25 August 2021

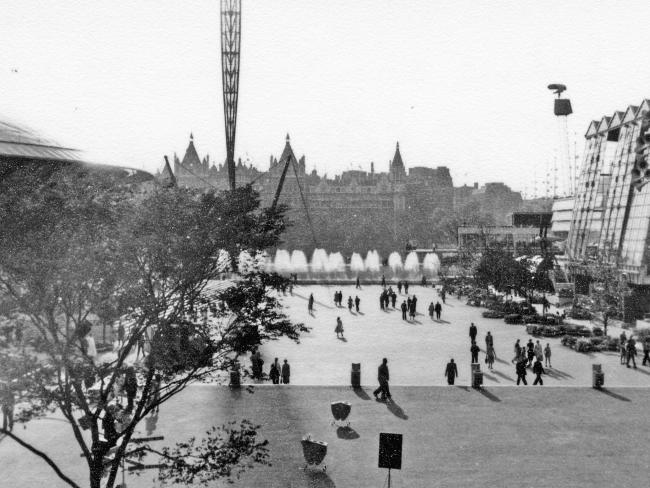

The Festival of Britain site with the iconic dome (left) and Skylon (centre). Photo Ben Brooksbank/geograph.org.uk (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Seventy years ago, in the midst of post-war austerity and rationing, Britain found the will to create a remarkable, popular festival…

Post-war Britainwas beset by problems. For the majority of people, life was hard and difficult. The daily routine was still making do on very little. The euphoria of victory in Europe had long since given way to a more humdrum existence.

The 1951 Festival of Britain was an antidote, looking to the future. It was quite unusual, with a strange mix to its events, but it was immensely enjoyed and appreciated by those who attended. Eight and a half million people were to visit the South Bank Festival out of a population of around 50 million.

Proposed in 1943 by the Royal Society of Arts, the idea of a festival initially attracted much opposition and antagonism. The RSA, a body where designers, artists and industrialists met, suggested to the wartime government that an international exhibition to take place in 1951 on the centenary of the 1851 exhibition.

Initially little happened, even after the end of the war. British people faced many difficulties. Essentials were in short supply – butter, meat, tea, sugar and coal were all rationed. Clothes only came off rationing in 1949. 20 million Britons lived in homes without baths and hot water, while nearly a fifth of London’s homes were officially classed as slums. All that was made worse by the winter of 1946-47, the harshest on record.

And in 1947 the Labour government introduced national conscription for two years for all men aged 18 to 26 because an immense amount of military manpower was wasted hanging on to a doomed empire. That added to the frustration of lengthy demobilisation that had lasted into 1946. Britain in 1950 spent 6.6 per cent of its gross domestic product on defence, far more than other countries.

Strong

Though post-war Britain was passing up many commercial opportunities, the country still had a strong manufacturing base, as the festival exhibits were to demonstrate. British technological innovation matched that of the USA in developing radar, computers, telecommunications, television, aircraft and jet engines. Britain built more ships than any other country and was the leading European producer of coal, steel, cars and textiles. In the south, science-based light industries were beginning to make an impact.

In late 1947 the government decided to go ahead. It set up a Festival Council with a broad yet specific brief for “…a national display illustrating the British contribution to civilisation, past, present and future in the arts, science and technology and in industrial design”.

The earlier idea of an international exhibition was abandoned and there would be no coverage of empire or commonwealth. Once the brief was set, politicians played little role in planning or development, whilst politics was kept at a distance. For instance, there was no reference to topics like nationalisation or the NHS. The festival was to have a focus on Britain and to be all about Britishness, though in practice it proved difficult to reach a consensus of what that meant.

Faith

Gerald Barry, a journalist and past editor of the News Chronicle, headed the planning. He was a firm believer in putting the modernist architect at the centre of post-war reconstruction and had a faith in economic and social planning. The Council had leading cultural figures on board, many of them young.

At first the five members of the Festival Executive Committee were daunted and at a loss where to start, overawed by the staggering nature of the brief. They began by studying in detail the 1851 Festival, which sparked ideas and set free their confidence. Barry employed a large number of talented, young people, mostly unknown to the wider world. They were left free to develop their ideas – and had slightly under three years before the curtain was due to rise on their efforts.

They set about putting on a show with broad popular appeal that would leave a lasting impact on the public imagination, all arranged inside a tight budget. The festival was expected to meld education, inspiration and pleasure and to expose fresh ideas to a wide audience. It would give commerce and the arts in Britain a chance to show what they could do.

Tonic

In the words of Barry, it was to be “a tonic to the nation”, celebrating Britain’s recovery from the war and a demonstration that Britain had within itself the talent, imagination and energy to create a new society.

The aim was to create new works of art and new social amenities for the people; give the younger architects, artists and designers a chance to prove their talent; launch a spectacle of futuristic designs; see modern technology in action, and leave behind some permanent contributions to the future.

In short the festival aimed to be a lesson in national identity, to provide a reason for citizens to be proud and give an image of the future. The planners had to counter initial pessimism and scepticism that this could be a success.

They insisted that the festival must be enjoyable and fun, adorned with bright colours, a cultural reawakening after years of drab uniformity. It was an assertion that, having won the war, the British people were not about to lose the peace.

‘It was an assertion that, having won the war, the British people were not about to lose the peace…’

The selected site lay between County Hall and Waterloo Bridge on the south bank of the Thames. It was soggy and derelict, but centrally placed with good communication links, close to iconic London landmarks. Work began immediately on a wall to protect the area from flooding.

And as a bonus the London County Council (using its own funding) had already given the go-ahead for a new concert hall to be opened there in 1951 – the Royal Festival Hall. In tune with the ethos of the festival, it incorporated many modern features.

Memorable

The planners set about creating a commercial and cultural showcase of Britain. For the promotion of trade. For the enlightenment of people. For making a display spectacle of the mechanical wonders of the age. Soon there were 100 architects and display designers drawing and experimenting for five crazily exciting months, devising interesting and memorable things to fit into the 27 acre site.

A slender steel and aluminium structure in the shape of an outsized exclamation mark – Britain’s first high-tech piece of architecture – was selected to represent the festival after an open competition. Named the Skylon, it was a distinctive and image rising 90 metres in the air.

It served no purpose whatsoever, except to make people stop, stare and wonder. Seemingly freestanding and defying gravity, high-tension cables slung between three steel beams held it in place. Lit from inside, at night it could be seen all over London.

Bold

The festival’s icon was the pancake-shaped Dome of Discovery. With bold, clean lines, light and space, it combined practicality and beauty to house and display the best of British invention and enterprise.

The Dome was 110 metres in diameter with a smooth metal cover of aluminium alloy, a material not often used for substantial buildings at that time. The ribs underneath were supported by a steel box ring girder, itself held 12 metres above ground by a series of slender lattice steel masts. To many children familiar with futuristic space comics, it looked pleasingly like a flying saucer.

Over 10,000 products of British enterprise were judged worthy of display – ranging in size from locomotives to lipsticks and in value from many thousands of pounds to a few pennies. In 1951 washing machines, water heaters, fridges, vacuum cleaners and electric irons were beyond the experience of well over half the population.

'With bold, clean lines, light and space, the Dome combined practicality and beauty...'

Pavilions dedicated to land, agriculture, mining and industry, surrounded the Dome, telling the story of Britain. The exhibitions included: A History of Telescopes; a Polar Theatre; Alice through the Looking Glass; Power and Production; Sea and Ships; Transport, Agricultural and Country (with live creatures!) and many more.

Elsewhere the themes were much more people orientated – arts and crafts, education, depictions of the “British at Home”, their recreations and more ambitiously and, trickier, their character. The river front was given a seaside makeover – a promenade, deckchairs, ice cream stalls and, optimistically, sunshades.

Dotty

The Lion and the Unicorn pavilion, whilst probably promoting an artificial national self-image, was simply dotty and became one of the most popular festival features. Its odd name was supposed to represent two opposing facets of the British character – the stolid, unimaginative Lion and the highly individualized, eccentric, unpredictable Unicorn. A public appeal for models made of unlikely materials or machines built for unpredictable purposes resulted in a delightful, bizarre collection of exhibits.

Overall the small site was planned so as to give a sense of space and allow for easy, leisurely movement between the pavilions. This feel was achieved by a series of connecting patios, each of contrasting shapes and colours, with new points of interest to catch the eye at every turn. There was an imaginative use of glass giving a transparency to buildings

Poplar housing

More space was required, in particular to show what could be achieved with socially motivated architecture. A site was selected in Poplar, a deprived area that suffered extensive war damage, to create a purpose-built, lower living-density environment for 1,500 residents in a village-like community.

The Lansbury Estate, as it became, had its own schools and church, an old people’s home, a pedestrian shopping centre, covered market place, pubs and open spaces. It should have had a medical centre too but NHS funds ran out.

Also, a new wing was built at the Science Museum in South Kensington. Its opening exhibition, timed to coincide with the festival, explored the scope of the scientific revolution. Its narrative was composed by Dr Jacob Bronowski and pushed him into the limelight nationally. It received 1,500 visitors a day.

The festival reached beyond London with well-attended exhibitions across Britain, including Industrial Power in Glasgow’s Kelvin Hall, and the Ulster Farm and Factory exhibition outside Belfast. There were two touring exhibitions, one on land and the other on the Festival ship, Campania, a converted aircraft carrier.

In 1949 local authority leaders were summoned to hear about the festival. They were sent away to organize festival events in their own areas and turn it into the party of the century. A programme of events from the sublime to the ridiculous were organized in almost every part of the country. There were for example 23 funded arts festivals across the country and 1,600 towns and cities uplifted and improved some aspect of their daily amenities to mark the festival.

Fun

Also in London but still close to the river, land was acquired for the Battersea Fun Fair and Pleasure Gardens. It was integral to the festival, yet totally devoted to one aim, fun. Sponsorship was solicited from commercial organisations: for example Guinness paid for a huge clock that went mad each quarter hour; and Sharp’s Toffee presented a Punch and Judy show. The Worshipful Company of Brewers threw in three beer gardens.

The Emett miniature railway, owing more to Heath Robinson than George Stephenson, proved a showstopper, recovering its entire cost in three weeks. Another attraction was a Mississippi showboat complete with a whirling paddle wheel, smoke belching from tall tunnels and the music of Old Kentucky on a barrel organ.

The largest single pole tent ever erected held performances night after night by music hall stars of the day. The Fun Fair offered a Big Dipper and other attractions. And Battersea’s pride and joy was the Grand Vista, the setting for popular twice-weekly fireworks.

Passenger boats ran an ever crowded shuttle service between the two main Festival venues. Over eight million people visited and paid to enjoy the Battersea Pleasure Gardens, matching the numbers for the main site.

On time

Festival organisers had to overcome many obstacles, not least petty government bureaucracy and the shortage of building materials, then subject to strict regulation. But the Festival opened on time despite an extremely wet winter and spring in the preceding months.

After the Festival ended, the site was cleared. Most of the buildings were demolished except for the Festival Hall. The new government didn’t want the exhibition site to become permanent. The Skylon and The Dome went to scrap. Lots of festival items were sold off at public auction. But the Pleasure Gardens in Battersea – the overtly fun bit – remained open.

As with many other big festival projects, it is difficult to say exactly what benefits the 1951 Festival brought to the British people, though as an entertainment project it was generally felt to be an amazing success.

Certainly Britain did not really go on to actively maintain or extend its industrial, technological or scientific prowess in succeeding decades. However, attitudes to modern design and materials were probably changed significantly. And without doubt the Festival did encourage more Britons to want to experience events beyond the normal.