6 June 2023

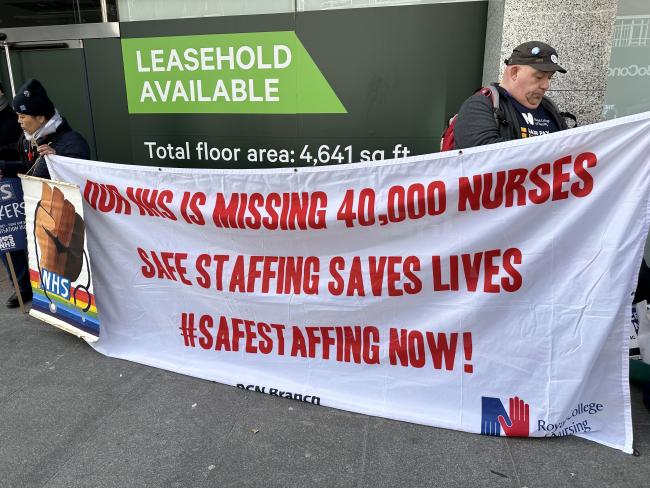

RCN banner on SOS NHS demo, London March 2023. Photo Workers.

The “great nursing brain drain” is a worldwide concern. Importing nurses from other countries is no answer to NHS staff shortages, no matter how attractive it might seem. Instead, improved retention of nurses already working would be a step in the right direction.

And there’s a detrimental effect on the countries supplying nurses. Many of them report that nurses their state has paid to train are recruited by a richer country, damaging their own healthcare services. That’s the reality of migration.

Safeguards

The World Health Organisation reported on the worldwide shortage of nurses even before the pandemic, and sought safeguards against recruiting nurses from poorer nations. The WHO has again raised this issue.

The WHO code of practice included a “red list” of countries with the most pressing need for healthcare professionals and which should not be targeted for recruitment. But it’s permitted to accept people who apply “of their own accord”.

Poaching

As Howard Catton from the International Council of Nurses (ICN) recently highlighted, a small number of countries, including Britain, are responsible for this poaching. The code of practice allows for the government to reach a bilateral agreement with another country – as it did last year with Nepal, a red list country.

“Recruitment is from countries which can ill-afford to lose nurses.”

Catton said to the BBC on 6 June that “We have intense recruitment taking place mainly driven by six or seven high-income countries but with recruitment from countries which are some of the weakest and most vulnerable which can ill-afford to lose their nurses.”

He also described this as a situation which is “currently out of control” and highlighted the example of 1,200 Ghanaian nurses joining the UK register in 2022. Many of them are among the most experienced nurses; the loss to the health care system is far greater than the head count suggests. Ghana is also on the WHO red list.

Loss of experience

Nursing around the world relies on learning in practice to train the next generation. That can’t happen effectively where vital experience is lost. It takes a generation to replace, and only then if the poaching stops.

Last year the number of midwives, nurses and nursing associates registered with the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) to practise in the UK grew to a record total of 788,638. That's about 1.2 per cent of the estimated UK population.

These include 27,142 new professionals educated in the UK and 25,006 professionals educated around the world. The number of people leaving the professions fell slightly last year to just under 27,000. Overseas recruitment was a significant driver of the gross increase – and the level of UK-based training is only enough to replace the current number of leavers.

Retention fears

There are concerns about future retention of staff and that the numbers leaving the nursing professions will increase. Just over half those who left the register last year said they did so earlier than planned. Almost a quarter reported leaving much earlier than they’d expected. And most said they were unlikely to return to the professions, including younger leavers.

‘Effective measures to retain staff could reduce overseas recruitment.’

The important information for nurses and their employers is that effective measures to retain staff could reduce overseas recruitment by 50 per cent.

The NMC commented when reporting these figures on 31 May, “Our leavers’ survey found five compounding workplace factors that frequently influenced people’s decisions to leave: burnout or exhaustion; lack of support from colleagues; concerns about the quality of people’s care; workload; and staffing levels”.

Pay

In the midst of a national pay dispute which saw many nurses taking industrial action for the first time it may be surprising that the question of pay did not feature among the top reasons for leaving the register. But the survey shows that pay was cited more often by younger leavers – 1 in 4 of those under age 55.

The survey included “lack of support from colleagues” for the first time, but it’s ambiguous. It implies a colleague reluctant to help another, but it is often an inevitable consequence of low staffing levels. And the five headline reasons reported for leaving have much in common with the experiences driving the pay campaign and strike action.