In a two-part analysis of class in the 21st century, Workers dismisses the notion that class is dead. The idea of class is central to making sense both out of our day-to-day experiences and of the world at large, and argues that action as a class can end the disastrous economic, political and social system of capitalism…

We begin with a simple snapshot of Britain and the world in the 21st century. Here, we find mounting problems of survival grow more severe for working people. In an effort to prolong itself, capitalism in decline turns on workers, its normal ploy. It bogs us down in a quagmire of problems, while those in control enjoy the fruits and maximise the spoils, relying on the opposition being distracted by crises.

Growing impoverishment and oppression is reserved for workers in or out of work. Gargantuan amounts of wealth are amassed by capitalists on a scale never witnessed before, particularly by finance capitalists, who prosper inside an economic depression that is entirely of their own making.

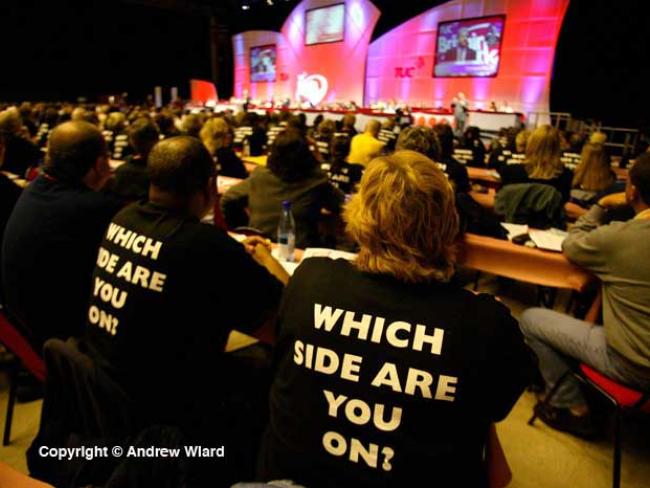

The smokescreen of “We’re in it together” is trotted out with repetitive hypocrisy – a whopping falsehood believed only by the gullible, certainly never entertained by aggrandising capitalists. The enemies of working people are actually very few, either in Britain or across the world – just tens of thousands – with an estimated 7 billion people in the world, most of whom are workers dependent on selling their labour power to survive. And yet it is the interests of the minority that dominate.

‘Some prefer to cling to illusions that they are middle class.’

How do we account for the recent loss of class identity and consciousness? In the 1970s – just a few decades ago – chatter was about “Who Rules Britain?” Nowadays, few commentators even bother with our class or credit it with any influence. Both of these attitudes are flawed, the first a gross over-inflation, the second a result of media fascination with wealth and glamour.

Among other factors, how our class interpreted and experienced the post-war decades is highly significant. Due to the military and political successes of the Soviet Union in the victory over fascism in the Second World War and working class advance elsewhere, the rulers could not rule in the old way and were forced to run society with full employment, a free National Health and education service that went against the grain of capitalism. Instead of keeping to the traditional culture of our class, complacency set in. When the assault of the ruling class was renewed from about 1970, our class was not in the best state of health to respond.

Although there are only two classes in Britain, not everyone in the working class admits (or welcomes) their class position. Some prefer to cling to illusions that they are middle class or superior professionals or special individuals distanced and apart from a working class even though the vast majority are only a salary payment away from difficulty and a few payments away from destitution. These illusions lessen people’s willingness to organise collectively yet surely making or growing things or providing essential services or culture – real value creation – is better than being an investment banker or a hedge fund manager who produces nothing for the betterment of society as a whole.

Clarifying class

Class is not decided subjectively but determined by your relation to the means of production. Either you own them as a capitalist, or you do not – and have to sell your labour power to those that do.

If you seek a perceptive theory of class, then you have to explore the writings of Marx, as he is far-and-away the pre-eminent thinker on the matter. We can admire the prescient sweep of these two observations in the Communist Manifesto written in the 19th century:

“Our epoch, the epoch of the bourgeoisie, possesses, however, this distinct feature: it has simplified class antagonisms. Society as a whole is more and more splitting up into two great hostile camps, into two great classes directly facing each other – bourgeoisie and proletariat.”

and:

“The bourgeoisie has stripped of its halo every occupation hitherto honoured and looked up to with reverent awe. It has converted the physician, the lawyer, the priest, the poet, the man of science, into its paid wage-labourers.”

Growth of working class

Over the last 300 to 400 years there has been a stupendous growth in the size of the working class, as capitalism has gradually spread over most of the world. Marx’s observation in 1848 that the world was splitting more and more into two classes was very prophetic. While others perceived only mutually exclusive social groups, he discerned a vital trend and projected its potential.

A transformative process that started in Britain with the Industrial Revolution of the 18th and 19th centuries has fanned out almost everywhere.

Where Britain led, others have followed. The world’s peasantry are fast disappearing, as more and more of agriculture is run along capitalist lines. In terms of size the working class of the world is now the predominant class, set in future decades to grow globally even bigger. A wholesale shift of population from living in overwhelmingly rural societies to urban, wage-earning ones has occurred throughout the world. Inexorably, the trend continues.

A class for itself

Though the working class of the world grows in leaps and bounds, so far there is perplexingly little sign in recent decades of corresponding ideological development to accompany the numerical growth. There has even been a noticeable lessening, or even collapse, of working class consciousness in recent decades; not just in Britain but elsewhere. If the world is to be saved from the misrule of capitalism, this worrying withdrawal from organisation and identity has to be confronted and reversed.

While a reactionary class operates across the world according to similar strategies and is conscious of its class interests, our revolutionary class does not act yet as a class-for-itself, conscious of its destiny. In Britain and the world, there is a glaring disparity between our limitless potential and the crippling, self-imposed limitations of our current thinking.

Why then are workers so reluctant to bury capitalism, which ought by now to be as faded a relic as rule by landed aristocracy? Why do we tolerate such an outmoded, anachronistic, anti-democratic system? If the ruling classes of the world and of Britain are clear about their class and strategic interests, why can’t workers in Britain and elsewhere be clear too? If the rulers, who have to overcome innate competition, can identify and act on their essential interests, why can’t we? As a conundrum it’s easily stated, but lack of a solution so far to this quandary remains the fundamental stumbling block that curbs humanity’s progress.

• Can conclusions be drawn from our development as a working class? Are there pitfalls to avoid and advantages to maintain within our chequered past? In the September issue of Workers, in the second part of this analysis of class in the 21st century, we study how the promise and despair of the rich experience of the first working class can help chart our way out of absolute decline.