double over the next 10 years.

Investment

Liberty House aims to capitalise on this by increasing its steel recycling capacity fivefold to 5 million tonnes a year through an investment programme costing around a billion pounds and creating hundreds of jobs. The mothballed steel plant at Newport has been reopened as has a big furnace at Rotherham. And a number of other assets have been acquired, mainly from the Tata conglomerate.

‘We are a world leader when it comes to specialist steels and associated research.’

The nuclear industry, electric car development, HS2, the Northern Powerhouse and the house building programme will all require access to specialist steels. Scrap steel can be re-used by exploitation of technologies developed here in Britain.

Outside the EU our steelmakers will be the preferred supplier for this extensive programme of works, being able to compete on quality, price and delivery through local supply-chain networks and with no legal obligation to tender with direct competitors.

It’s even possible for steel produced in Britain to be exported to China. British Steel was formed out of the former Tata long steel (bars and wires) division and posted a profit for its first year of operation 2016-2017. It has secured a deal to supply crane rails for the Yangshan deep water facility in Shanghai. That’s part of a £57 billion project to build the world’s largest cargo port in Shanghai.

These rails are a high quality specialised product made at the Scunthorpe works and rolled at the plant in Skinningrove, Teesside. The company is also supplying other similar developments in China and aims to pick up further contracts elsewhere in Asia as a result.