Today’s world situation is similar to that of the pre-1914 years when imperialist forces were also intent on dividing up the spoils of the planet…

World War One scarred the twentieth century. It was colossally destructive of human life with an estimated death toll of over 16 million and inflicted millions of disabling injuries and devastating psychological traumas as well.

How can this violent eruption into general war be explained? Was there an underlying reason that caused this gigantic conflict? Or was it down to an unfortunate combination of unnecessary military adventures?

Certainly the cause of world war one was neither the assassination of an archduke in Sarajevo, nor the invasion of Belgium. These and similar explanations were no more than convenient excuses and trite pretexts to justify the ruling classes’ clamour for war and to obscure their real motives.

Economic shift

The real answers can be found in the sixty or more years preceding the outbreak of warfare in 1914. During this period all the great powers, both old and emerging, experienced a fundamental economic shift.

Great monopolies and giants in industry and finance had emerged; their predatory and conflicting interests and objectives were bound at some point to provoke wholesale war. Only the intervention of the peoples of the world to stop the momentum of the system of world capitalism could have prevented it. Unfortunately, nothing was forthcoming until the October Revolution in 1917.

'Capitalist economies outgrew free competition.’

From about 1860, the method of organisation of capitalism had changed drastically. The economies of the great powers outgrew and discarded free competition. Production became concentrated amid massive technological development and a remarkably rapid growth of industry in ever-larger enterprises.

That concentration led inexorably to the domination of monopoly enterprises over national economies. And the banks played a large part in this process, acting in a significantly different way from their earlier role of enabling trade and settling accounts.

As banking developed, it too became concentrated in a smaller number of establishments. Banks became supremely powerful monopolies controlling almost the whole of money capital as well as the larger part of the means of production and the sources of raw materials. Capital itself became the commodity to be traded – finance capital was born.

Monopolies

The sway of finance capital accelerated and intensified the trend for concentration of capital and the formation of monopolies. Inside each great power a few monopolists could and did subordinate the leading economic operations, both commercial and industrial, to their will.

Empires have existed throughout history. But with the transformation of capitalism into capitalist imperialism during between 1860 and 1914, a new type of empire was born. This beast aggressively combined class war against workers domestically with the oppression and exploitation of those in foreign lands. Over the years the word imperialism has tended to be used only and loosely in describing actions in foreign lands, whereas it should apply equally to the capitalist heartlands as well.

'Imperialism combined war against workers at home with exploitation of those abroad.’

What were the noticeable features of this new capitalist imperialism? Industrial production had become more concentrated and capital more monopolistic; these twin forces exerted a decisive dominant role over economic life.

Bank capital, once concentrated, merged with or subsumed industrial capital until oligarchies of finance capital were created. In marked contrast to the export of goods and commodities in earlier phases of capitalism, the export of capital across the world acquired exceptional importance.

These new international capitalist combines were impelled to either share the world between themselves, or to compete as rivals for mastery. Inevitably, their growth generated a bitter rivalry for the territorial division of the whole world between the biggest capitalist powers.

This headlong growth of imperialistic capitalism opened up an unsettled phase of increasing danger among the nations of Europe. It unleashed events and forces on the part of the competing forces that ultimately created the conditions for general warfare.

Domination

Five great powers dominated in Europe in the 100 years before 1914, namely Austria-Hungary, France, Germany, Great Britain and Russia. Elsewhere in the world, USA and Japan were up-and-coming great powers. Both had made startling industrial and financial developments in the decades immediately before 1914.

‘This heady mix of great powers provided the perfect ingredients…’

This heady mix of great powers – some well established, some new and rising, others relatively declining – provided the perfect ingredients for the outbreak of imperialist clashes in a world ripe for war.

The first major sign of imperialist jockeying was Prussia’s war against France in 1870. Led by Bismarck, Prussia annexed Alsace-Lorraine, which threw the French republic into the arms of Russia. Europe split into two opposing camps and began a period of military competition that triggered the Franco-Russian alliance and united Austria-Hungary with Germany.

The Prussian victory over France hastened German unification. And it also led to the Paris Commune, the first instance of workers holding power, albeit for a short period.

Worldwide

The leading great powers were not just contending with each other in Europe. They also competed across the world, exporting capital and expanding into non-capitalist countries.

By the 1880s the great powers had developed a strong tendency toward colonial aggrandisement. Inevitably wars broke out, some small, some larger.

Britain secured control of Egypt and created for itself, in South Africa, a powerful colonial empire. France took possession of Tunis in North Africa and Tonkin in East Asia.

Italy gained a foothold in Abyssinia. Russia accomplished its conquests in Central Asia and pushed forward into Manchuria. Recently unified Germany won its first colonies in Africa and in the South Sea.

Interference

The United States of America joined the imperial circle by the end of the century. It fought the decaying Spanish colonial empire for influence in the Caribbean and Pacific, procuring the Philippines for itself in eastern Asia. The US interfered in Cuba’s struggle for independence from Spain, effectively controlling that country until the 1959 revolution.

In Asia, the China-Japan War in 1895 resulted in Japanese territorial gains and initiated a chain of bloody wars. It also contributed to the Chinese nationalist revolution in 1910.

Britain formed a military alliance with Japan in 1902 to prevent other European powers gaining a foothold in the region and to hinder Russian expansionism.

Russia and Japan went to war in 1904 anyway. The unsuccessful 1905 Russian revolution followed after Japanese victory and then went through a period of domestic repression – a familiar pattern.

Antagonism

All these occurrences, blow upon blow, created new, extra-European antagonisms on all sides: between Italy and France in northern Africa, between France and Britain in Egypt, between Britain and Russia in central Asia, between Russia and Japan in eastern Asia, between Japan and Britain in China, between the United States and Japan in the Pacific Ocean.

It was clear, even at the time, that the underhand wars of each capitalist nation against every other, on the backs of Asiatic and African peoples, must eventually lead to a general reckoning. The wind sown in Africa and Asia would most likely return as a storm in Europe – where the great powers had concentrated increased armaments.

Foremost was the tussle for military dominance between Britain and Germany. In Germany, there was jealousy of Britain’s colonial spread and a determination to exert greater global influence.

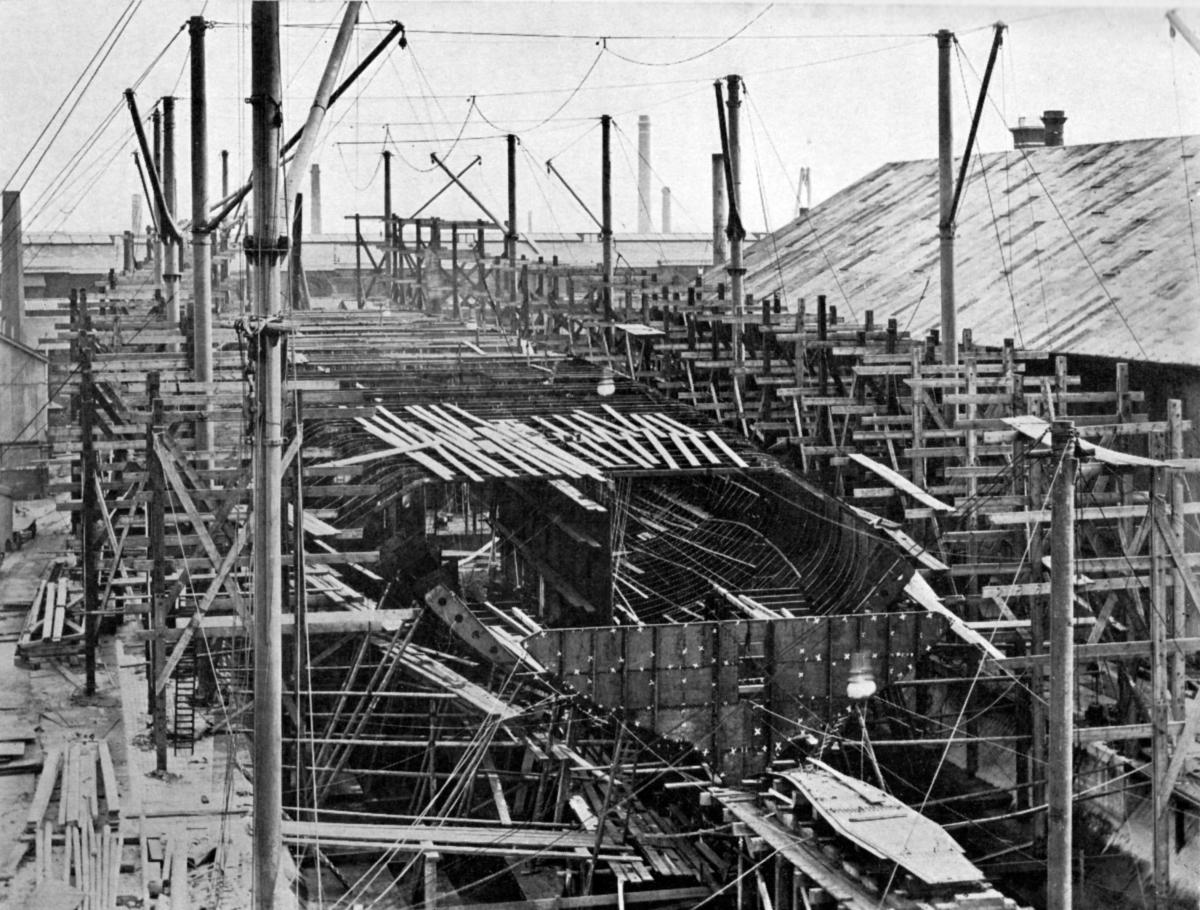

At the end of the 1890s the military and foreign policies of the German empire went through a radical upheaval. The German empire was changing from a purely land-based power to one with an equally powerful fleet.

A programme lasting almost two decades doubled German naval power, during which time it fought with Britain for supremacy on the ocean. This shift was not defensive, but marked an offensive stance in keeping with the aim of a greater Germany.

Undeclared war

In 1906 Britain launched HMS Dreadnought, a new class of battleship that rendered all other battleships obsolete because of its improved range, speed and firepower. This accelerated the naval arms race; Britain and Germany, the two greatest capitalist powers, were in an undeclared war.

By 1914 Europe was made up of armed camps after a series of international alliances. In such a tense situation, with Germany and Britain engaged in an escalating arms race, it was obvious that it would take very little to drive the nations of Europe, and eventually the world, to war.

The potential for war had in any case been overripe long before then. Rising military expenditure by the great powers were a direct preparation for war; for an inevitable final contest. War was constantly on the verge of breaking out.

Around Europe

As well as the wars of global expansion, political occurrences in and around Europe served only to bring conflict a step nearer – notably in the Balkans and other areas seeking independence from the declining Ottoman Empire.

In summer 1905, Germany made demands in the Morocco crisis, challenging Britain and France. In 1908 Britain, Russia and France threatened war over the fate of Macedonia, prevented only by the sudden outbreak of a revolution in Turkey.

In 1909 Russia mobilized in response to the annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina by Austria-Hungary. Germany then formally declared its readiness to go to war on the side of Austria.

In summer 1911 the German gunboat SMS Panther was sent to Agadir to oppose French attempts to regain economic dominance in Morocco. This would certainly have brought on war if Germany had not acquiesced and allowed itself to be compensated with French territory in the Congo.

'The source of the war was the economic and political antagonism of conflicting imperialisms.’

And in 1913 Germany, in view of the proposed Russian invasion of Albania, again threatened its readiness for warlike measures. The following year, during the July Crisis, all the European great powers went through a rapid spiral of threat and counter-threat until all were mobilized and ready for war.

The alliances and pacts before World War One were not the prime cause of the conflict, as some believe. Instead, the essential source of the war was the economic and political antagonism of conflicting rival imperialisms. Alliances were merely tactical devices by each imperial power to place itself in the best position against their competitors.

Upsurge

The early years of the twentieth century saw a massive upsurge in working class struggle in many countries as people combatted the domestic effects of imperialism. With the advent of world war, there was a terminal and immediate collapse in class struggle; workers started killing each other in warfare instead.

Rogue patriotism became the norm; this served the interests of finance capital and increased its spheres of influence. Workers – at least to start with – fell for the duplicity of engagement in “just wars”, which is an illusion.

No “just” war

There is nothing “just” about war. War is always an abomination and always the preserve of the ruling classes. When workers or peoples fight for social or national emancipation in revolutions or national liberation struggle, they are engaged in something far different from the degradations of war.

In the troubling world of today there are again rival imperialisms in unstable competition, just as there were in the pre-1914 years. If we don’t distance ourselves from them or if we don’t move to stop them, they will contrive to fashion another horror of war for their own exploitative ends but attempt to ruin us in the process.

We must pursue our own path.

- A shorter version, titled “What caused World War One?” appears in the July/August edition of Workers.