The publication on 11 January of the government’s plan to manufacture and deliver Covid-19 vaccine shows vividly how much work and ingenuity have been applied to innovating our way out of the pandemic that has brought much of the world to a halt.

The government, in its typical style, glosses over its complacency, deafness to warnings and lack of investment before the pandemic struck. Yet that makes the progress since then all the more remarkable.

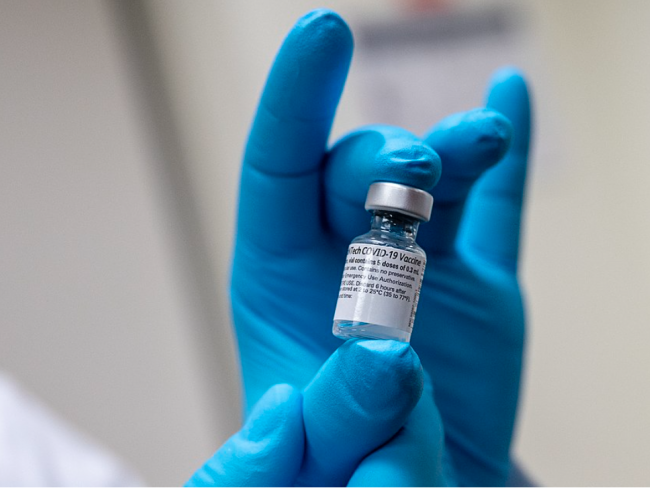

A comprehensive vaccine rollout is under way here, spearheaded by the Pfizer/BioNTech and AstraZeneca vaccines. A third vaccine, made by the US company Moderna using technology similar to the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine, was approved for emergency use in Britain on 8 January.

And several more vaccines are on the horizon. The first one likely to be deployed in Britain comes from the US conglomerate Johnson & Johnson, which has developed a vaccine using similar technology to Oxford/AstraZeneca. Sir John Bell, Regius Professor of Surgery at Oxford, is working alongside its pharmaceutical arm, Janssen, based in Belgium.

Forefront

Last year the government went all out to order millions of vaccine doses well in advance of regulatory approval. It’s a strategy that – combined with the existence of the NHS – has put Britain at the front of the global vaccination curve. And it shows what can be achieved with planning and determination, rather than the laissez-faire of capitalism and its “free” market.

For example, Britain has already ordered 30 million doses from Janssen with an option to buy 20 million more. The UK regulator, the Medicines & Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), is expected to authorise the product for emergency use early in February. This means it could become available for use by mid-February if all goes well. It can be stored and transported at standard refrigeration temperatures.

With the Janssen and Oxford vaccines, a genetic instruction for building antibodies to Covid-19 is inserted into a weakened version of a virus that causes common colds in chimpanzees. This adenovirus penetrates the patient’s cellular DNA and is copied onto messenger RNA (mRNA). When this harmless form is released into the blood stream, the so-called "spike protein" attached to it triggers an immune response.

With these vaccines the recipient cell itself generates the mRNA inclusive of the spike protein. In the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine, mRNA with the spike protein already attached is generated not by the human body, but in the laboratory as part of the manufacturing process in advance of injection into people.

Spikes

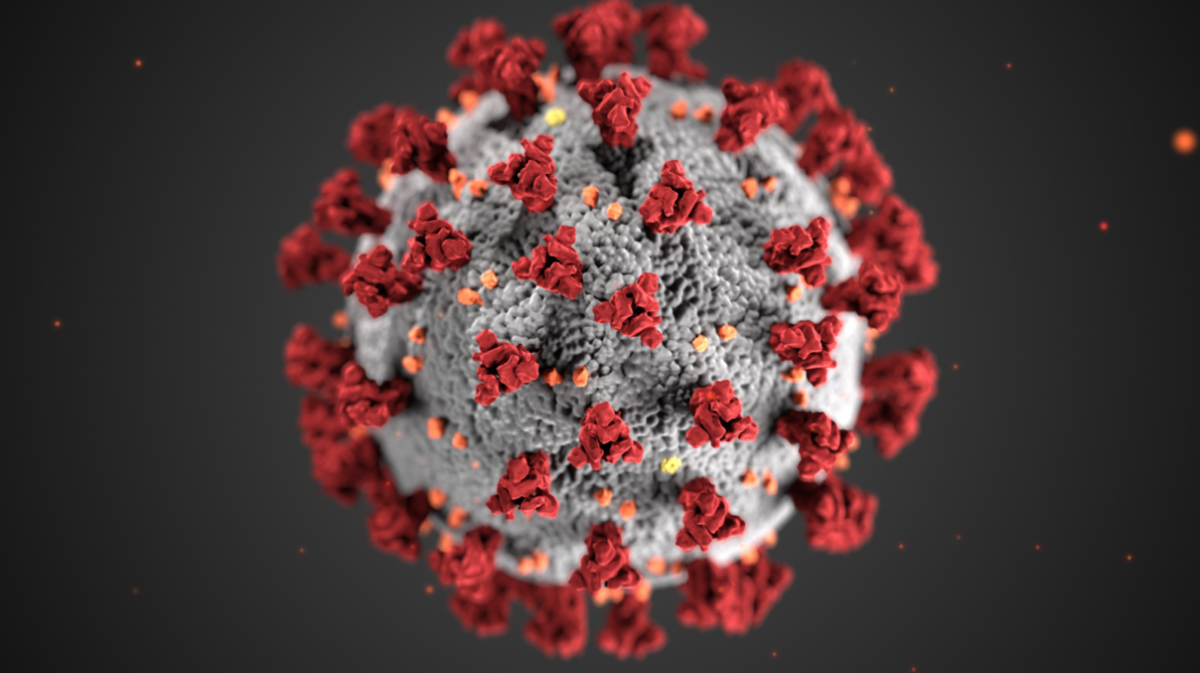

The spikes are the key. The Covid-19 spike proteins sit on an array of spikes that cover the surface of the virus, so much so that when the virus is viewed under a high-power microscope it seems to form a halo, or corona, around it – hence the name coronavirus.

These spikes are crucial to the ability of the virus to infect and reproduce. Once the virus is inside the body, the spikes attach themselves to receptors on the surface of our cells and con them into absorbing the virus inside them.

Viruses cannot replicate on their own, but once inside, the virus can turn the infected cell into a kind of factory. It uses viral RNA as a template to create even more virus – amplifying the infection.

The Pfizer/BioNTech technology is novel and highly innovative, and is the first of its kind. The vaccine is temperature-sensitive and relatively expensive to make. But it is highly effective and deployable even though storage and transportation are problematic. And these issues might be overcome by changes in formulation at some future date.

Advance

Deployment of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine in Britain represents a major advance. The similar product from the US company Moderna recently approved by the MHRA for emergency use is more temperature stable, but may still require freezing during transportation. The UK has 10 million doses on order and options on a further 17 million. However, the Moderna product is not likely to be available until early spring.

Imperial College, London has UK government and donor funding to produce an mRNA vaccine, and began clinical trials in June last year. If the vaccine is effective and safe, it promises significant benefits in deployment – especially in warm climates – as it is said to remain stable at temperatures of up to 40 ºC, rather than requiring freezing down to -80 ºC like the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine. But results of clinical trials are still awaited.

‘Oxford acted as soon as the Covid-19 genetic sequence was published.’

The “adenovirus” route used for the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine is based on an established technology, easy to reproduce and modify. The Jenner Unit at Oxford had already developed a vaccine against MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome) that is currently in clinical trials in Saudi Arabia. This enabled it to act quickly as soon as the Covid-19 genetic sequence was published online by Chinese researchers in January last year.

AstraZeneca is responsible for process development, manufacture and worldwide distribution. It is a large pharma company, but not a major player in vaccines at a global level. The top four in the world are GSK (UK-based), Merck (US, though last August it unveiled plans to create a £1 billion research hub in London), Sanofi (French, struggling to originate a vaccine of its own) and Pfizer (US). Together these four companies had a combined capacity to produce 4.9 billion doses of vaccines at the time of the swine flu pandemic of 2009 to 2010, capable of being ramped-up, even back then, to 6.5 billion at marginal cost.

Collaboration

The Oxford/AstraZeneca collaboration is supported by the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, UK Research and Innovation, the Department of Health and Social Care, the National Institute for Health Research, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, and others.

Its vaccine is produced at three sites; Oxford Biomedica, Cobra Biologics (Staffordshire), and Helix, whose main factory is in the Netherlands. Tissue taken from human kidneys, called producer-cells and often referred to as “mini-factories”, have Covid-19 spike proteins transferred into them forming a bio-reactive growth medium. Once this cell-culture reaches the right concentration for vaccination it is filtered and purified ready for eventual packaging.

Packaging – known as “fill-and-finish” – takes place in Wrexham at a site run by Wockhardt, a subsidiary of a large Indian pharmaceutical company producing “generic” (off-patent) medicines. Here the purified cell-culture is transferred into individual glass vials.

Rigorous

Approval for use in patients necessitates rigorous safety checks, which are done at the National Institute for Biological Standards and Control, whose main laboratory is in South Mimms, Hertfordshire. The vaccine is licensed, at present, only for emergency and not general use, so each new batch requires individual certification.

Public Health England’s ImmForm arm organises logistics and transportation, now in collaboration with the Army. Storage is in a normal refrigerator – this vaccine should not be frozen. Unopened, the Oxford vaccine can be kept as long as is necessary. Once opened it should be used within six hours. Each vial contains 8 to10 doses of a near colourless, slightly brown liquid. The second dose should be given at an interval of 28 days to 12 weeks.

The largest full-scale clinical trial to be launched in Britain so far is being conducted by Novavax (US) on its vaccine,. This is another good example of a new and rapidly emerging technology. Its candidate uses a genetically engineered sub-microscopic fragment of spike protein combined with an added component (an “adjuvant” known as Matrix-M) that can boost the immune response. Interim results from this study are expected during the first quarter of 2021. If it works well, we could see it here: the UK has 60 million doses on order.