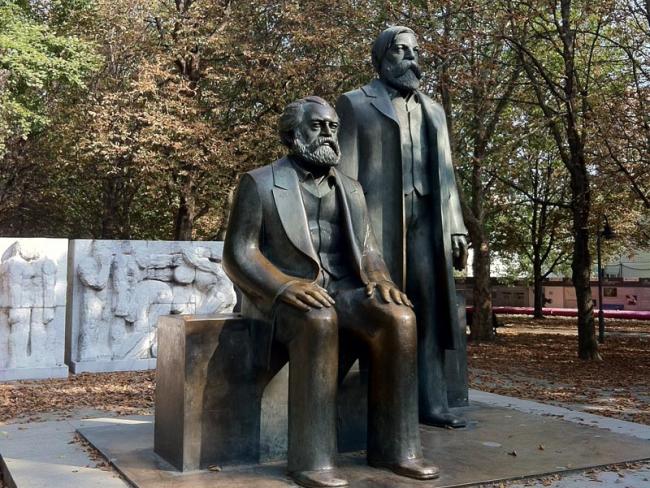

Statue of Friedrich Engels (right) with Karl Marx, Berlin. Photo Workers.

Born 200 years ago, Friedrich Engels played a great part in the working class movement in the 19th century, particularly in Britain…

Friedrich Engels was born on 28 November 1820 in Barmen, a growing industrial town in Germany’s Rhineland. Europe was recovering from the Napoleonic wars and about to enter a long period of political and economic change.

Engels, whose contributions are not always fully recognised, played a full role as a writer and political leader until his death in 1895. By the end of his life modern industrialisation had spread from north west Europe across the world.

In that time capitalism had matured into an international system, recognisable today. The working class grew as capitalism expanded, developing both its organisation and thinking to inspire the revolutions of the twentieth century.

Engels moved to Manchester in 1842, working for two years in his father’s textile firm, which had a mill there. He had already written articles critical of German society and had begun to think of himself as a socialist. But in Manchester, Engels transformed his view of the world.

Crisis

Britain had just been through a great economic crisis. There were strikes against wage cuts and agitation for working class political representation through the People’s Charter. But the capitalist class had reasserted itself in a brutal way. Chartist leaders were arrested; the movement never regained its momentum. Wages were not improved, but trade unions began to reorganise in new ways.

Engels explored Manchester, the centre of British industry, and other industrial towns. He talked to workers, debated with trade unionists and wrote for socialist publications. He read all he could and studied the state of the working class.

From this experience Engels wrote The Condition of the Working Class in England, published in German 1845. And although it was not translated into English for over 40 years, the conclusions he drew influenced later political activity and thinking – his own and that of many others, including Karl Marx.

Other writers had described the raw, desperate struggle for survival in the early years of capitalism – Britain was the first country to experience this. But unlike Engels they were visitors; they viewed the appalling working conditions and poverty as the fault of workers or a necessary evil to be moderated where possible.

In contrast Engels took his observations and asked himself why things were that way. He did not ascribe this to the evil intent of individual capitalists but saw that it was a product of that economic system. He foresaw that other countries would experience the same path – Germany, France, USA and so on.

Engels dealt with workers as a class and looked beyond pauperism. Henry Mayhew wrote London Labour and the London Poor a few years later, describing similar conditions. But that lacks an analysis or understanding of the working class; it is of interest only as a vision of its time.

Unemployment

In contrast Engels takes his detailed, systemic survey and analyses the political and economic developments that created what he saw. He was probably the first to identify and articulate the need of capitalism to have a “reserve army” of the unemployed to create competition between workers and to keep wages down. That’s a commonplace idea now, but was radical then.

Engels describes how workers defended themselves and how their experiences drove them towards organisation and acting as a class with the same economic position in society and the same economic interests. Also a radical view.

The concept of a class with a common interest leads to the idea that workers have their fate in their own hands and need not rely on others, even well intentioned liberals. At the time in Britain those liberals were arguing for abolition of the Corn Laws and for free trade. But workers understood that for the most part their motivation was not altruism but to reduce costs for manufacturing capitalists – that is, wages.

‘Engels examined the economic laws driving capitalism and its cycles of boom and bust…’

Engels also used his studies to examine the economic laws driving capitalism and its cycles of boom and bust. Yet the idea that capitalism can be modified to eliminate unemployment and crises still persists 150 years later in the thinking of too many workers. It’s worth going back to what Engels wrote, not to be horrified by the conditions described, but to gain a better understanding of how capitalism worked then and now.

In 1844 Engels met Karl Marx, with whom he had already started to correspond. Over the next three years Engels was engaged in developing his political thinking and practical activities among German workers in Brussels and Paris.

This led Engels and Marx to set out the main principles of the socialism they had worked out in the Communist Manifesto, first published in 1848. It emphasised that “the struggle of the proletariat with the bourgeoisie is at first a national struggle. The proletariat of each country must, of course, first of all settle accounts with its own bourgeoisie.”

Marx and Engels saw the working class as thinking beings who can wage and win the struggle for socialism. They always stressed that “The emancipation of the workers must be the act of the working class itself.”

After the defeat of the 1848 revolution in Germany, Marx settled in London. Engels became a clerk again back in Manchester in 1850. They maintained a lively exchange of ideas, corresponding almost daily until Engels joined Marx in London in 1870.

In London Engels took part in working class political activity again. Over many years he contributed to and edited Capital, Marx’s key work on political economy, and wrote works of his own about socialism and society. But his early experience in Manchester was the foundation on which he built his work.