Work in progress at the new reactor site at Hinkley Point, Somerset. Photo EDF.

Independence from the EU will usher in a new era of opportunity for Britain. What do we want for our country? This demands debate wherever people work, interact or socialise – and an essential topic is energy production…

Energy is an essential of modern life, without which there would be neither heat nor light nor the power to run machines. If we are to be truly self-reliant, our energy supply should be reliable, affordable, safe and clean.

Reliable:

The present electrical energy generation mix in Britain includes fossil fuels, renewables and nuclear. We are not overly reliant on one source, but the picture is constantly changing. Coal is disappearing. And although natural gas still supplies 40 per cent of our electricity, less than half comes from the declining North Sea and Irish Sea fields. The rest is imported through pipelines from Europe or as liquefied natural gas from around the world.

The use of renewable sources is becoming more assured, particularly with developments in the offshore wind turbine industry. The government has moved away from rewarding wealthy landowners to site inefficient wind turbines in some of our most beautiful and remote locations. However, the long term effects of offshore wind turbines on marine life is still unknown.

Britain is a world leader in the technology and construction of offshore wind power. The government is investing jointly with science and industry to bring down the costs of this emerging energy source. For example a £7.6 million research programme was launched last year partnering the Universities of Sheffield, Durham and Hull with industry leaders Siemens and Dong Energy.

Wind and solar power are by nature intermittent. That’s a big drawback because we need power day in, day out. Biomass (burning wood pellets or other plant material) can’t replace fossil fuels in the long term. Supply is limited; it takes time for trees to grow and most biomass is imported, notably from the USA at present.

Nuclear generation compares favourably with gas and other fossil fuels on availability, known as the “capacity factor”. Nuclear plants are typically available at full load over 90 per cent of the time, although those in Britain have been at around 75 per cent recently. In contrast gas-fired stations have a factor of just over 30 per cent.

Because of the capacity factor, we would need two or three times the nominal generating capacity relying on gas rather than nuclear power. Yet development of nuclear power in this country has languished for decades because of political hostility and indifference.

There are 15 nuclear power stations operational in Britain, producing on average over 20 per cent of our electricity. One of them, Sizewell B, is expected to continue for another 17 years. Two, at Dungeness, have a lifespan of around 10 years. The rest without exception will cease generating within 5 years.

Ten sites were identified in 2010 for new nuclear reactors, later reduced to eight. The only one where construction has begun is Hinkley Point in Somerset, where two French-owned reactors are planned to come on stream in 2025. This is perverse, given that nuclear power is the only significant form of generation currently available that doesn’t either create CO2 or rely on intermittent sun or wind.

Affordable:

We are assailed daily with claim and counterclaim about the price of electricity from different sources. The cost of production is less for wind power when the wind blows, as it is for solar power when the sun shines. But it’s not as simple as that, because the price paid by households and businesses depends on the energy market, subsidies and taxes, all influenced by government.

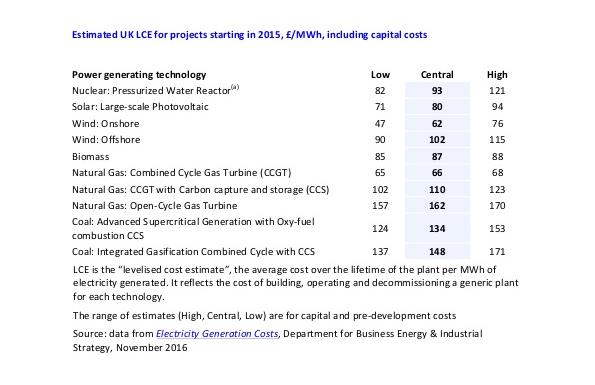

The government carried out a detailed comparison of the total whole-life cost of each generating technology in 2016. The table left summarises some of the key figures. Coal is the most expensive. Once solar and wind power are discounted as unreliable for continuous supply, nuclear, natural gas and biomass emerge as the only serious options on grounds of cost.

Gas and biomass have to be continuously imported in high volume. Such limitations do not apply to the radioactive material needed to run a nuclear power station. The conclusion is that nuclear offers the best prospect of continuously affordable energy, supplemented by modern gas turbines.

Cost estimates for nuclear depend on assumptions about capital spending. But those costs can reduce as more nuclear plants are built – as long as the government plans to do so.

The guaranteed strike price set for Hinkley Point was widely questioned as it was double the market price of electricity at the time. But that price was influenced by government policy and can’t be used to compare costs for the future.

Safe:

The World Health Organization and others carried out a study in 2010 into the safety of different forms of power generation. Coal was least safe; that’s to be expected given the air pollution it causes and the number of workers involved in its extraction worldwide, often in conditions no British miner would tolerate.

Surprisingly, though, nuclear was found to be the safest, 40 per cent better than wind! But there is a widely held perception that nuclear power is a disaster waiting to happen, based on three notable incidents; Three Mile Island in the US in 1979, Chernobyl (now in Ukraine) in 1986 and Fukushima (Japan) in 2011.

It’s worth looking at the facts. There have been no detectable deaths due to radiation from the meltdowns at either Three Mile Island or Fukushima. In the Japanese case about 1,000 people died in the panic and chaos of a precautionary evacuation. And around 16,000 died as a result of the earthquake and tsunami which led to the reactor meltdown.

‘Huge strides in nuclear safety and efficiency have been made.’

The explosion at Chernobyl in 1986 was far more serious, releasing between 5 and 10 times as much radioactive material as Fukushima. Two workers were killed outright and 28 died of acute radiation sickness within weeks. Since then 19 further deaths have been directly attributed to the accident. A UN report in 2005 estimated that 4,000 premature cancer deaths may occur over 80 years as a result of contamination from Chernobyl.

The British nuclear industry is required to operate in a much safer way than prevailed at Chernobyl and that must continue to be rigorously enforced. But disposal of nuclear waste remains a valid concern. Research will be needed into technological solutions for the long-term disposal of existing and future waste.

Clean:

We want our power generation to be as clean as possible. Nuclear power scores highly as a clean energy source, as even its detractors are forced to admit.

Unlike fossil fuels and biomass, nuclear energy produces no carbon while generating electricity. Carbon is produced during the construction, mining and decommissioning stages of a power station’s life; that’s true for all sources of energy, whether “clean” or not.

Power for Britain

Nuclear power should be the principal source of energy in Britain because it is affordable, reliable, safe (within the provisos outlined above) and clean. It should be the chief component of our energy generation mix, alongside gas and renewables.

Huge strides in nuclear safety and efficiency have been made in recent years. And there are also innovative designs such as the modular model (see Workers May/June 2018). The future doesn’t have to be like the past, but it does have to be planned for.

There are grounds for optimism. Britain was at the forefront of the development of nuclear power. We still have repositories of skill and research such as the Dalton Institute at the University of Manchester.

Earlier this year the National College for Nuclear opened a “Southern Hub” to promote the skills needed in the building and operation of Hinkley Point C. Its Northern Hub, based near Sellafield in Cumbria, will play a role in planned developments there. But these innovations are piecemeal and need to be strengthened.

There are still those who argue that so-called green energy is the future, by which they mean renewables. The National Infrastructure Committee, set up by George Osborne, recently called on the government to plan for 50 per cent renewable energy by 2030 and to halt any further nuclear expansion. But planning on this basis is utterly illusory. It is important that we speak up for the place of nuclear in our energy plan. Let’s have science in place of prejudice!