10 March 2024

Doctors lobbying the Conservative Party conference, Manchester, October 2023. Photo Workers.

People find it hard to get an appointment with their GP within a reasonable time. One reason is that we are short of doctors.

The latest figures from NHS England released on 7 March show that the delays to GP appointments are getting longer, not shorter. The impact is significant – delayed diagnosis of serious conditions in the worst cases, unnecessary anxiety in others.

Pressure

Beyond that, appointment delays increase pressure on A&E and hospitals generally as people bypass primary care. And doctors point out they can’t just work longer hours and see more patients as they are already close to the limit.

According to analysis published by the BMA in February, England has 2.9 doctors per thousand people. In comparison the figure for Germany is 4.3, and the average for the 38 industrially-developed OECD countries is 3.7. This is 2021 data, the most recent available.

Delays

In January 2024, NHS figures show that out of the 32 million appointments booked with GPs in England, 5 million (over 16 per cent) were more than 14 days after the appointment was made. And a further 4 million (nearly 12 per cent) were between 8 and 14 days after booking.

This situation is worsening. In January 2023 14.5 per cent of appointments took place more than 14 days after booking; the year before, the figure was 11.9 per cent. The figures for 8 to 14 days have risen too, but not so markedly – 11.5 per cent in 2023, 10.3 per cent in 2022.

Vacancies

There are currently 8,858 vacancies in England for doctors in primary care and hospitals. Yet the government refuses to train enough young people to fill these vacancies. This problem has worsened since the coronavirus epidemic, but predates it.

The BMA reports that since 2015 the NHS has lost the full time equivalent of 1,830 fully qualified GPs. In January 2024, there were just over 37,000 fully qualified GPs working for NHS England, amounting to the equivalent of 27,534 full time posts.

‘The government pledged to double places at medical school, but it’s not happening.’

Last June, the government pledged to double the number of funded places at medical school from 7,500 to 15,000 by 2031. But like so many such announcements, it’s not happening.

A report in the Guardian on 25 February based on a leaked letter suggested that government will only fund 350 additional places for trainee doctors in 2025-26. That’s less than a quarter of the number our medical schools had been told to plan for. And at that rate it would take over 20 years to reach the 15,000 target.

Worthless

The letter included a promise of greater numbers in later years, but subject to review and funding – a worthless commitment. It takes around 10 years to train as a GP. Medical schools can’t turn training on and off at short notice. Nor can NHS workforce planning work like that.

Government action amounts to an abandonment of any rational approach to ensuring there are enough doctors to meet Britain’s needs. It pays lip service at times to the correct idea that we cannot – and should not – rely on doctors trained abroad; but in reality it has no other plan.

Safe working

Doctors have pressed for the creation of wating lists for GP appointments. In the view of the BMA, this means setting safe working limits on the number of appointments each GP can carry out in a day.

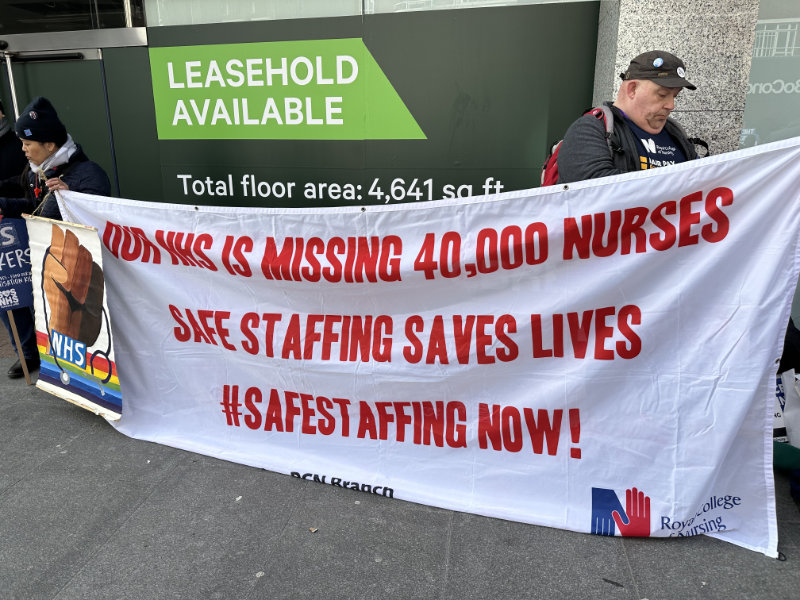

That restriction can protect doctors and the quality of primary care in the short term. But it can do nothing about rising patient to staff ratios. And while more patients could be seen by nurse practitioners or community pharmacists, those professionals are in short supply too.

Local initiatives sponsored by NHS England have helped GP practices to deal with particular problems. But for the most part these are aimed at improving quality, and can’t be the answer to a shortage of doctors and other health care staff.