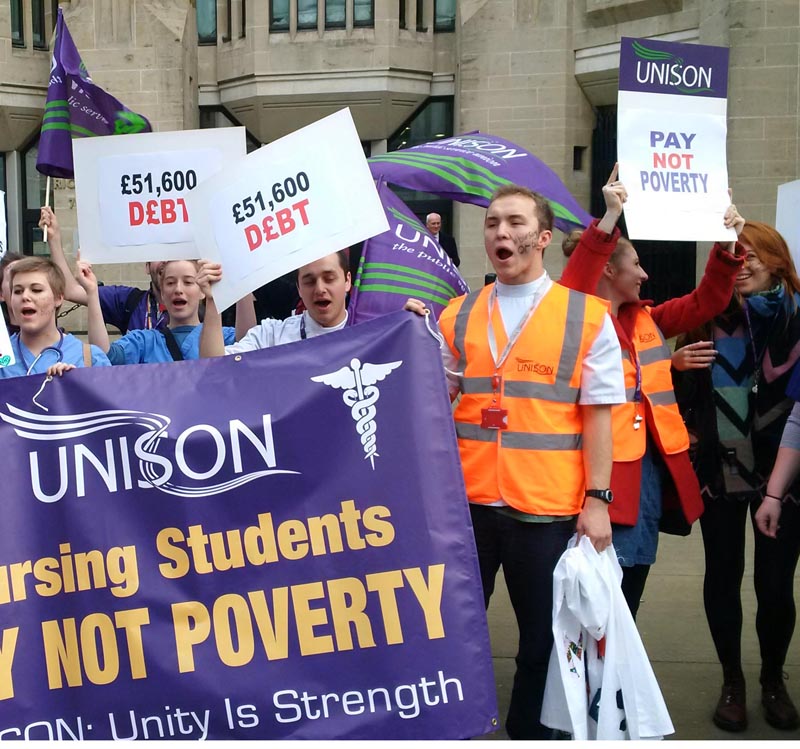

2 December 2015: Midwifery and nursing students demonstrate outside the Department of Health in Whitehall, London. Photo: Workers

How can Britain be short of nurses and midwives and yet cut back on training places and support? The answer is simple: like the imperialists they are, the government plans to rob other countries by importing their trained specialists…

There are many ways to attack a profession but the most effective is to attack the new recruits coming into the ranks. First there was Jeremy Hunt’s attack on junior doctors. Then the government spending review in November 2015 claimed to be “spending more money” on the NHS when it actually contained a proposal to remove £1.2 billion each year.

Health Education England, an “arm’s length” body of the Department of Health currently provides £1.2 billion for the tuition fees and bursaries of nursing, midwifery and other Allied Health Professionals (AHPs) such as physiotherapists. The government proposes that from September 2017 all such health students would have to apply for a loan to cover tuition fees and maintenance. Those graduating in 2020 face projected debts of £51,600.

Nazi propaganda used the maxim that if you tell a lie big enough and often enough, people will come to believe it (coined by Hitler, often attributed to Goebbels). In this case it is three big ones.

Lie 1. The ‘new money’

Firstly, a huge slice of the supposed “new money” for the NHS mentioned in the review is a direct transfer from the pockets of future health care students or their parents to the Treasury.

It is estimated that those students or their families will be repaying the debt for over 30 years. Given the addition of interest payments, this is a most uneconomic way of funding an essential workforce.

Lie 2. ‘Treated just like other students’

The second big lie is that nurses, midwives and AHPs will be pleased to be “treated just like other students”. Just one problem: they are not like other students. Their academic year is much longer with the combination of placement hours and study weeks, and these are in the workplace. Take nursing: the number of hours in the workplace is specified by the nursing regulator, the Nursing and Midwifery Council. They spend over 2,300 hours in the workplace during the typical three-year programme.

In order to learn, students are expected to be working under supervision and thus the spending review proposal means they would be taking on the massive debt and working the typical 12-hour shifts for no pay. The constraints of their programme mean they do not have the opportunity other students may have to undertake part time work.

Lie 3. That it would lead to an expansion of training

The third and the biggest lie of all is that this imposition of tuition fees and attack on the bursary will lead to more student nurses, midwives and AHPs joining the professions. The government points out that currently there are more applicants than funded places. It argues that universities would be “free” to expand the number of training places available. That completely ignores the deterrent effect of large debts on the individual student. The average age of student nurses is 29 years; they would be taking on a debt lasting the whole of their working life.

‘The third and the biggest lie of all is that fees and the attack on the bursary will lead to more students.’

The government also ignores that hundreds of health students undertake their qualification after graduating in another area and, under its own rules, cannot access the student loans system again. In any event, they could not contemplate a second loan!

Universities are entirely reliant on the NHS and other health services to provide those practical training placements and nursing staff with the additional qualification to assess students. But these resources are already in short supply and overstretched. Indeed under the new proposals, maybe the universities will have to pay the NHS and others for these placements. Where would the madness end?

Fighting back

Within days of the announcement student nurses and midwives were on the streets protesting. Indeed on 2 December as parliament was debating the bombing of Syria, less than 100 yards up Whitehall student nurses and midwives were standing outside the Department of Health in a loud and lively protest against the plans. Then on 8 December they joined other students on the national demonstration about the cost of education. The message from students is very clear: “I would not have been able to join this profession if these proposals were in place.”

The other sentiment which captures the mood of the student body, the wider profession and the public is that “this is just wrong”. It’s summed up by the statement on the Royal College of Midwives website: “Debt upon debt upon debt. And all so you can join the NHS, help the country and help drive down that midwife shortage. It doesn’t seem right that someone who will spend a lifetime caring for women and delivering NHS care should have to pay tens of thousands of pounds just to do so. It’s just wrong.”

The proposal is subject to a period of consultation. A parliamentary petition is due to be presented on 11 January and a further public demonstration is planned. The students are busy coordinating their action via a Facebook page. They show the same energy and humour seen in the junior doctors’ campaigning tactics.

This fight impacts on all health professions and demands a wider response. It affects nursing, midwifery, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech and language therapy, podiatry, radiography, dietetics, orthoptics, operating department practice and prosthetics. It may also affect paramedic courses. It also involves the health educators of all those professions, typically members of the University and College Union (UCU), which is opposed to tuition fees. The need for all these forces to combine has never been more urgent.

One place where support will not be forthcoming is from the university employers. For some years they have been aggrieved that the funding for health courses (a transfer of taxpayers’ money from one government department to another) has not been meeting the costs. So they have welcomed charging fees as an improved alternative. They have even pointed out to prospective students that loans will give them more “cash in hand” than a bursary!

The current proposals have not arrived out of the blue. They are part of a cynical and much wider plan for Britain to avoid

taking responsibility for its own workforce planning in the NHS. This continues a long pattern of immoral poaching of qualified staff whose training has been funded at the expense of their country of origin.

In the current period where it is common to hear voices raised that all migration is a “good thing”, the alternative view that migration is theft of skill from other countries must be heard.

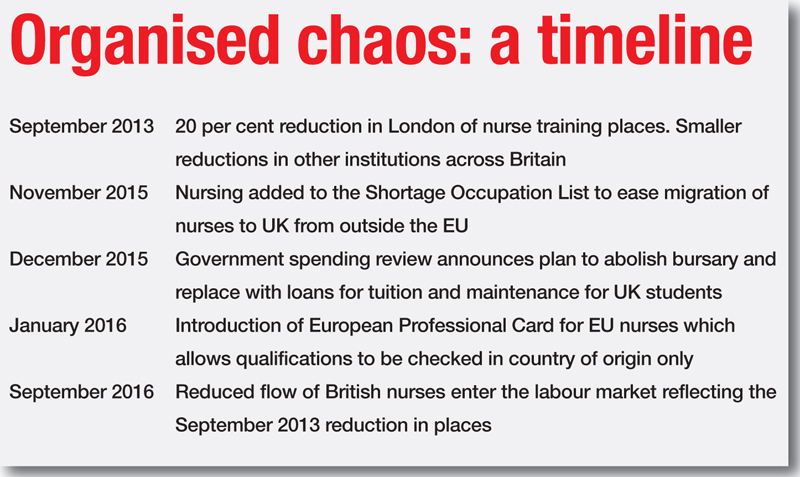

The avoidance of workforce planning in the NHS has a long history and has led to periods of restricted training opportunities followed by limited expansion when the need was dire. The current circumstances are more acute as the period of contraction has not been followed by any expansion.

In Britain the government-backed Centre for Workforce Intelligence predicts the NHS will be short of at least 47,500 nurses by 2016. The most recent period of sharp contraction followed the election of the coalition government in 2010 which saw the Department of Health agree to significant reductions in numbers in training.

In London with its sharply rising population this led to a decision to reduce the September 2013 intake by 20 per cent. In fact the University of West London lost its contract to offer any nursing programmes in that contract round.

The lunacy of the proposal was highlighted by all the nursing unions. The UCU opposed it too, also having to fight redundancies of nursing lecturers as a result of the proposal. Originally there were plans for further reduction in 2014 and 2015 but these did not proceed, so a small victory. However, the acute position predicted for 2016 is a direct result of the decision to reduce places three years ago.

Poach from outside the EU

The shortage of nurses is part of a world-wide shortage as documented by the World Health Organization. For example the health ministry of India has recently identified that they have a shortage of 2.4 million nurses. This has not stopped Theresa May in November 2015 agreeing to place nurses on the “shortage occupation list”, thus easing the immigration rules and allowing employers to recruit (at great expense) outside of the European Economic Area. See Box, right, for the impact on India, for example.

Adding nursing to the list in the month before announcing the changes to UK nursing education in the spending review was probably a deliberate ploy to dampen NHS employers’ reaction to the proposal.

Poach from EU countries

Recent years have seen a steady flow of EU nurses joining the UK nursing register. The impact on other European countries has been marked. In 2015 the Spanish Council of Nursing president Dr Máximo Jurado complained about British recruitment agencies, telling BBC News: “They lie – they fool nurses.” Likewise the vice-president of Portugal’s nursing regulator, Dr Bruno Gomes, has complained about British recruitment in his country.

The National Nursing Research Unit at King’s College London has highlighted that this overseas workforce is very unstable, with many returning home following NHS expenditure on their recruitment, orientation and induction. Yet the trend is set to continue and intensify with a new EU initiative.

From January 2016, a new “European professional card” will be introduced for many health professionals. This means Britain will be reliant on regulators in other European countries to make sure those coming to work here have the correct documents and qualifications. The card will apply initially to nurses, pharmacists, and physiotherapists and it is planned to apply to doctors from 2018.

This initiative has not received significant press coverage and unlike in the medical profession there has been no opposition to this move by the UK nursing regulator, the Nursing and Midwifery Council. The medical profession has a two-year period to oppose the initiative. And the country as a whole might have the option of the referendum to leave the EU before this applies to doctors.

Niall Dickson, Chief Executive of the General Medical Council, speaking about the European professional card, said “…there are major weaknesses in the regulatory system and it must be right that every country in the EU should be able to check that doctors coming to work within their borders have the competency, skills and cultural understanding to treat its patients safely. We believe that the introduction of the European professional card for doctors would further jeopardise our ability to protect patients in the UK.”

The fight for the bursary for health care students cannot shy away from the wider context of the immoral and, as of January 2016, largely unregulated use of overseas staff. There is no shortage of British applicants for British health profession programmes – they are all oversubscribed. The real shortage lies in the absence of a government willing to produce a workforce for one of the country’s essential services.

• Related article: India's loss