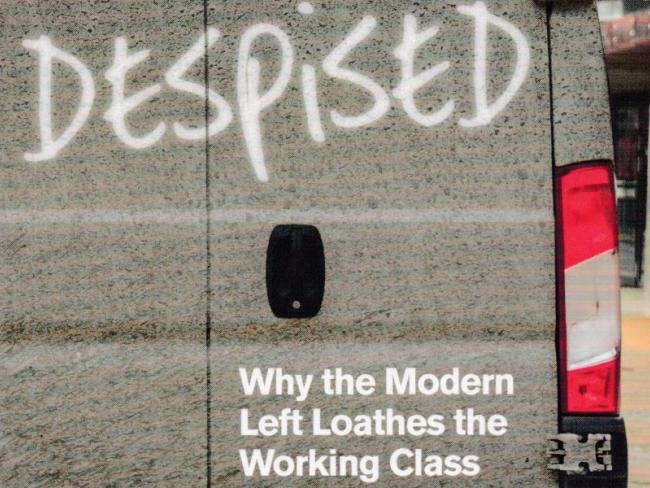

Despised: why the modern left loathes the working class, by Paul Embery, paperback, 216 pages, ISBN 978-1509539994, Polity, 2020, £16.92. Kindle and eBook editions available.

This useful and interesting book by Paul Embery analyses and criticises the anti-working class attitudes of all too many in the labour movement.

Embery is a firefighter and trade unionist from Dagenham in east London. He observes, “we are social and parochial beings with a profound attachment to place and a desire to belong. …working class people seek to revive the politics of belonging, place and community as an antidote to galloping globalisation and rapid demographic change.”

Opposite

Many people in the Labour Party claimed that the vote for Trump and the vote for Brexit were both parts of some worldwide reactionary movement. One key difference demolished this claim. In the US election, the richer you were, the more likely you were to vote for Trump. The opposite applied in the EU referendum.

A 2016 report by the Centre for Social Justice and Legatum Institute titled 48:52: Healing a divided Britain found that “At every level of earning, there is a direct correlation between household income and your likelihood to vote for leaving the EU – 62 per cent of those with income of less than £20,000 voted to leave, but that percentage falls in steady increments until, by an income of £60,000, that percentage was just 35 per cent.” The richer you were, the more likely you were to vote to stay in the EU.

It also seems that the better off you are, the more likely you are to be a Labour party member. A 2017 survey found that 77 per cent of Labour party members were higher earners. And nearly half its members lived in London and southern England, and 57 per cent were graduates.

Immigration

Embery tackles the issue of immigration head on. He asserts that “…to argue that mass immigration had depressed wages, which it had, was not to blame immigrants personally for that outcome – any more than to argue that unemployment holds down wages, which it does, is to blame the unemployed. It is to make a simple statement of fact.”

As the Irish Congress of Trade Unions said in 2006 in a submission to the Irish government proposed labour market reforms: “It is an iron law of economics that an abundant supply of labour pushes down its cost. It is insulting people’s intelligence to pretend otherwise.”

Andrew Neather, a speechwriter for Blair, wrote in 2009, “the deliberate policy of ministers from late 2000…was to open up the UK to mass immigration.” That Blair imposed this policy of open borders is no surprise; it is perfectly in line with his globalist politics.

Jeremy Corbyn also espoused this policy. The Labour Party now has significant problems in even discussing the issue post Brexit. Clearly a policy of free movement leads inevitably to the domination of global capital.

‘A policy of free movement leads to the domination of capital.’

US presidential candidate Bernie Sanders pointed out in 2015 that a policy of open borders was “a Koch brothers’ proposal. That’s a right-wing proposal that says, essentially, ‘There is no United States.’ … it would make everybody in America poorer. You’re doing away with the concept of the nation state.”

Embery also campaigned energetically to leave the EU, paying the price for his activity in being disbarred by his union from his elected officer post. He argues that Leave represented the chance for change but Remain was the conservative choice. As he argues, “Socialism before Brexit is impossible. It must be the other way round.”

He decries the divisive politics of promoting minority and individual interests, and the sneering elitist attitudes towards traditional views, with which, as he observes, the Labour Party is now infected from top to bottom. Witness the sheer vindictive nastiness all too often expressed, for example, on the website of the Guardian where posts denounce the ‘idiotic electorate’ (yes, all of us apparently, even Labour voters!) as ‘gammon’, ‘knuckle-dragging’ and so on.

National identity

Splitting the working class is never good for us, benefiting only the employing class. For all too many in the Labour Party, all identities are fine – except apparently one that matters greatly to so many people – national identity.

The labour movement should indeed ditch what Embery calls the “destructive creeds of identity politics and state-sponsored multiculturalism” because they actively promote separateness and division. But this statement is undercut by his proposal to create a separate parliament for England!

All these Labour policies and attitudes helped to produce the 2019 general election result, when the Conservatives won the votes of 48 per cent of lower earners, and Labour won 33 per cent. The Labour Party had made itself irrelevant.

Embery joined the Labour Party aged 19, and has been a committed member ever since. In spite of this book’s sense of despair throughout at what the party has become, his final chapter asserts that it should change into something completely different, the age-old reformist fallacy. The reader might feel that he does so without much conviction. We would still be in the EU, indeed we would still be in the British Empire, if we had all taken that attitude.

Politics is not all about making Labour electable, or about defeating the Tories. The country needs the policies and attitudes that Embery urges in order to rebuild as an independent, united nation.