18 March 2019

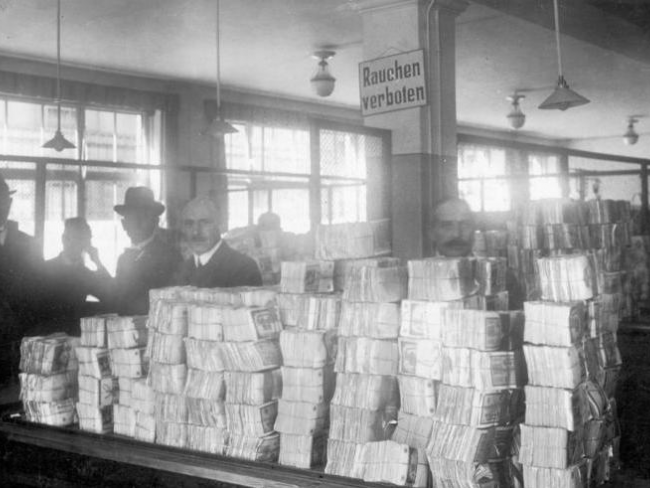

Piles of new banknotes awaiting distribution at the Reichsbank, during the hyperinflation of nearly a century ago. Photo Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-R1215-506 (CC-BY-SA 3.0).

Leaving the EU is about politics first and foremost. But with a global economic slump coming, it makes economic sense too.

The push to leave the EU by all available means is not driven by a desire for short-term economic gains. Political independence is the goal. But Brexit is coinciding with the reappearance of a global economic slump.

British workers want to leave the EU because they see that the EU emperor has no clothes. The June 2016 referendum result was entirely rational. It represented a sophisticated view of the connection between economics and politics and won’t be swayed by false threats of economic gloom.

But it is important to recognise what’s happening in the world economy and to differentiate between slump and Brexit, despite the claims of pro-EU propagandists.

False

An example of an attempt to create a false image was the reaction to the recent Honda UK factory closure announcement. The reason for that decision was Honda’s worldwide overproduction of cars, as was the decision by Nissan to cut back production at its Sunderland plant.

Yet media and politicians tried to attribute this solely to Brexit with comments such as “when Honda says they will close their plant you would expect that more people would voice their concerns regarding Brexit.”

Honda announced at the same time that its European HQ would stay in the EU: “Honda’s European HQ will continue to be located in Bracknell in the UK. It will be focused on serving the needs of its European customers.”

But there is a connection that does link slump to Brexit. The desire for an independent Britain started to intensify from 2007 onwards. This was at the beginning of capitalism’s financial collapse. This prompted the majority of the British populace to want to uncouple Britain from the EU’s ongoing failure.

New recession

Globalist reactionaries, the EU among them, have no meaningful political narrative because the problems of the 2007-2009 financial collapse will not go away. According to a survey released at the beginning of March three-quarters of the members of the US National Association of Business Economics felt a new recession will occur no later than 2021.

‘The worldwide financial edifice shows the weaknesses apparent after 2007.’

The timing of a downturn is not a given, but there’s no avoiding the conclusion that capitalism is in a precarious state. Firm evidence was provided late last year. The US Federal Reserve (US Fed) again raised US base interest rates.

At the time it said that more rate increases were in the pipeline. On that news the worldwide financial edifice began to once more show all the weaknesses that were apparent during the years following 2007.

Fear

By early December 2018 equity and bond prices had started to collapse by ten per cent or more. Financial markets feared that all central banks, not just the US Fed, were about to significantly reverse quantitative easing, the attempt to manage a way out of the crisis by injecting money into the financial system. But it stores up problems which emerge later on.

The markets fear that central banks will not only reduce the level of QE, but will also significantly reduce credit. This fear was already beginning to emerge in September 2018 when the EU’s European Central Bank (ECB) said that its own quantitative easing programme would stop by the end of 2018.

At the beginning of this year the US Fed announced it was putting future anticipated interest rate rises on hold. That was completely opposite to its declared intention a month earlier. Shortly afterwards the ECB announced a similar about-turn in its own monetary policy. Both US Fed and ECB were concerned about negative German industrial data and other economic indicators pointing the same way.

“Pervasive uncertainty”

Outgoing ECB president Mario Draghi admitted on 7 March this year that central banks cannot solve the underlying problem of “pervasive uncertainty”. This has left EU policymakers groping in the dark. But December’s turmoil can be seen as a dress rehearsal of what is to come.

Nowhere were the worldwide economic concerns in December more evident than in the EU. It emerged over Christmas that banks across the Eurozone had alarmingly high financing costs. Massive operational weaknesses became apparent.

For example, Germany’s Deutsche Bank had to pay heavily for its funding requirements. The Italian bank Uni Credit was in the same boat. It was forced to pay over 8 per cent a year in return for a loan of £3.5 billion to keep it afloat. Elsewhere Spain’s Santander Bank announced that it was altering its debt repayment schedule and so avoid repaying on time the debt owed on one of its bonds.

Analysts from Union Bank of Switzerland have since forecast that 450 billion euros of banking debt instruments need to be issued in the next twelve months. This has forced the ECB to make a new offer of cheap loans to those banks (that is, printing money). That’s the exact opposite to its declaration in September last year.

‘Private capital markets are not prepared to finance the solvency of Eurozone banks.’

The conclusion from all of this is that private capital markets are not prepared to finance the solvency of Eurozone banks. As in 2007-2010 and 2013-2014 there is insufficient investor demand.

Quantitative easing must eventually end, to avoid a repeat of a type of 1920s Weimar Republic financial collapse and hyperinflation. When it does stop, the indications are that euro bank funding costs will rise to unsustainable levels – a repeat of the credit crunch ten years ago.

In short, the EU is between a rock and a hard place.