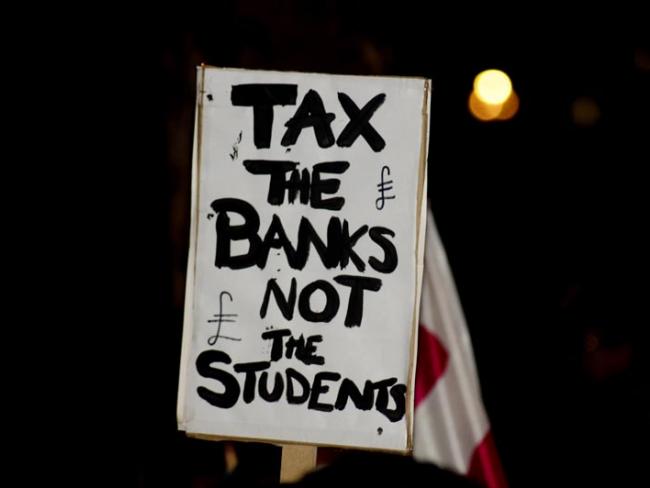

Still valid: a slogan from the 2010 protests against student fees. Photo Chris Harvey/shutterstock.com.

Students pay heavily for their loans. But overpaid university administrators are still demanding huge fee rises. Meanwhile overseas students are taking places which should go to people raised here…

Policy makers say that a degree is an asset. But it is one that students pay dearly for. Squeezed between government penny-pinching and universities’ determination to boost income which enables ludicrously high salaries for many vice-chancellors and senior administrators, they are finding that a degree costs them a lifetime of debt.

That is, if they are lucky enough to find a university place at all. Thousands are set to miss out on a university place this year, partly due to a change in marking. But there is another, underlying reason: universities prefer foreign students.

An investigation by the Sunday Times published at the beginning of August showed that over half the Russell Group universities reduced their tally of British undergraduates from 2008 to 2016 (the most recent year for which figures are available).

Universities outside the Russell Group also took an axe to British applicants. Lancaster reduced the number of British undergraduates by 17 per cent while more than doubling the number of overseas students.

Cynical

It’s no secret why this is happening: overseas students can pay up to four times the fees charged to British applicants. Cynically, some vice-chancellors are now pushing for fees for domestic students to rise to £14,000 or more to be closer to those of overseas students.

In Scotland the squeeze on applicants domiciled there is severe, and worsening, according to a report published in August by the group Reform Scotland.

Scottish students studying in Scotland do not have to pay fees, so the system is subsidised by large fees paid by English, Welsh, Northern Irish and overseas students. The result is a vicious cap on students from Scotland. According to the report, in the past 15 years there has been a 56 per cent rise in the number of Scottish school pupils applying for Scottish universities, but an 84 per cent increase in the numbers refused entry.

The Sutton Trust found in 2016 that Britain’s students borrow more than their American counterparts despite US degrees taking four years. This is likely to be because of high interest rates and flat wages, which have left graduates accruing interest on their debt without paying a substantial amount back. And as an article in the Times newspaper added when reviewing the situation this June, “the average loan balance has only increased since then.”

In total, 5.6 million graduates and students have outstanding loan balances with the Student Loans Company. The national total student debt is valued at £161 billion. Someone who graduated in 2021 earning £30,000 will repay £244 over the next year while accruing £976 in interest!

The majority of graduates with Plan 2 student loans — those taken out after fees were raised to £9,000 a year from 2012 — will never pay off their loan and instead will make repayments for 30 years until the debt is forgiven. Fees are currently capped for British students at £9,250.

The government changed the basis of student loan repayments at the end of February this year. The Institute for Fiscal Studies has calculated that the changes will help higher-paid graduates, but also that those on middling incomes will now find themselves repaying £20,000 more over a lifetime.

RPI inflation

From now on, interest will vary according to RPI inflation and graduate earnings. The move to RPI inflation – which the government refuses to use for pensions or pay settlements – alone will save the government a fortune while costing students dear.

Another big change is that new student debt will no longer be wiped clear 30 years after graduation. The Institute reckons that more than 70 per cent of today’s undergraduates can expect to have to pay off their loans in full, with no write-offs.

One student has a balance with the Student Loans Company for £175,830, the biggest outstanding debt held by any graduate. Another has £169,070 of debt and there are 29 graduates with loan balances of more than £150,000.

The National Union of Students (NUS) president Larissa Kennedy responded to the Institute’s research by saying: “We’re in a student cost of living crisis, which is pushing us to the brink.

“We’re hearing from students who are working three jobs to make ends meet, who can’t even afford to travel to their university library, and who are cutting back on cooking due to spiralling energy costs.

“Our research is showing that thousands more are relying on buy now, pay later loans from companies like Klarna.”

“We’re hearing from students who are working three jobs to make ends meet, who can’t afford to travel to their university library…”

Kennedy added, “Students are not cash cows.” But of course to the universities and the government cash cows (not to mention an army of slum landlords) is precisely what students are, and have been since a Labour government introduced tuition fees in 1998 and then began the process – continued by successive governments – of privatising the loan book.The last time this took was place in 2018, by then chancellor George Osborne, when a big tranche of loans was sold to the Deutsche Bank of Germany.

That privatisation process was halted by an announcement in the 2020 budget – a decision prompted by a change in Office for National Statistics accounting which meant, basically, that it would now treat the outstanding loans as debt rather than hiding them away.

In 2015, graduates’ finances went from bad to worse when the government changed the terms of student loans. The Cameron administration backtracked on promises that the minimum threshold at which graduates were asked to start repaying debt would be linked to average earnings in Britain. Instead it froze the threshold at £21,000 for the next five years.

This meant that debt repayments would begin much earlier than previously expected, and the amount borrowers have to pay back in each instalment would be higher.

Meanwhile, the cap on tuition fees had been rising relentlessly (and predictably) since they were introduced in 1998. In 2016, the government announced plans to increase tuition fees from £9,000 to £9,250, where they remain today.

It’s no surprise that over half of those with a student loan or a bursary do not believe it covers the costs of living.

“Just one in four students don’t hold a job alongside their studies,” the NUS reported in March this year. Even so, it said, “79 per cent of students are worried about their ability to get by financially. One in four have less than £50 a month to live off after rent and energy bills, and 5 per cent of students are visiting food banks.”

No wonder the NUS is arguing that the Treasury must introduce a maintenance support system which will allow all learners to live in comfort and security while studying in further and higher education. It also wants to see rent protections for students – average rents have risen 61 per cent in the past decade – and a reversal of planned cuts to the student loan repayment threshold.

Heating or eating

When you hear that students can’t afford to travel to their campus library, you know there is something deeply wrong. Thousands of students are already being forced to choose between heating and eating, and with this cost-of-living crisis it can only get worse.

The government needs to act, and the people must speak out. It is time to stop applying sticking plasters on the current marketised system – the profit-driven model is broken.

Britain needs a properly educated and highly skilled workforce. There needs to be a new vision for education, one that is fully funded and accessible for all.