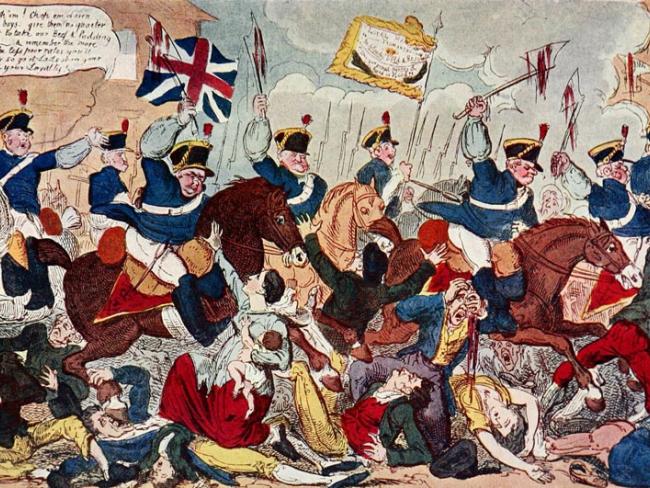

George Cruickshank’s famous cartoon of the massacre. The speech text reads: “Down with ‘em! Chop em down my brave boys: give them no quarter they want to take our Beef & Pudding from us! ---- & remember the more you kill the less poor rates you'll have to pay so go at it Lads show your courage & your Loyalty.”

Two hundred years ago, 18 people were killed and hundreds injured taking part in a peaceful rally calling for the reform of a corrupt parliament…

On 16 August 1819 80,000 men, women and children – peaceful and unarmed demonstrators – converged for a meeting in the centre of Manchester. Walking in impressive contingents from surrounding towns and villages they gathered on open land in St. Peter’s Field.

Throughout industrial Lancashire, a combination of clever organisation and widespread publicity had combined to produce the biggest demonstration ever seen in the country. Some contemporary newspapers claimed there were far more than 80,000 people present.

Yet, just after the start time of 1pm, the local magistrates sent in soldiers from the 15th Hussars together with volunteer cavalry from the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry to arrest the main speaker Henry Hunt and disperse the demonstration.

Imprisoned

The event was immediately labelled the “Peterloo” Massacre by James Wroe, a journalist at the Manchester Observer newspaper, in punning reference to the battle of Waterloo four years earlier. The name has deservedly stuck. Wroe was himself imprisoned for a year and his newspaper closed down by the authorities in retaliation.

The meeting at St Peter’s Field was called in support of “the most speedy and effectual mode of obtaining Radical reform in the Commons House of Parliament”. This demonstration was a Lancashire rally, not just a Manchester one. After a long period of economic hardship and political suppression the working class had many grievances; no wonder the meeting was well supported.

Plans were made. Each surrounding village was given a time and place to meet, from which its members would proceed to bigger towns before all were to coalesce in Manchester behind numerous bands and self-designed banners.

Alarm

Before the rally, the government established “A Committee in Aid of the Civil Powers”, which considerably heightened alarm. Previously the government had alerted Yeomanry Corps around the country, including the cavalry of the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry.

There had been a two-year build-up of hostility between the yeomanry and the populace. Quietly, prior to Peterloo, they had sent their sabres to be sharpened. Also, a proclamation in the Prince Regent’s name condemned, though did not ban, seditious assemblies and the practice of drilling. A few days before the St. Peter’s Field meeting Henry Hunt, the principal speaker and prominent radical, checked with the local magistrates that it was legal and could go ahead. They told him it could.

The demonstrators brought “no other weapon but that of a self-approving conscience”. As the crowds reached central Manchester, they were in good humour. Once they were packed inside St. Peter’s Field, Hunt arrived and mounted the platform. He was known as “The Orator” for his stirring speeches at mass meetings.

Yeomanry sent in

Immediately the magistrates ordered Manchester’s corrupt and much feared deputy constable to arrest him. To help him they sent in the yeomanry, who clattered into the crowd and arrested Hunt who was physically abused as he was led away. The magistrates now sent in the 15th Hussars too. The crowd fled trying to avoid the flashing blades and horses’ hooves.

‘It took a century and more for the ruling class of our country to concede some aspects of parliamentary reform…’

Within 20 minutes the field was empty save for bodies and the discarded debris of the rally. The troops rallied in front of the magistrates’ building and gave three cheers. Later the Prince Regent sent a message commending their “preservation of the public tranquillity”. The chief magistrate William Hulton wrote to the Home Secretary Lord Sidmouth praising “the extreme forbearance of the military”.

Peterloo was the scene of the worst violence ever to occur at a political meeting in Britain. 18 died and at least 654 people required medical treatment. A quarter of the casualties were women. Afterwards the magistrates claimed they had read the Riot Act, the formal procedure necessary to order the dispersal of a crowd, but no one heard them. And they certainly did not allow the statutory hour for the gathering to leave. Hunt was sentenced to two-and-half years’ imprisonment for “seditious assembly”.

Despite the loss of life and subsequent protests, Peterloo did not immediately affect the way parliament was run. Towards the close of 1819, a further and more drastic set of repressive measures was passed called the Six Acts which (1) equipped the magistrates with more drastic powers in dealing with offenders, (2) prohibited drilling and the use of arms, (3) strengthened the laws against blasphemous and seditious libel, (4) gave the magistrates the power to search private houses, and to confiscate weapons, (5) restricted still further the right to hold a public meeting, and (6) subjected the periodical pamphlets published by the radicals to the newspaper tax, with the object of preventing cheap publications.

Suffrage

It took a century and more for the ruling class of our country to very gradually and very reluctantly extend the suffrage and concede some aspects of parliamentary reform through acts in 1832, 1867, 1884, 1918 and 1928. Generations of rulers were probably surprised at their ability to preserve the dominance of capital and to contain the potential of working people during this journey, even with universal suffrage.

We are still discovering today in the battle raging for Brexit and independence, how we must defeat the rotten corruption in the parliamentary edifice that still strives to hem us in. We are still learning from the past experience.