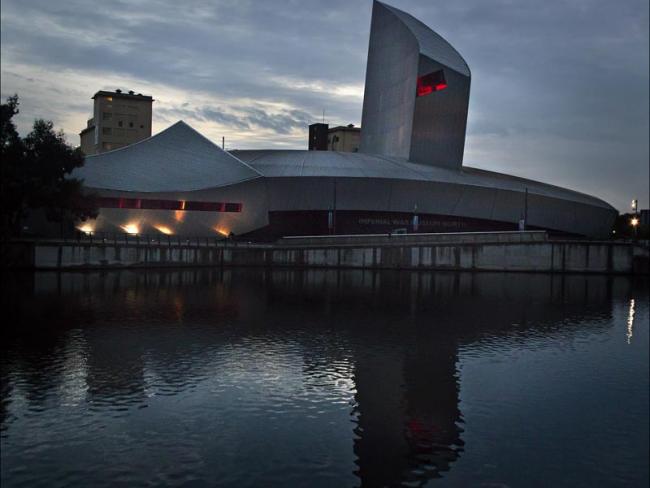

An exhibition at the Imperial War Museum North, in Manchester, gathers thought-provoking oral recollections from across the political divide…

An exhibition at the Imperial War Museum North in Manchester explores how many incidents of the Troubles in northern Ireland, 1969 to 1998, remain highly contested. Called “Living with Troubles’, it shows that many people who lived through them have very different perspectives on what happened.

The exhibition graphically illustrates the damage wrought and lives destroyed when a working class allows itself to be divided on sectarian lines, when we lose sight of ourselves as a class and of what unites us.

The focus is on four themes with relevant images, video, objects and – most importantly – contributions from people who lived through them. The museum has gathered oral recollections from people across the political divide – and those that tried to straddle the divide. Visitors can listen to or read the oral contributions and should find them thought provoking.

The first of the four themes is titled “The night of the 27-28 June 1970”. The agreed facts are that violence erupted on that night at the junction of the republican Short Strand district and loyalist Newtownards Road and three people died, two Protestants and one Catholic.

Visitors to the exhibition can listen to two men who were children on that night and caught up on the edges of the violence. They lived a short distance apart yet their memories of what happened, with the loss of those three lives, are very different.

One, at the age of 16, saw men with guns (neighbours that he knew) go down the street to defend the local Catholic church and his community from attack by rioters. The other man was 15 at the time and is adamant that there was no gun battle, no guns from the Protestant side, but that gunmen shot and killed two peaceful Protestant marchers and one Catholic.

Contradictory

An explanation board from the exhibition’s curator team states that this event and the contradictory recollections of it epitomise the divisions of the near 30 years of conflict in northern Ireland, but that encouraging people to express their different versions of events allows peace to endure.

“The Descent into Violence” covers the rise of paramilitary groups – the split of the Irish Republican Army into the Official IRA and the Provisional IRA, and the emergence of the Red Hand Commando, the Ulster Volunteer Force and the Ulster Defence Army. It has contributions from ex-members of those groups, from the British Army, the police and fire services, and from civilians. Civilians made up more than half of all those killed during the conflict.

Two particularly pertinent contributions come from Liam McAnoy an ex-Official IRA member and Beano Niblock an ex-Red Hand Commando member.

Discrimination

Liam McAnoy: “But the reality was that discrimination wasn’t solely against Catholics … in actual fact working class Protestants were discriminated against because it worked on the basis of nepotism: in other words if your father worked in those industries you were more likely to get a job. So quite a lot of working class Protestants who had no relationship to engineering, to the shipyards were also discriminated against.”

‘A graphic illustration of the damage wrought and lives destroyed when a working class allows itself to be divided along sectarian lines…’

Beano Niblock: “It was only when I went into prison…these guys although they are born on the other side of the road, although they’re from a different religion, there’s where the commonality is you know? Because we’re working class and if you look at the statistics the vast majority of people who went through the prison system would have been working class; the vast majority of people who were killed in the Troubles were working class; and it’s not a coincidence you know? So there has to be that connection between the communities here, although I didn’t see that growing up, probably because I was tutored not to see it.”

“Hell in a Wee Place” does an excellent job of contrasting life in northern Ireland during the Troubles with the rest of the UK. Photographs show that the towns and cities of northern Ireland had the same shops and road signs, but someone going to work might find a soldier in their garden, British army checkpoints on one road and a paramilitary checkpoint on another.

Shopping in the city centre meant going through a turnstile, being frisked and a bag search. Bombs and shootings were commonplace and public information posters warned children not to pick up items in the street. The oral contributors talk about how all this was “their normal”.

The final theme, “Today and the Future” is weaker, perhaps not surprisingly as it speculates on what might develop. But there are still interesting contributions.

For example, Jim Gibney, who spoke about the night of 27-28 June when he was 16, is now a Sinn Fein member. He says, “Armed struggle is not some sort of immutable principle…it’s not employed when it’s not required…in the absence of armed struggle the political momentum you generate around a party like Sinn Fein…working with others, the SDLP, the Irish Government, the US…that you create a momentum where peace has taken root and on the back of that change is possible.”

The exhibition closes on 29 September but some of the photographs and videos used, and other material about the Troubles, will continue to be available online at www.iwm.org.uk.

• The CPBML opposed the sending of troops to northern Ireland from the outset in 1969. We remain committed to respect for the Irish people’s right to national independence and self-determination. Read our 1974 pamphlet, Ireland One Nation, online.