Welding robots on an automotive industry production line. Photo Praphham Jampala/shutterstock.com.

A union plan called Manufacturing Matters has been launched. With Covid-19 and Brexit, we not only desperately need a plan for a manufacturing-based recovery – we also have the opportunity to implement it…

Amid the catalogue of job loss announcements in the past month or so – from Rolls-Royce and British Airways to numerous retailers – it is clear that the Britain will see significant reduction in value creation from the manufacturing sector caused by the Covid-19 pandemic.

The Covid-19 crisis has not stopped discussion about the future of British industry. In fact, in many ways it has made the discussion even more relevant, and even more intense. But is there a current UK industrial strategy fitted to meeting the current industrial challenge?

While some manufacturing employers such a Rolls-Royce have reacted by slashing staff and investment, unions have been spurred on to press the need for a strong manufacturing base. It’s a welcome change from endless broadsides – largely ignored by their own members – against Brexit. In fact, the concentration on industry has opened the eyes of many to the advantages of an independent Britain free from the EU.

Under the campaigning banner of Manufacturing Matters, Unite Assistant General Secretary Steve Turner has placed before the union’s membership a plan to recover and rebuild our manufacturing base. It deserves wider circulation and discussion throughout the trade union movement.

The plan – launched in November 2019 – implicitly rejects EU state aid legislation by calling on the government and the devolved administrations to be “brave” by investing now, using equity stakes and public procurement as strategic tools, and bringing forward public projects to meet unions’ wider social policy objectives.

This plan has also been presented to government at recent meetings. It puts the case that any strategy for the economy to recover from the impact of Covid-19 must put British manufacturing at its heart.

Unite is calling for the government to take the lead by intervening directly to provide support for Britain’s “manufacturing capabilities, capacity and resilience as we reposition our economy to address the challenges ahead”. That includes not just rebuilding manufacturing, but expanding it.

World class

The truth is that the service sector cannot survive and thrive without a sound manufacturing base. Unite’s plan recognises that Britain can only afford the NHS and other public services if it has a “world class, high value, exporting manufacturing sector”.

But that won’t happen on its own. As Unite recognises, only through a coordinated industrial strategy can Britain meet the union’s objective of “levelling up our economy; protecting and enhancing jobs, upskilling our workforce, offering apprenticeships to coming generations, supporting our families and defending communities in a just transition of our economy”.

‘Unite is calling for the government to take the lead by investing directly…’

A link to the climate lobby is also made by the reference to the need for the “million plus green jobs” that can be created to meet wider social policy and climate change commitments. But that requires a recovery plan with manufacturing at its core, as well as “ensuring that we manufacture the products we need here in the UK, while training and deploying an army of installers and maintainers”.

Unite repeats its call for “direct, strategic state intervention” as the way of meeting the challenges of Covid-19, Brexit and climate change head-on. And, the union says, success will require the state’s “genuine collaboration” with industry and trade unions as well as with government at all levels.

Young people have been hit hard by the Covid-19 crisis, but they are going to have to be the people to drive the recovery of manufacturing into the coming decades. Manufacturing Matters addresses this in its last section – which it might have been more appropriate to place at the beginning of the document.

“The current apprenticeship scheme (trailblazer and levy) is widely thought of as not fit for purpose,” it says. “We are in desperate need of a review of the apprenticeship levy, its objectives and use if we are to retain its credibility and legitimacy in the eyes of those who pay it. It needs to meet the needs of sectors and the transition of our economy, as well as companies of various sizes and requirements.

“A sectoral approach must be introduced with the introduction of sector-wide skills councils and a new National Skills Task Group to support new entrants, apprentices and the upskilling of the existing workforce to ensure a ‘just transition’ of our industrial base.”

There are working examples to follow, such as the rail school set up in Birmingham to feed the hunger for trained engineers in the new HS2 rail connections.

Unite has called for the establishment of a National Council for Recovery, and Regional Development Councils to work collaboratively with government, industry and unions not only to rebuild from Covid-19 and repurpose for climate change, but also prepare our economy for the opportunities from Brexit.

“To avoid mass unemployment and the social, as well as human, devastation that will follow,” it says, “we have an opportunity to create a confident, long-term stable environment for jobs and business with sector deals and state guaranteed loans based on a clear understanding of the challenges they face.”

Focus on apprenticeships

To this end the union is advocating the creation of a jobs guarantee scheme and sector skills councils, overseen by a National Skills Task Group with emphasis on skills and knowledge retention, with apprenticeships to support our young and the upskilling of those already in work.

“Those entering the labour market today will drive to transform our economy, but only if we nurture and use the power and capital leverage of the state in a strategic way to develop an economy to support them,” it says.

The idea that the current apprenticeship arrangements are woefully insufficient is not new. Back in July 2014 an article in the Guardian on apprenticeships quoted a report from Dr Martin Allen and Professor Patrick Ainley from the University of Greenwich which said, damningly, that rather than helping to boost young people’s economic prospects, most apprenticeships are “low skilled” and "dead end”.

One of the major problems is that too many people are taking an apprenticeship at intermediate level – equivalent to GCSEs. According to Allen figures from the Skills Funding Agency showed that in 2012, 56 per cent of those on the programme were at intermediate level and provisional figures for the first half of the 2013-14 financial years showed it to be at 70 per cent.

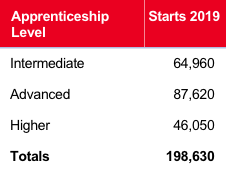

What is the situation now? The take up of apprenticeships in 2019 is given in the table, showing over 75 per cent are at the lower two levels, both equivalent to secondary school qualifications.

While it is good to get anybody on an apprenticeship the numbers show clearly that there are not enough. And the higher numbers at the lower skill levels indicate a lack of investment in Britain’s future workforce.

Meanwhile, the government is still stalling on investing in the adaptability of Britain’s manufacturing to switch to products the class require now amid the Covid-19 crisis. It is resisting pressure from Unite to identify domestically based firms to manufacture personal protective equipment (PPE).

But that pressure has resulted in the Motherwell-based Honeywell factory being contracted by the UK government to produce more than 70 million face masks for frontline workers, creating 450 jobs.

Unite has also held meetings with the government’s PPE and testing “tsar” Paul Deighton, providing him with the information regarding manufacturers capable of quickly switching to bulk production.

The real wealth of a country resides in the skills of its people, and the government needs to be constantly reminded that we are a nation which needs to produce in order to buy products that we cannot make.